After being convinced by a series of favorable articles, I bought a few shares last month of the EWY fund, which holds shares of major South Korean companies. The narrative seemed compelling: the vast production of compute processing chips for AI has led to a structural supply shortage of fast memory chips. South Korean firms excel in making these chips, and so high, growing profits seemed assured. What could possibly go wrong?

What I didn’t know was that thousands of other retail investors were thinking the exact same thing, and hence had bid the price of EWY up to possibly unreasonable levels. Somehow, my bullish analysts missed that point. In particular, the South Korean market is driven by an unusually high level of margin trading, where investors borrow money on margin to buy shares. A market drop leads to margin calls, which leads to forced selling, which really crashes prices.

The other thing I did not know was that, two days after my purchase, the attacks on Iran would commence. Oops. Among other things, this would drive up the world price of oil, which impacts energy importers like South Korea. This seems to have been the trigger for the sharp stock drop.

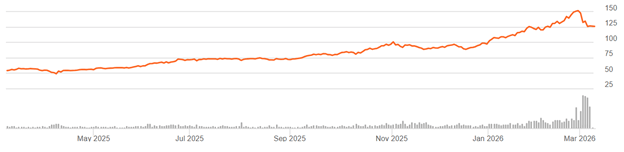

Here is the six-month price chart for EWY:

As it happened, I bought pretty much at the top, and as of Monday midday when I am writing this, EWY was down about 17%. That doesn’t look like much of a drop on the chart, because of the long run-up to this point, but it is an unpleasant development if you just bought in two weeks ago.

Fortunately, when I bought the EWY shares, I set up a protective options collar, since this was not a high conviction buy. First, I bought a put with a strike price about 7% below my purchase price, which would limit my maximum loss on the EWY shares to 7%. A problem is that this put cost serious money (about 11% of the share price), so my maximum loss could actually be 7% plus 11% = 18%. Therefore, I offset nearly all the cost of the put by selling a call with a strike price about 17% above the current EWY share price. That meant that I could profit from a rise in EWY share price by up to 17%, while being protected against a drop of more than 7%. That seemed like a favorable asymmetry (7% max loss vs 17% max gain).

This arrangement (buying a protective put to limit downside, financed by selling a call which limits upside) is called an options “collar”. I’d rather accept a limited upside than have to worry about doing clever trading to mitigate a big loss.

As of Monday, my collar was working well to protect the overall position. As might be expected, the value of my put increased, with the drop in EWY share price. But also, the value of my call decreased, which further helps me, since I am short that call. The net result was that about 75% of the loss in the stock price was compensated by the changes in values of the two options.

This is just a small, experimental position, but it was nice to see practical outcomes line up with theory.

Disclaimer: As usual, nothing here should be considered advice to buy or sell any security.