I pick up from my previous post in May 2020.

That tweet from early May captures some of the joys and frustrations of working from home with small children. It was hard to get work done. My career suffered. At the same time, in my case, there were happy moments. My kids got more time with me and also with each other. One reason I didn’t go crazy is that we could get outside and the weather was decent throughout “lockdown”.

Something that happened quietly is that two-income parents hired private nannies and never mentioned it on social media. I know there are lots of families who did not do that and had a hellish year trying to parent while working from home. In my case, daycare was back open in June with extra health precautions.

Late Spring was a time when it seemed like the United States might be the worst-performing country. Certain parts of Asia were models of efficiency and cooperation, by comparison.

July 2020 – My public school system (which had gone virtual in the Spring) announced that elementary parents would have a choice of in-person (with masks) or virtual for the Fall. Our schools have been open all year (with masks) and no major outbreaks.

High school and middle school students did more forced remote days than elementary-aged kids. I really appreciated the creativity and flexibility. Remote school is harder on younger kids (and parents of younger kids).

I emailed my city representative to ask for a drive-through testing site in our city. He said he would bring it up at the council meeting that night. Within two weeks, they had done it! This was incredible. I did not expect that because of one request this would suddenly just happen. I suppose there were enough people who wanted it already. It probably helped that city council elections were right around the corner and he could take credit for doing something helpful. Twice in 2020, I used my city hotline to get an appointment for a Covid test.

In August, my university got ready to bring students back for some in-person classes, while also offering remote options for every class. The campus sprouted one-way walking stickers and masks were required everywhere.

Economists moved conferences online. On September 10, 2020 I stayed up a little late to catch one of my Chinese colleagues presenting at the ESA worldwide virtual conference. My daughter didn’t want to stay in bed, so I let her stare at the Zoom meeting for a bit.

I have said nothing so far about politics in 2020, the year of politics. The televised debate between President Trump and now-President Biden in September of 2020 was a stressful event for me. If we can’t even speak to each other, then no amount of good ideas will help us solve problems. That sad moment in American history made me more determined to maintain this blog as a place to talk about ideas.

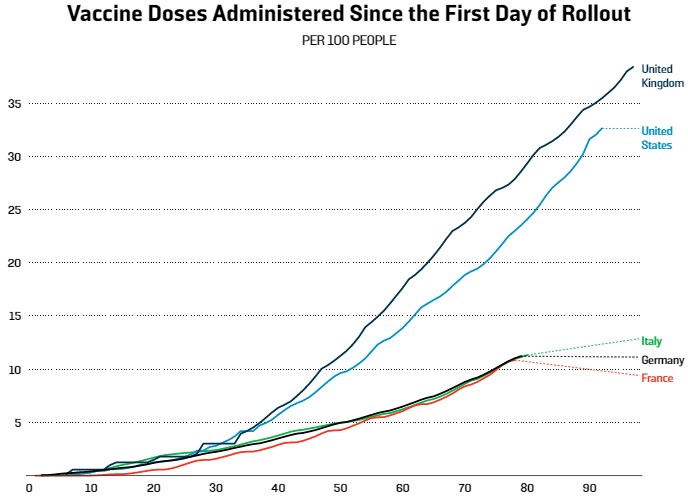

The Fall of 2020 was when intellectual soldiers like Alex Tabarrok were alerting us to the fact that we could have vaccines if the government would let us. I was following that news and doing some signal-boosting. Some of my friends on social media announced that they were participating in vaccine trials – thanks!

My university offered rapid tests to employees at the end of the Fall semester. It almost felt like a miracle to be able to just know in 15 minutes if I was carrying Covid or not (yes, I know about the false negatives).

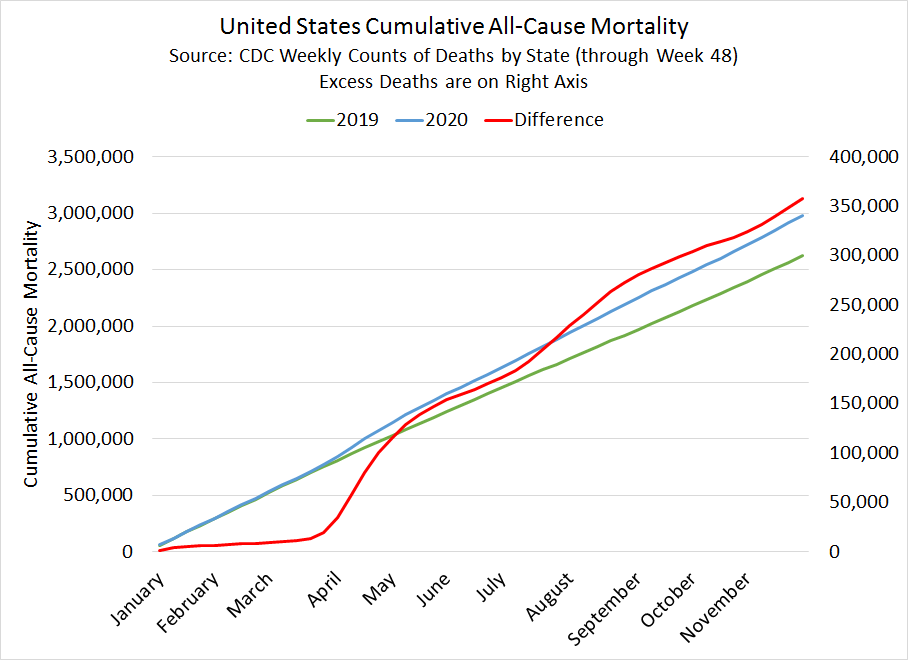

There were moments in peak-wave when local hospitals were full because of Covid. Alabama’s worst month as measured by deaths was January 2021. When Covid was spreading widely in December 2020, I believe a lot of people did not expect that vaccines would be available so soon in the future. On the margin, a few more people might have foregone holiday parties if they had known.

Vaccines became available to medical professionals around January 2021. That was exciting news, since we had all been feeling bad about the doctors and nurses treating infectious Covid patients.

Earlier than I expected, I was able to get the Pfizer vaccine because of my “educator” status in the state of Alabama. It is convenient that I live near UAB hospitals. They had the technology for cold storage and administering the Pfizer vaccine. It was a huge relief to get the vaccine while teaching in-person classes. Since I had been following vaccine news closely, it felt like a huge achievement.

There was a period of time when conversation among my neighbors and colleagues revolved around the vaccine. Water cooler talk was “which one did you get?” or “did you have side effects?” People told stories about how a friend called to tell them that one place had extra doses at the end of the day. Even when it was technically reserved for old people only, some young people found connections. One of my students told me he wouldn’t be in class because he was going to drive 6 hours to another state to get a vaccine. I don’t want to make the system sound corrupt, because it largely was not. It’s just a fact that some places couldn’t distribute all of their doses to the people who were designated for them. It was better to get the leftovers into arms than waste them.

I treasured that energy, and I miss it. Now, in May 2021, after all the work that went into producing vaccines, Americans are refusing to show up for shots.