I have a new working paper with Bart Wilson titled: “You Wouldn’t Steal a Car: Moral Intuition for Intellectual Property”

This quote from the introduction explains the title:

… in the early 2000s… the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) released an anti-piracy trailer shown before films that argued: (1) “You wouldn’t steal a car,” (2) pirating movies constitutes “stealing,” and (3) piracy is a crime. The very need for this campaign, and the ridicule it attracted, signals persistent disagreement over whether digital copying constitutes a moral violation.

The main idea:

In contemporary economies, “idea goods” comprise a substantial share of value. Our paper examines how norms evolve when individuals evaluate harm after the taking of nonrivalous resources such as digital files.

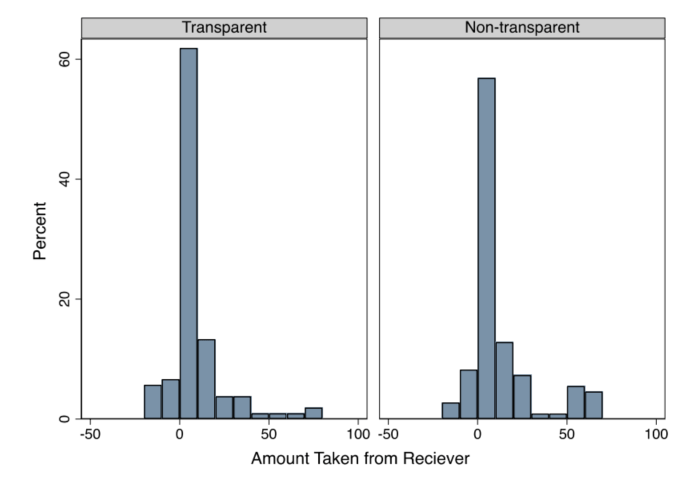

We report experimental evidence on moral evaluations of unauthorized appropriation, contingent on whether the good is rivalrous or nonrivalrous. In a virtual environment, participants produce and exchange two types of resources: nonrivalrous “discs,” replicable at zero marginal cost, and rivalrous “seeds,” which entail positive marginal cost and cannot be simultaneously possessed or consumed by multiple individuals. Certain treatments allow unauthorized taking, which permits observation of whether participants classify such actions as moral transgressions.

Participants consistently label the taking of rivalrous goods as “stealing,” whereas they do not apply the same term to the taking of nonrivalrous goods.

To test the moral intuition for taking ideas, we create an environment where people can take from each other and we study their freeform chat. The people in the game each control a round avatar in a virtual environment, as you can see in this screenshot below.

In the experiment, “seeds” represent a rivalrous resource, meaning they operate like most physical goods. If the playerin the picture (Almond) takes a seed from the Blue player, then Blue will be deprived of the seed, functionally the equivalent of one’s car being stolen.

Thus, it is natural for the players to call the taking of seeds “stealing,” Our research question is whether similar claims will emerge after the taking of non-rivalrous goods that we call “discs.”

The following quote from our paper indicates that the subjects do not label or conceptualize the taking of digital goods (discs) as “stealing.”

Participants discuss discs often enough to reveal how they conceptualize the resource. In many instances, they articulate the positive-sum logic of zero-marginal-cost copying. For example, … farmer Almond reasons, “ok so disks cant be stolen so everyone take copies,” explicitly rejecting the application of “stolen” to discs.

Participants never instruct one another to stop taking disc copies, yet they frequently urge others to stop taking seeds. The objection targets the taking away of rivalrous goods, not the act of copying per se. As farmer Almond explains in noSeedPR2, “cuz if u give a disc u still keep it,” emphasizing that artists can replicate discs at zero marginal cost.

We encourage you to read the manuscript if you are interested in the details of how we set up the environment. The conclusion is that it is not intuitive for people to view piracy as a crime.

This has implications for how the modern information economy will be structured. Consider “the subscription economy.” Increasingly, consumers pay recurring fees for ongoing access to products/services (like Netflix, Adobe software) instead of one-time purchases. Gen Z has been complaining on TikTok that they feel trapped with so many recurring payments and lack a sense of ownership.

In a recent interview on a talk show called The Stream, I speculated that part of the reason companies are moving to the subscription model is that they do not trust consumers with “ownership” of digital goods. People will share copies of songs and software, if given the opportunity, to the point where creators cannot monetize their work by selling the full rights to digital goods anymore.

A feature of our experimental design is that creators of discs get credit as the author of their creation even when it is being passed around without their explicit permission. Future work could explore what would happen if that were altered.

Related Reading

“An Experiment on Protecting Intellectual Property” (2014) with Bart Wilson. Experimental Economics, 17:4, 691-716.

“You Wouldn’t Steal a Car: Moral Intuition for Intellectual Property,” with Bart Wilson (SSRN)

Joy on The Subscription Economy (EWED)

The Anthropic Settlement: A $1.5 Billion Precedent for AI and Copyright (EconLog)