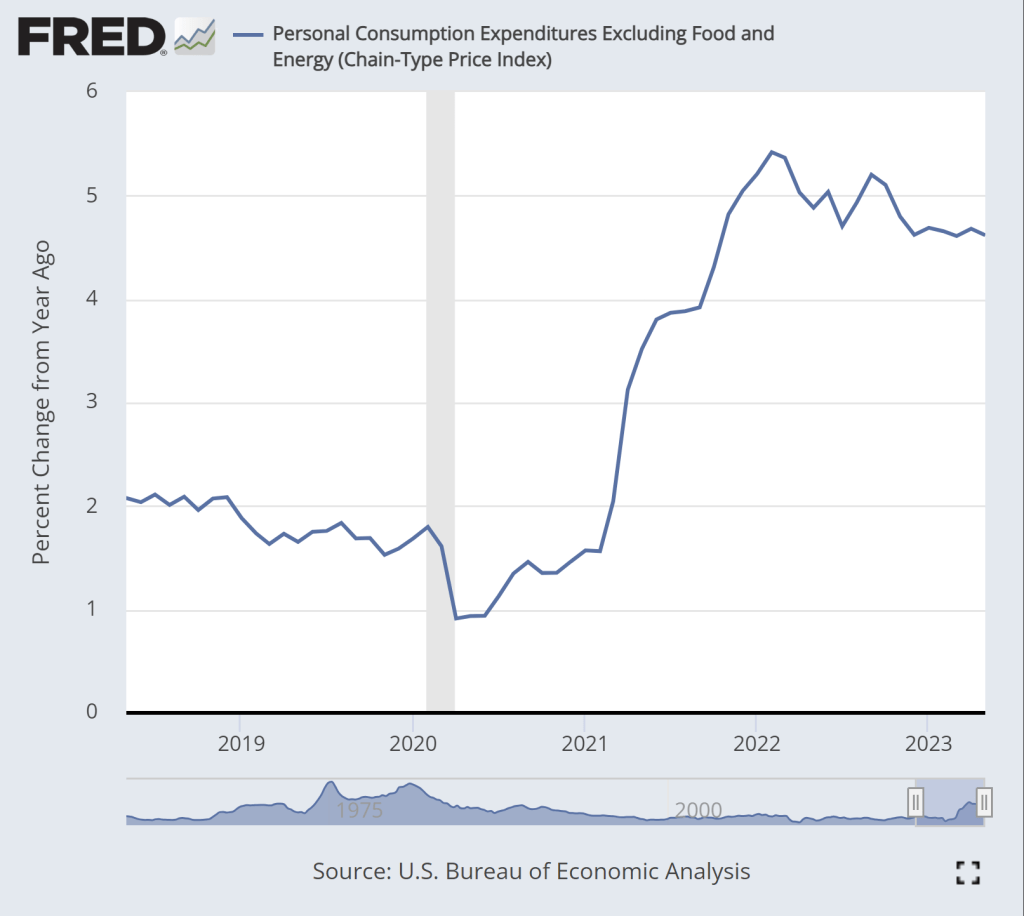

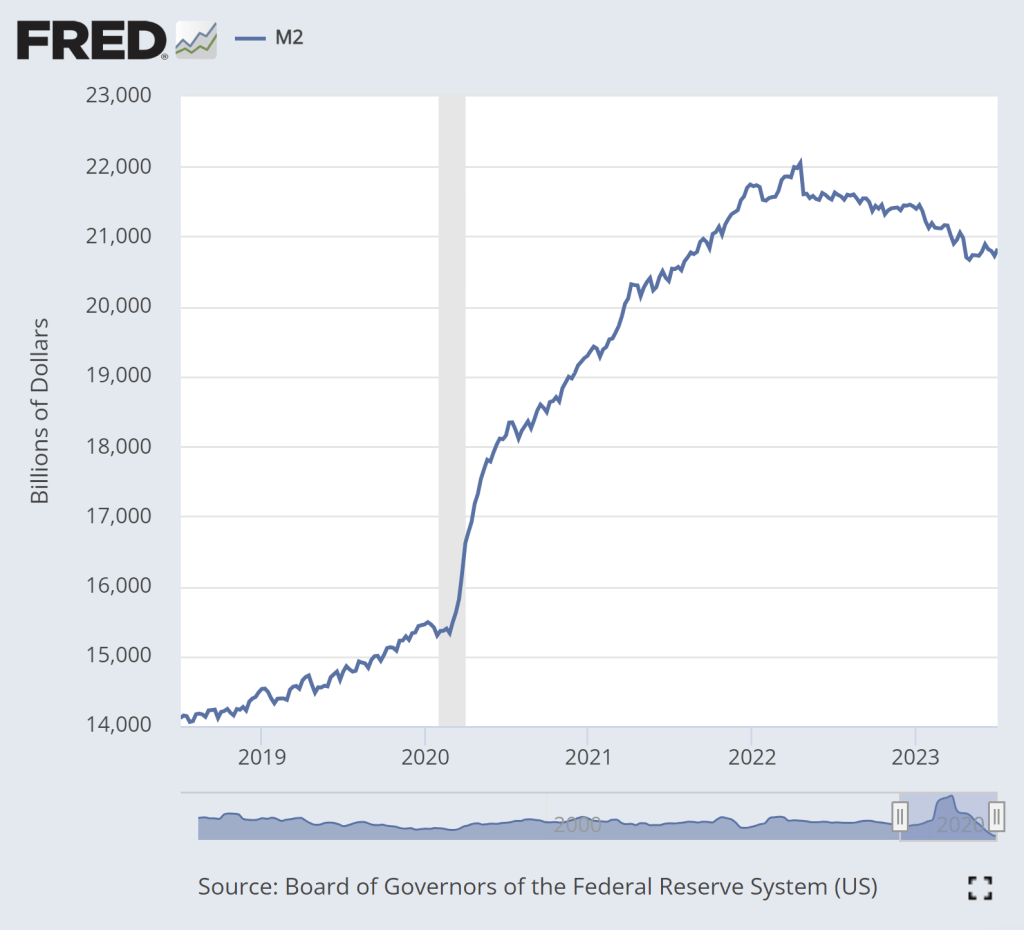

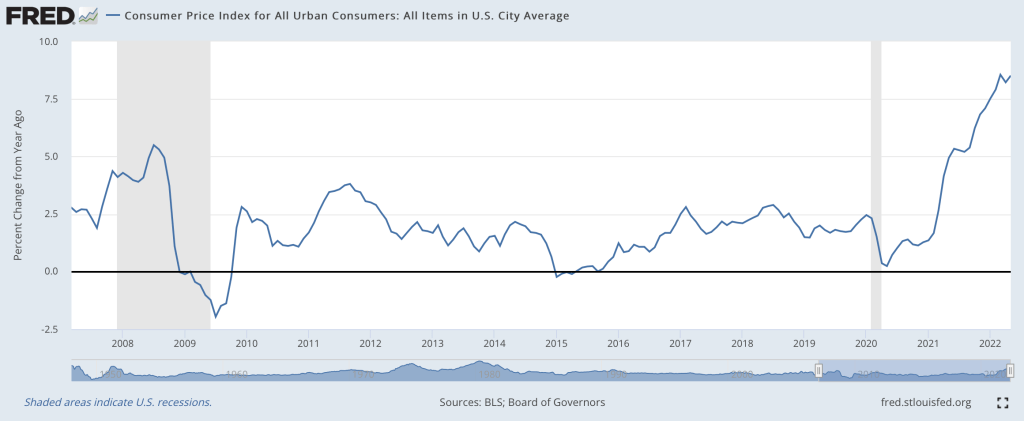

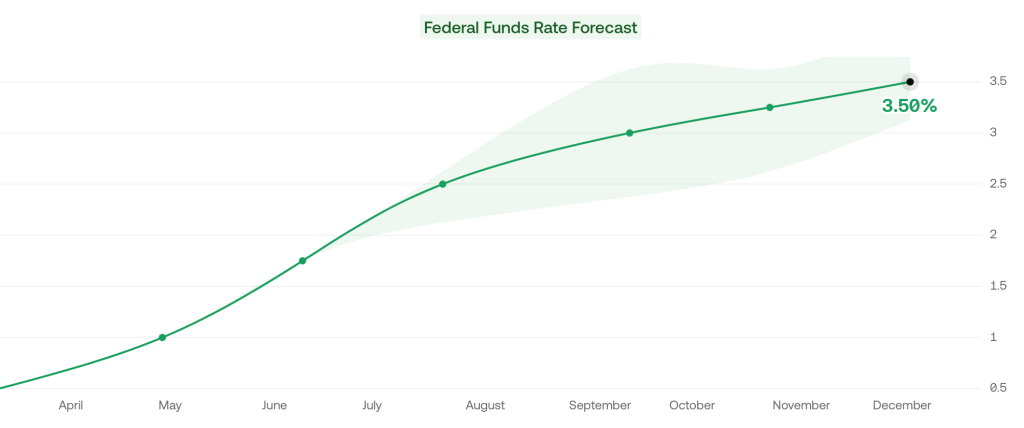

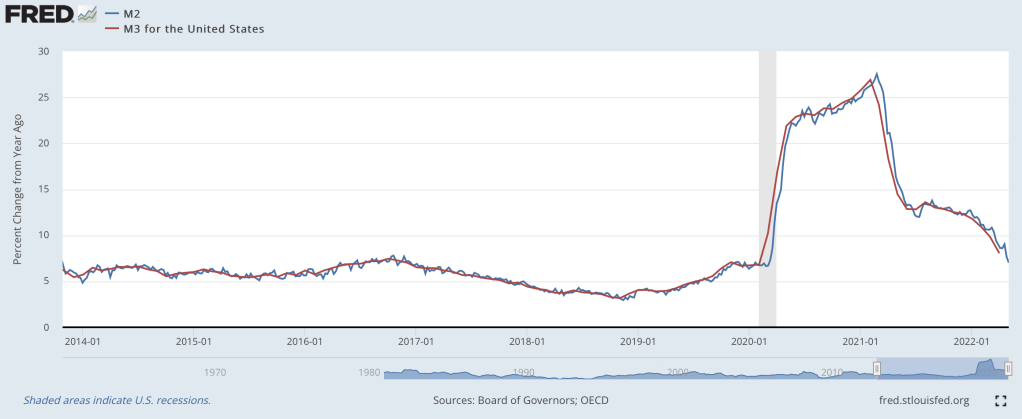

Money and interest rates have been in the news because the Fed wants to slow the rate of inflation, maintain financial stability, and avoid a recession. Let’s break it down. First, some broad context. The M1 and M2 were all chugging along prior to 2020. M2 was growing along with NGDP and, after raising interest rates, the Fed had begun lowering them again. Then Covid, the stimuli, and the redefinition of M1 happened. Now, we’re trying to get back to something that looks like normal. See the graphs below.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1aFgO

But these aggregates gloss over some relevant compositional changes. Let’s go one-by-one.

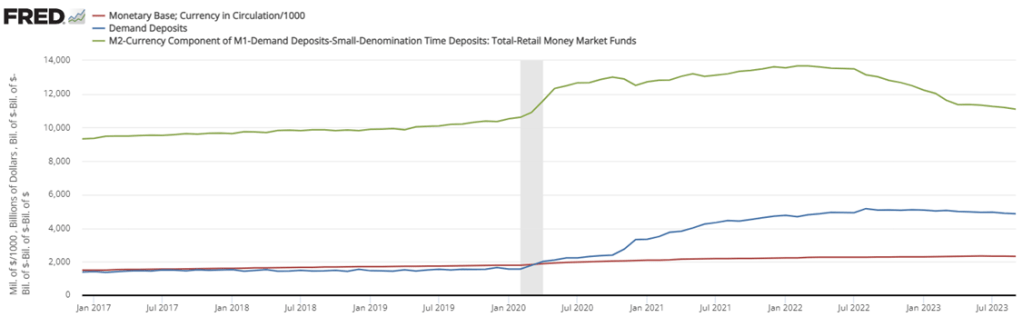

The monetary base includes both bank reserves and currency in circulation. We could break it down further, but I’ll save that for another time. What we see is that while currency in circulation did grow faster post-covid, it was nothing compared to the growing reserve balances. From January to May of 2020, currency grew by 7.5% while reserves almost doubled. That means a few things. 1) People weren’t running on banks. Covid was not a financial crises in the sense that people were withdrawing huge sums of cash. 2) Banks were well capitalized, safe, and stable. Further, uncertainty aside, banks were ready to lend. And they did. Not long after the recession, everyone and their brother was re-financing or taking on new debt. More recently, we can see that currency has stabilized and, again, most of the action has been in reserve balances. As of September 2023, reserve balances are down 23% from the high in September 2021.

The thing about the monetary base, however, is that reserves don’t translate into more spending unless the reserves are loaned out. The money supply that people can most easily spend, M1, is composed of currency held outside of banks, deposit balances, and “other liquid deposits” (green line below).* See the graph below. Again, most of the action wasn’t in the physical printing of hard, physical cash. People’s checking account balances ballooned thanks to less spending on in-person services and thanks to the stimulus checks and other relief programs. Deposit balances more than doubled from January to December of 2020. Ultimately, deposit balances were 3.3 *times* higher by August of 2022. Since then, the balances have been on a slow, steady decline of about 5.8% over the course of the year. But even then, it’s those “other” deposits, previously categorized as M2, where most of the action is. The value of those balances have fallen by a whopping 2.5 *trillion* and 19% dollars in the past 18 months. People are drawing down their savings.

Finally, we get to M2, the less liquid measure of the money supply. Besides the M1 components, it also includes small time deposits, such as CD’s, and money market funds (not including those held in IRA and Keogh accounts). Money market funds and small time deposits have *increased* in value since the post stimulus tightening as people chase the allure of higher interest rates on offer. Measured by volume, the declines in the broad money supply have darn near all come from declines in M1 (again, the jump is redefinition). And of that, it’s almost entirely coming out of “other” liquid deposits, as illustrated above. That’s savings balances. It’s true that there is some other-other balances, but it’s mostly savings accounts.

Zooming in on just those “other” balances (below left), people still have higher balances than they did prior to the pandemic. But by now, they’re below the pre-pandemic trend. Savings accounts are depleted. However, since many people don’t use savings account anymore due to the decade plus of low interest rates, it’s appropriate to consider both “other” accounts and demand deposits (below right). By that measure, we still have plenty of post-Covid liquidity at our disposal.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1aFLo

*Other liquid deposits consist of negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) and automatic transfer service (ATS) balances at depository institutions, share draft accounts at credit unions, demand deposits at thrift institutions, and savings deposits, including money market deposit accounts.

PS. So where is all this above-trend NGDP coming from, if not the money supply? Hmmmm.