Here is a three-year chart of stock prices for Nvidia (NVDA), Alphabet/Google (GOOG), and the generic QQQ tech stock composite:

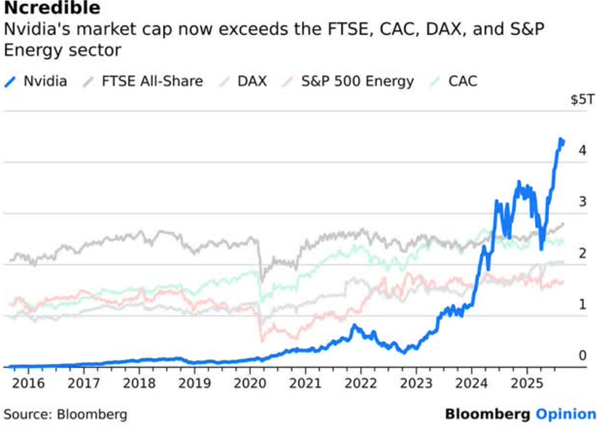

NVDA has been spectacular. If you had $20k in NVDA three years ago, it would have turned into nearly $200k. Sweet. Meanwhile, GOOG poked along at the general pace of QQQ. Until…around Sept 1 (yellow line), GOOG started to pull away from QQQ, and has not looked back.

And in the past two months, GOOG stock has stomped all over NVDA, as shown in the six-month chart below. The two stocks were neck and neck in early October, then GOOG has surged way ahead. In the past month, GOOG is up sharply (red arrow), while NVDA is down significantly:

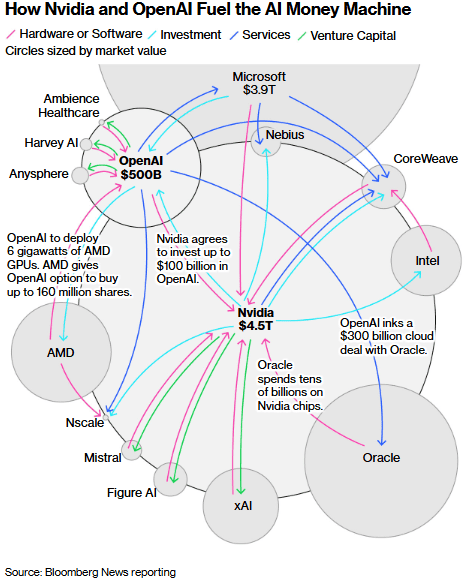

What is going on? It seems that the market is buying the narrative that Google’s Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) chips are a competitive threat to Nvidia’s GPUs. Last week, we published a tutorial on the technical details here. Briefly, Google’s TPUs are hardwired to perform key AI calculations, whereas Nvidia’s GPUs are more general-purpose. For a range of AI processing, the TPUs are faster and much more energy-efficient than the GPUs.

The greater flexibility of the Nvidia GPUs, and the programming community’s familiarity with Nvidia’s CUDA programming language, still gives Nvidia a bit of an edge in the AI training phase. But much of that edge fades for the inference (application) usages for AI. For the past few years, the big AI wannabes have focused madly on model training. But there must be a shift to inference (practical implementation) soon, for AI models to actually make money.

All this is a big potential headache for Nvidia. Because of their quasi-monopoly on AI compute, they have been able to charge a huge 75% gross profit margin on their chips. Their customers are naturally not thrilled with this, and have been making some efforts to devise alternatives. But it seems like Google, thanks to a big head start in this area, and very deep pockets, has actually equaled or even beaten Nvidia at its own game.

This explains much of the recent disparity in stock movements. It should be noted, however, that for a quirky business reason, Google is unlikely in the near term to displace Nvidia as the main go-to for AI compute power. The reason is this: most AI compute power is implemented in huge data/cloud centers. And Google is one of the three main cloud vendors, along with Microsoft and Amazon, with IBM and Oracle trailing behind. So, for Google to supply Microsoft and Amazon with its chips and accompanying know-how would be to enable its competitors to compete more strongly.

Also, AI users like say OpenAI would be reluctant to commit to usage in a Google-owned facility using Google chips, since then the user would be somewhat locked in and held hostage, since it would be expensive to switch to a different data center if Google tried to raise prices. On contrast, a user can readily move to a different data center for a better deal, if all the centers are using Nvidia chips.

For the present, then, Google is using its TPU technology primarily in-house. The company has a huge suite of AI-adjacent business lines, so its TPU capability does give it genuine advantages there. Reportedly, soul-searching continues in the Google C-suite about how to more broadly monetize its TPUs. It seems likely that they will find a way.

As usual, nothing here constitutes advice to buy or sell any security.