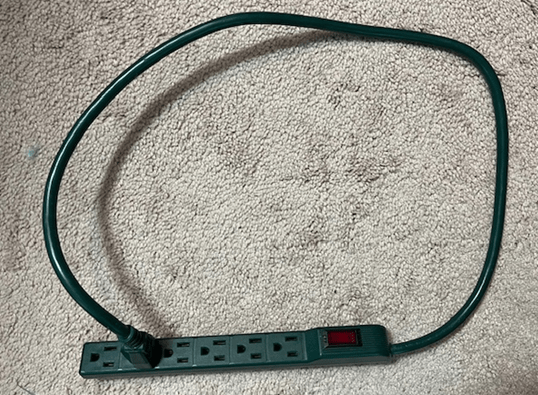

Hey look, I just found a way to get infinite free electric power:

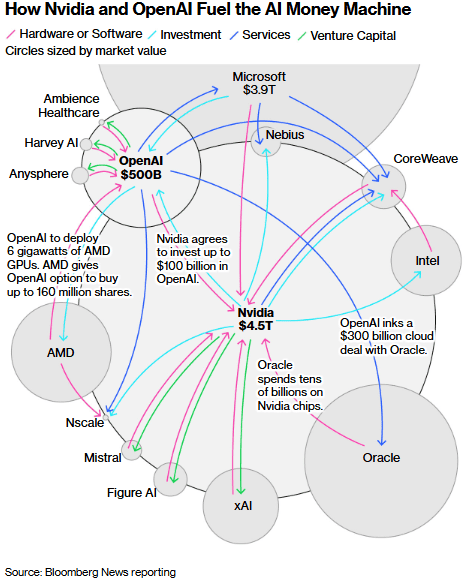

This sort of extension-cord-plugged-into-itself meme has shown up recently on the web to characterize a spate of circular financing deals in the AI space, largely involving OpenAI (parent of ChatGPT). Here is a graphic from Bloomberg which summarizes some of these activities:

Nvidia, which makes LOTS of money selling near-monopoly, in-demand GPU chips, has made investing commitments in customers or customers of their customers. Notably, Nvidia will invest up to $100 billion in Open AI, in order to help OpenAI increase their compute power. OpenAI in turn inked a $300 billion deal with Oracle, for building more data centers filled with Nvidia chips. Such deals will certainly boost the sales of their chips (and make Nvidia even more money), but they also raise a number of concerns.

First, they make it seem like there is more demand for AI than there actually is. Short seller Jim Chanos recently asked, “[Don’t] you think it’s a bit odd that when the narrative is ‘demand for compute is infinite’, the sellers keep subsidizing the buyers?” To some extent, all this churn is just Nvidia recycling its own money, as opposed to new value being created.

Second, analysts point to the destabilizing effect of these sorts of “vendor financing” arrangements. Towards the end of the great dot.com boom in the late 1990’s, hardware vendors like Cisco were making gobs of money selling server capacity to internet service providers (ISPs). In order to help the ISPs build out even faster (and purchase even more Cisco hardware), Cisco loaned money to the ISPs. But when that boom busted, and the huge overbuild in internet capacity became (to everyone’s horror) apparent, the ISPs could not pay back those loans. QQQ lost 70% of its value. Twenty-five years later, Cisco stock price has never recovered its 2000 high.

Beside taking in cash investments, OpenAI is borrowing heavily to buy its compute capacity. Since OpenAI makes no money now (and in fact loses billions a year), and (like other AI ventures) will likely not make any money for several more years, and it is locked in competition with other deep-pocketed AI ventures, there is the possibility that it could pull down the whole house of cards, as happened in 2000. Bernstein analyst Stacy Rasgon recently wrote, “[OpenAI CEO Sam Altman] has the power to crash the global economy for a decade or take us all to the promised land, and right now we don’t know which is in the cards.”

For the moment, nothing seems set to stop the tidal wave of spending on AI capabilities. Big tech is flush with cash, and is plowing it into data centers and program development. Everyone is starry-eyed with the enormous potential of AI to change, well, EVERYTHING (shades of 1999).

The financial incentives are gigantic. Big tech got big by establishing quasi-monopolies on services that consumers and businesses consider must-haves. (It is the quasi-monopoly aspect that enables the high profit margins). And it is essential to establish dominance early on. Anyone can develop a word processor or spreadsheet that does what Word or Excel do, or a search engine that does what Google does, but Microsoft and Google got there first, and preferences are sticky. So, the big guys are spending wildly, as they salivate at the prospect of having the One AI to Rule Them All.

Even apart from achieving some new monopoly, the trillions of dollars spent on data center buildout are hoped to pay out one way or the other: “The data-center boom would become the foundation of the next tech cycle, letting Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and others rent out intelligence the way they rent cloud storage now. AI agents and custom models could form the basis of steady, high-margin subscription products.”

However, if in 2-3 years it turns out that actual monetization of AI continues to be elusive, as seems quite possible, there could be a Wile E. Coyote moment in the markets: