This continues our occasional series on stock options for amateurs.

I find options to be a nice tool in my investing arsenal. The previous post in this series was Stock Options Tutorial 1. Options Fundamentals. That post dealt with buying options, to provide simple examples. For reasons to explained in a future post, I usually prefer to sell options. Anyway, here we will look briefly at how options are priced. It is important to get an intuitive understanding of this, in order to be comfortable actually using options in your account.

The current price of an option, if you wanted to buy or sell it, is called the premium. There are two components that go into the premium, the intrinsic value and the extrinsic (or “time”) value:

Source: OptionAlpha

Intrinsic Value of Options

The intrinsic value is easy to figure out, once you understand it. It is simply how much you would profit if you owned the option, and decided to exercise it right now. For instance, if you owned a call with a strike price of $50, but the stock price is $55, you could exercise the call and force whoever sold you the call to sell you the stock at a price of $50/share; you could turn around and immediately sell that share for $55, pocketing $5/share. We say that the option in this case is $5 in the money, and the intrinsic value is $5.

If the stock price were $60, it would be $10 in the money; you could pocket $10/share for exercising it. If the stock price were say $90, the option would be $40 in the money, and so on.

However, if the stock price were $50 (the $50 option is “at the money”) or lower (option is “out of the money”), you would get no benefit from being able to purchase this stock for $50, and so the intrinsic value of the option would be zero.

With a put (which is an option to sell a stock at a particular price), this is all reversed. If the stock is $5 lower than the option strike price, the option is $5 in the money and has a $5 intrinsic value, since if you own it, you could say buy the stock at $45, and force the put option seller to buy it from you at $50/share:

Source: OptionAlpha

Extrinsic (Time) Value of Options

Suppose the current price of a stock is $50. And suppose you suspect its price may be above $50, say $60 sometime in the next month, so you would like to have the option of buying it at $50 sometime in the future, and then selling it into the market at (say) $60, for a quick, guaranteed profit of $10. Sounds great, yes?

Since a $50 call is right at the money (since the stock price is also $50), the intrinsic value of a $50 call is zero. Does this mean you could go out and buy a $50 call option for nothing? No, because the seller of the option is taking a risk by providing you that option. If the stock really does go to $60, he could be out the $10. Therefore, he will demand a higher price than the intrinsic price, to make it worth his while. This extra premium over the intrinsic premium is the extrinsic premium, which varies greatly with the time till expiration of the option.

If you wanted the option of buying the stock at $50 sometime in the next week, the option seller would charge only a small amount; after all, what are the odds that the stock will rise a lot in one week? However, if you wanted to extend that option period out to one year, he will charge you a high extrinsic premium, since there is a bigger chance that the stock could soar will over $50 sometime in that long timeframe.

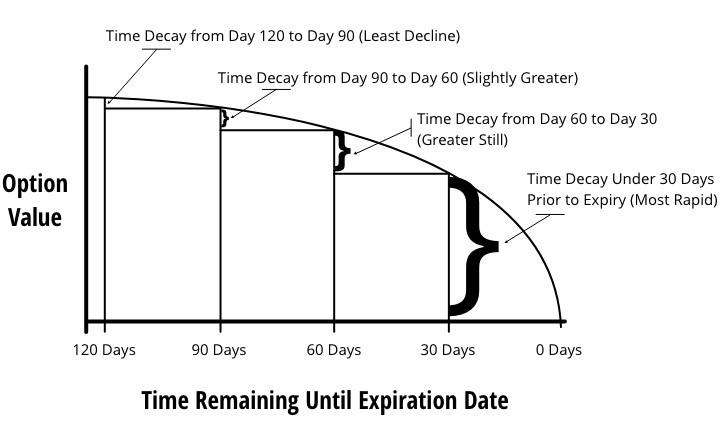

Another way of framing this is, if you buy a $50 call option today with an expiration date a year from now, you will pay a high extrinsic value. But as the months roll by, and it gets closer to the expiration date, this extrinsic value or time premium will shrink down ever more quickly towards zero:

Source: QuantStackExchange, on Seeking Alpha

Now, computing the actual amount of the extrinsic value is really gnarly. The Black-Scholes model provides a theoretical value under idealized conditions, but for us amateurs, we pretty much have to just take what the market gives us. In deciding whether to buy or sell an option, I look at what the current market pricing is for it.

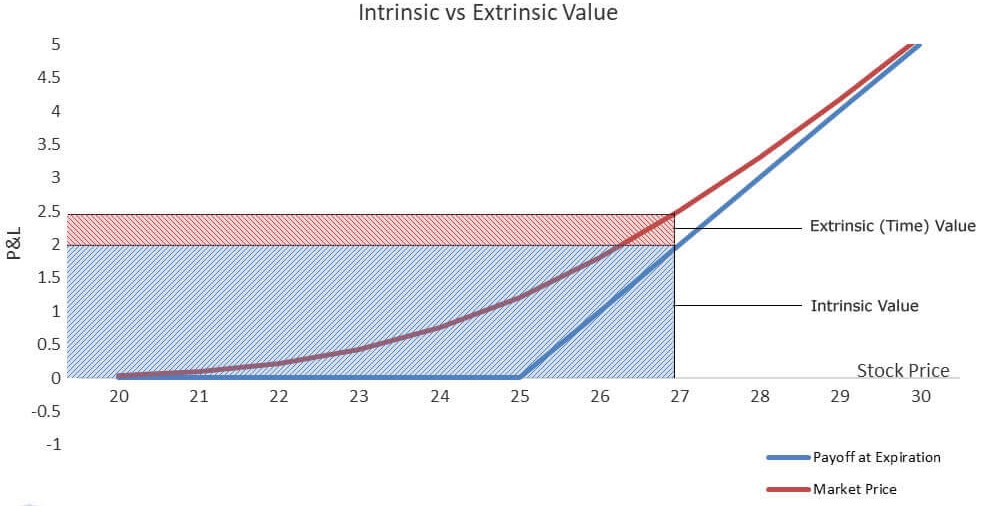

It turns out that an option which is priced at the money has the highest extrinsic value. As you get further into or out of the money, the extrinsic component of the total premium for the option diminishes. Below is one final graphic which pulls all this together:

Source: OptionTradingTips

The call option strike price is $25. The blue line shows the intrinsic value (labeled as “payoff at expiration”) at each stock price – this is zero at or below $25, and increases 1:1 as the stock price climbs above $25. The red curve shows the full market price of the option, including the extrinsic (time) premium. The spacing between the red and the blue lines shows the amount of the extrinsic premium. That spacing is greatest when the stock price is equal to the $25 strike price. The shaded areas specify the intrinsic and extrinsic values at a stock price of $27.

And (not shown here) as time passed and the option got closer to expiry, the extrinsic value would shrink (decay), and the red curve would creep closer and closer to the blue curve.