I invested in my first private company in 2022; my first opportunity to cash out of a private investment came this year when Our Bond did an IPO, now trading on Nasdaq as OBAI.

I’m happy to get a profitable exit less than 4 years after my first investment, given that I’m investing in early-stage companies. Venture funds tend to run for 10 years to give their companies time to IPO or get acquired, and WeFunder (the private investment platform I used) says that “On average, companies on Wefunder that earn a return take around 7 years to do so.” The speed here is especially striking given that I didn’t invest in Our Bond itself until April 2025.

Most private companies that raise money from individual investors are very early stage, what venture capitalists would call “pre-seed” or “seed-stage” companies looking for angel investors. Later-stage companies often find it simpler to raise their later stages (Series B, et c) from a few large institutional investors. But a few choose to do “community rounds” and allow individuals to invest later. This is what Our Bond did right before their IPO, allowing me to exit in less than a year.

This helps calm my biggest concern with equity crowdfunding- adverse selection:

The companies themselves have a better idea of how well they are doing, and the best ones might not bother with equity crowdfunding; they could probably raise more money with less hassle by going to venture funds or accredited angel investors.

My guess is that the reason some good companies bother with this is marketing. Why did Substack bother raising $7.8 million from 6000 small investors on WeFunder in 2023, when they probably could have got that much from a single VC firm like A16Z? They got the chance to explain how great their company and product is to an interested audience, and to give thousands of investors an incentive to promote the company. Getting one big check from VCs is simpler, but it doesn’t directly promote your product in the same way.

All this is enough to convince me that the equity crowdfunding model enabled by the 2012 JOBS Act will continue to grow.

Still, things could have easily gone better for me, as these markets are clearly inefficient and have complexities I’m still learning to navigate. Profitability is not just about choosing the right companies to invest in, but about managing exits. I expected the typical IPO roadshow would give me months of heads-up, but Our Bond surprised its investors with a direct listing. The first thing I heard about the IPO was a February 4th email from “VStockTransfer” that I thought was a scam at first, since it was a 3rd-party company I’d never heard of asking me to pay them money to access my shares. But Our Bond confirmed it was real- VStockTransfer was the custodian for the private shares, and charges $120 to “DRS transfer” them to a brokerage of your choice where they can be sold.

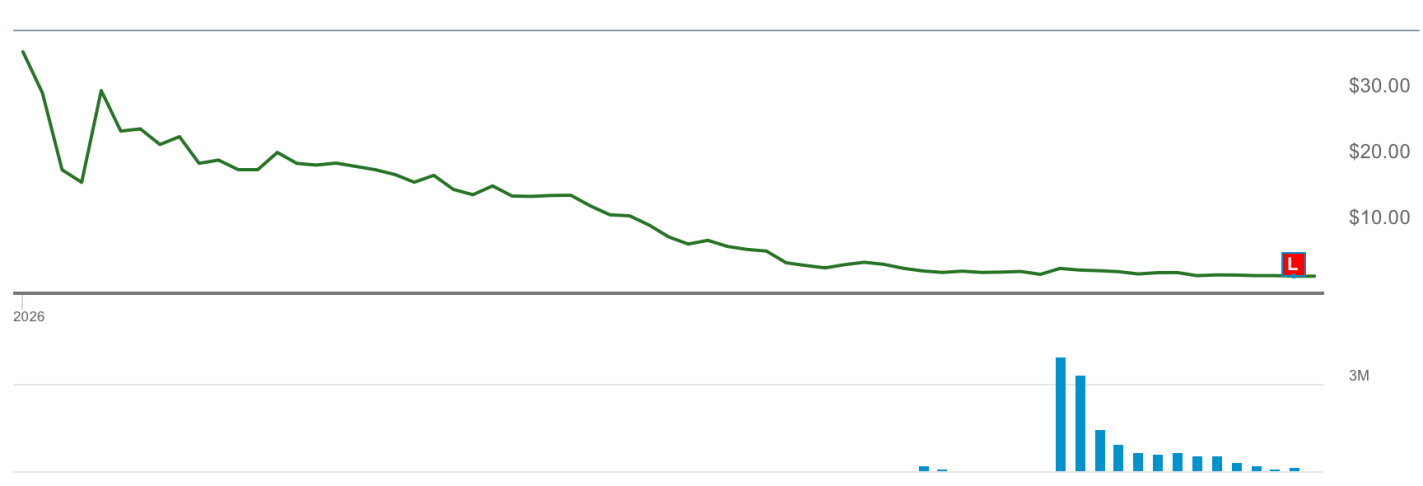

I submitted the request to move the shares to Schwab the same day, but Schwab estimated it would take a week to move them. Neither Schwab nor VStockTransfer ever sent me a notification that the shares had been transferred, and by the time I noticed they had moved a week later, the stock price had fallen dramatically:

As I write this on February 18th, the OBAI price represents a 1.3x return on the price I invested in the private company at last April. When I was first able to sell some stock on February 11th, the price represented a 3x return; if I’d been able to sell right away on the 4th without waiting for the brokerage transfer process, it would have been a 10x return.

By the Efficient Market Hypothesis this timing shouldn’t be so critical, but I knew there would be a rush for the exits as lots of private investors would want to unload their shares at the first opportunity, an opportunity some would have waited years for. Sometimes old-fashioned supply and demand analysis is a better guide to markets than the EMH: demand for OBAI stock had no big reason to change in February, but freely floating supply saw a big increase as private shares got unlocked and moved to brokerages.

Getting a 10x return vs a 1.3x return on one of your winners is the difference between a great early investor and a bad one. I always thought such differences would be driven by who picks the best companies to invest in, but at least in this case it could be driven by who is fastest on the draw with brokerage transfers.

If I ever find myself holding shares in another company that does a direct listing, I’ll be doing whatever I can to make sure the transfer goes as fast as possible (pick the fastest brokerage, check on the transfer status every day, et c). This process also seems like one reason to do fewer, larger private investments- a fixed $120 transfer fee is a big deal if the initial investment was in the low hundreds but wouldn’t matter much for a larger one.

Being accredited would help there, allowing access to additional later-stage, less-risky companies. But I’ll call OBAI a win for equity crowdfunding, and a big win for asset pricing theories based on liquidity and flows over efficient estimation of the present discounted value of future cashflows.

Disclaimer: I still hold some OBAI