Last Tuesday I posted on the topic, “Tech Stocks Sag as Analysists Question How Much Money Firms Will Actually Make from AI”. Here I try to dig a little deeper into the question of whether there will be a reasonable return on the billions of dollars that tech firms are investing into this area.

Cloud providers like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google are building buying expensive GPU chips (mainly from Nvidia) and installing them in power-hungry data centers. This hardware is being cranked to train large language models on a world’s-worth of existing information. Will it pay off?

Obviously, we can dream up all sorts of applications for these large language models (LLMs), but the question is much potential downstream customers are willing to pay for these capabilities. I don’t have the capability for an expert appraisal, so I will just post some excerpts here.

Up until two months ago, it seemed there was little concern about the returns on this investment. The only worry seemed to be not investing enough. This attitude was exemplified by Sundar Pichai of Alphabet (Google). During the Q2 earnings call, he was asked what the return on Gen AI investment capex would be. Instead of answering the question directly, he said:

I think the one way I think about it is when we go through a curve like this, the risk of under-investing is dramatically greater than the risk of over-investing for us here, even in scenarios where if it turns out that we are over investing. [my emphasis]

Part of the dynamic here is FOMO among the tech titans, as they compete for the internet search business:

The entire Gen AI capex boom started when Microsoft invested in OpenAI in late 2022 to directly challenge Google Search.

Naturally, Alphabet was forced to develop its own Gen AI LLM product to defend its core business – Search. Meta joined in the Gen AI capex race, together with Amazon, in fear of not being left out – which led to a massive Gen AI capex boom.

Nvidia has reportedly estimated that for every dollar spent on their GPU chips, “the big cloud service providers could generate $5 in GPU instant hosting over a span of four years. And API providers could generate seven bucks over that same timeframe.” Sounds like a great cornucopia for the big tech companies who are pouring tens of billions of dollars into this. What could possibly go wrong?

In late June, Goldman Sachs published a report titled, GEN AI: TOO MUCH SPEND,TOO LITTLE BENEFIT?. This report included contributions from bulls and from bears. The leading Goldman skeptic is Jim Covello. He argues,

To earn an adequate return on the ~$1tn estimated cost of developing and running AI technology, it must be able to solve complex problems, which, he says, it isn’t built to do. He points out that truly life-changing inventions like the internet enabled low-cost solutions to disrupt high-cost solutions even in its infancy, unlike costly AI tech today. And he’s skeptical that AI’s costs will ever decline enough to make automating a large share of tasks affordable given the high starting point as well as the complexity of building critical inputs—like GPU chips—which may prevent competition. He’s also doubtful that AI will boost the valuation of companies that use the tech, as any efficiency gains would likely be competed away, and the path to actually boosting revenues is unclear.

MIT’s Daron Acemoglu is likewise skeptical: He estimates that only a quarter of AI-exposed tasks will be cost-effective to automate within the next 10 years, implying that AI will impact less than 5% of all tasks. And he doesn’t take much comfort from history that shows technologies improving and becoming less costly over time, arguing that AI model advances likely won’t occur nearly as quickly—or be nearly as impressive—as many believe. He also questions whether AI adoption will create new tasks and products, saying these impacts are “not a law of nature.” So, he forecasts AI will increase US productivity by only 0.5% and GDP growth by only 0.9% cumulatively over the next decade.

Goldman economist Joseph Briggs is more optimistic: He estimates that gen AI will ultimately automate 25% of all work tasks and raise US productivity by 9% and GDP growth by 6.1% cumulatively over the next decade. While Briggs acknowledges that automating many AI-exposed tasks isn’t cost-effective today, he argues that the large potential for cost savings and likelihood that costs will decline over the long run—as is often, if not always, the case with new technologies—should eventually lead to more AI automation. And, unlike Acemoglu, Briggs incorporates both the potential for labor reallocation and new task creation into his productivity estimates, consistent with the strong and long historical record of technological innovation driving new opportunities.

The Goldman report also cautioned that the U.S. and European power grids may not be prepared for the major extra power needed to run the new data centers.

Perhaps the earliest major cautionary voice was that of Sequoia’s David Cahn. Sequoia is a major venture capital firm. In September, 2023 Cahn offered a simple calculation estimating that for each dollar spent on (Nvidia) GPUs, and another dollar (mainly electricity) would need be spent by the cloud vendor in running the data center. To make this economical, the cloud vendor would need to pull in a total of about $4.00 in revenue. If vendors are installing roughly $50 billion in GPUs this year, then they need to pull in some $200 billion in revenues. But the projected AI revenues from Microsoft, Amazon, Google, etc., etc. were less than half that amount, leaving (as of Sept 2023) a $125 billion dollar shortfall.

As he put it, “During historical technology cycles, overbuilding of infrastructure has often incinerated capital, while at the same time unleashing future innovation by bringing down the marginal cost of new product development. We expect this pattern will repeat itself in AI.” This can be good for some of the end users, but not so good for the big tech firms rushing to spend here.

In his June, 2024 update, Cahn notes that now Nvidia yearly sales look to be more like $150 billion, which in turn requires the cloud vendors to pull in some $600 billion in added revenues to make this spending worthwhile. Thus, the $125 billion shortfall is now more like a $500 billion (half a trillion!) shortfall. He notes further that the rapid improvement in chip power means that the value of those expensive chips being installed in 2024 will be a lot lower in 2025.

And here is a random cynical comment on a Seeking Alpha article: It was the perfect combination of years of Hollywood science fiction setting the table with regard to artificial intelligence and investors looking for something to replace the bitcoin and metaverse hype. So when ChatGPT put out answers that sounded human, people let their imaginations run wild. The fact that it consumes an incredible amount of processing power, that there is no actual artificial intelligence there, it cannot distinguish between truth and misinformation, and also no ROI other than the initial insane burst of chip sales – well, here we are and R2-D2 and C3PO are not reporting to work as promised.

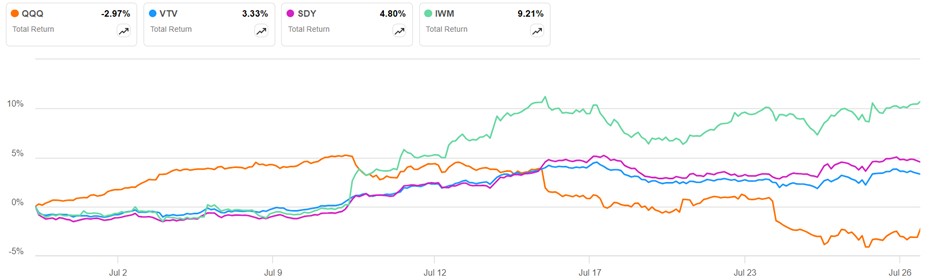

All this makes a case that the huge spends by Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and the like may not pay off as hoped. Their share prices have steadily levitated since January 2023 due to the AI hype, and indeed have been almost entirely responsible for the rise in the overall S&P 500 index, but their prices have all cratered in the past month. Whether or not these tech titans make money here, it seems likely that Nvidia (selling picks and shovels to the gold miners) will continue to mint money. Also, some of the final end users of Gen AI will surely find lucrative applications. I wish I knew how to pick the winners from the losers here.

For instance, the software service company ServiceNow is finding value in Gen AI. According to Morgan Stanley analyst Keith Weiss, “Gen AI momentum is real and continues to build. Management noted that net-new ACV for the Pro Plus edition (the SKU that incorporates ServiceNow’s Gen AI capabilities) doubled [quarter-over-quarter] with Pro Plus delivering 11 deals over $1M including two deals over $5M. Furthermore, Pro Plus realized a 30% price uplift and average deal sizes are up over 3x versus comparable deals during the Pro adoption cycle.”