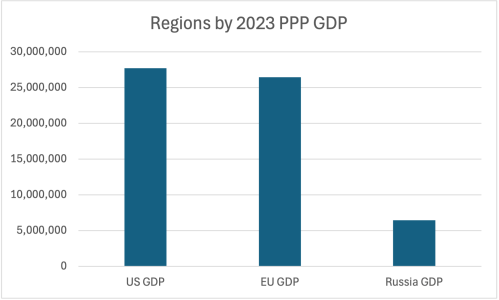

The Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee is proposing to cut off student loans for programs whose graduates earn less than the median high school graduate. The House proposed a risk-sharing model where colleges would partly pay back the federal government when their students fail to pay back loans themselves. Both the House and Senate propose to cap how much students can borrow for graduate loans. Both would reduce federal spending on higher ed by about $30-$35 billion per year, cutting the size of the $700 billion higher ed sector by 4-5%. I expected that something like this would happen eventually, especially after the student loan forgiveness proposals of 2022:

While we aren’t getting real reform now, I do think forgiveness makes it more likely that we’ll see reform in the next few years. What could that look like?

The Department of Education should raise its standards and stop offering loans to programs with high default rates or bad student outcomes. This should include not just fly-by-night colleges, but sketchy masters degree programs at prestigious schools.

Colleges should also share responsibility when they consistently saddle students with debt but don’t actually improve students’ prospects enough to be able to pay it back. Economists have put a lot of thought into how to do this in a manner that doesn’t penalize colleges simply for trying to teach less-prepared students.

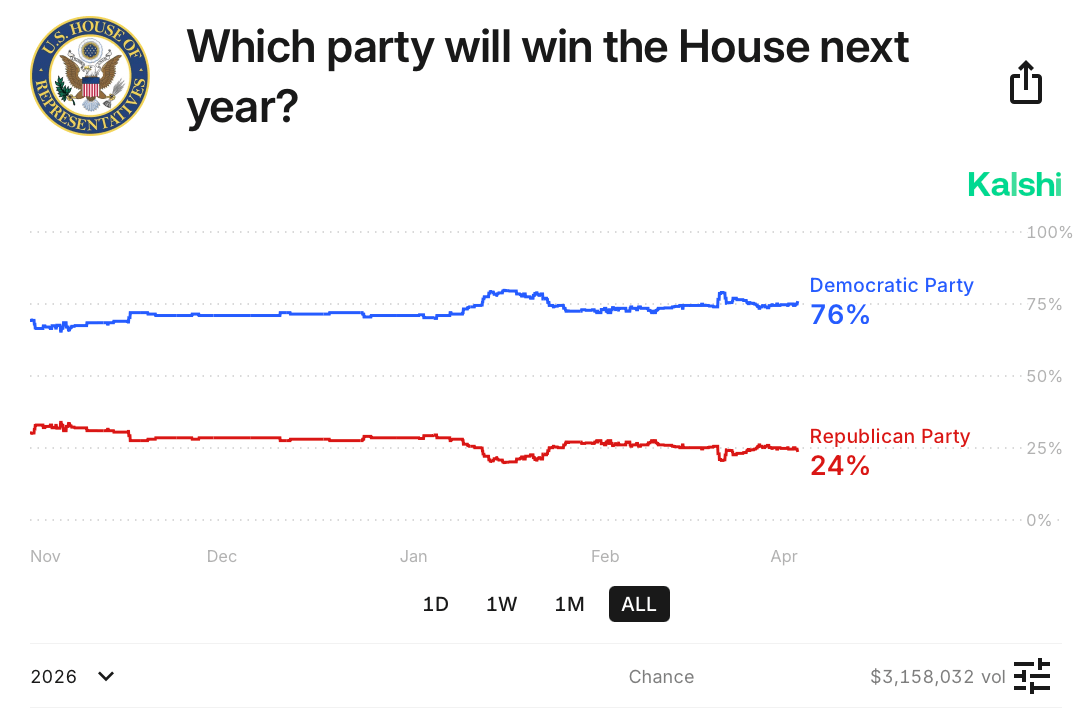

I’d bet that some reform along these lines happens in the 2020’s, just like the bank bailouts of 2008 led to the Dodd-Frank reform of 2010 to try to prevent future bailouts. The big question is, will this be a pragmatic bipartisan reform to curb the worst offenders, or a Republican effort to substantially reduce the amount of money flowing to a higher ed sector they increasingly dislike?

Of course, there is a lot riding on the details. How exactly do you calculate the income of graduates of a program compared to high school grads? The Senate proposal explains their approach starting on page 58. They want to compare the median income of working students 4 years after leaving their program (whether they graduated or dropped out, but exempting those in grad school) to the median income of those with only a high school diploma who are age 25-34, working, and not in school.

Nationally I calculate that this would make for a floor of $31,000. That is, the median student who is 4 years out from your program and is working should be earning at least $31k. In practice the bill would implement a different number for each state. This seems like a low bar in general, though you could certainly quibble with it. For instance, those 4 years out from a program may be closer to age 25 than age 34, but income typically rises with age during those years. If you compare them to 26 year old high school grads, the national bar would be just $28k.

What sorts of programs have graduates making less than $31k per year?

Continue reading