Two weeks in and it’s safe to say the United States federal government has been shocked out of it’s previous equilibrium (whether that shock is “exogenous” is honestly besides the point). Some thoughts, in no particular order

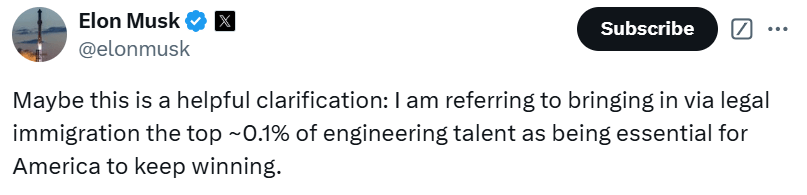

The federal talent drain is going to get even worse

At some point in the last 100 years the equilibrium strategy for the government has been to pay employees in the non-pecuniary benefits of a) job security, b) status, c) retirement d) pro-social civic pride, and e) still more job security. Almost none of that remains wholly intact. The previous bundle of non-pecuniaries resulted in a federal labor force where, glibly estimated, 20% of the employees did 80% of the work. The federal government functioned off the talent and committment of employees whose non-pecuniary preferences led them to forego considerable amounts of income in the private sector. Not sure who’s going to stick around or start a career in the federal government at this point, but I expect the selection effects to be sometimes darkly tragicomic, but mostly just tragic. People have already been hurt. More people will continue to be hurt.

The shrill cranks were right

It’s time for a lot of people to start publicly accepting the fact that the new administration is actually running an authoritarian playbook. Words like “fascism” are neither shrill nor overwrought. Is it unfortunate that people have being making accusations of fascist intent everyday for the last 30 years? Yes, but just because they were wrong then doesn’t mean it’s inappropriate now. The stopped clock is in fact right twice a day. Guess what time it is?

On raptors and resistance

If you’re looking for metaphor instead of adjectives, the new administration are raptors testing their cages for weakpoints, seeing what they can get away with. The bad news is that they are finding no shortage of potential weaknesses to advance their agenda. The good news is that finding and exploiting weaknesses takes time. If we are willing to accept that tariffs are going to impose a lot of price-related pain on consumers and, as the previous round of elections around the world has evidenced, voters do in fact punish incumbents for consumer pain, then the optimal strategy is to merely survive the next 206 weeks with as little damage as possible. So how do we do that?

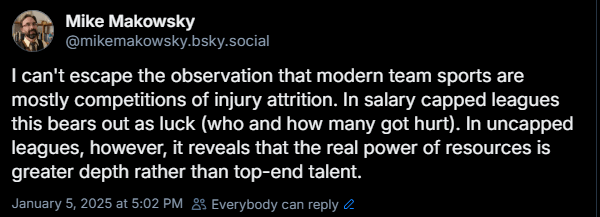

Put simply, waste time. The entire opposition strategy should be to force the administration to use as much time as possible at every step. Procedural, judicial, and legislative moves are all available. Aspiring fascists they may be, but they are not particularly competent fascists. These people are not grinding out 16 hour work days to write air tight executive orders. They are not career bureacrats who know exactly what buttons to push. They are carnival barkers, reality tv producers, third-rate social media influencers, and niche celebrities. Every time they make a misstep, design something poorly, and have to rescind it 44 hours later? That’s a win. It’s wasted time on a ticking clock that they will never get back. It doesn’t feel like a win because it imposed a lot of pain on a lot of people, but that pain fell well short of the administration’s ambitions.

This works for the tariffs as well. This is not the 18th century where you would simply put someone with a coin purse on the docks to inspect and collect tariffs from every ship that came to port. Modern supply chains are outrageously complex. Collecting tariffs effectively requires institutional infrastructure closer to a VAT tax. Do you really they think these people are going to design it in a manner impervious to bureaucratic and market resistance on the first or second try? Resistance means tying things up in courts on one side while publicly broadcasting the loopholes for the marketplace on the other. Resistance means not just smiling when Canada designs retaliatory tariffs that target “red state” produced goods, but actively broadcasting and supporting that targeting (he wrote while living in a red state and knows he should probably stock up on maple syrup).

Complaining in Stereo

Incumbents lost around the world because nothing pierces rational voter ignorance quite like inflation. Unemployment is salient, but until you hit ~8% or more it might not be sufficiently pervasive to move enough votes. The converse is even more true – it’s almost impossible to get credit for high employment because all you really know is that you have a job which you would have had anyway because you are good and smart and deserve to have a job. Higher prices though, those are always someone else’s fault. The current adminstration blamed Democrats and foreigners. Now it’s the new opposition’s turn to blame Republicans and incompetent public figures in the bureacracy. When consumers take it on the chin, the opposition needs to amplify, amplify, amplify. If there is one thing that seems to be universally true in the modern social media age, it’s that few things are as welcomed by the audience as anxiety and anger. People love to complain. I see no reason not to feed that complaining.