I’m in the process of writing a review of Jon Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation. I wrote some preliminary thoughts a few weeks ago, but I’m diving a lot deeper now, so watch for that review soon. But one of the main startling pieces of data in the book is the dramatic rise in suicides among young girls. Haidt isn’t the first to point this out, but in large part his book is an attempt to explain this rise (as well as the rise among boys and slightly older girls).

This got me thinking a bit more broadly about not just suicides, but all causes of mortality among young Americans. So in the style of my 2022 post about the leading causes of death among men ages 18-39, let’s look at the historical trends for deaths among girls 10-14 in the US.

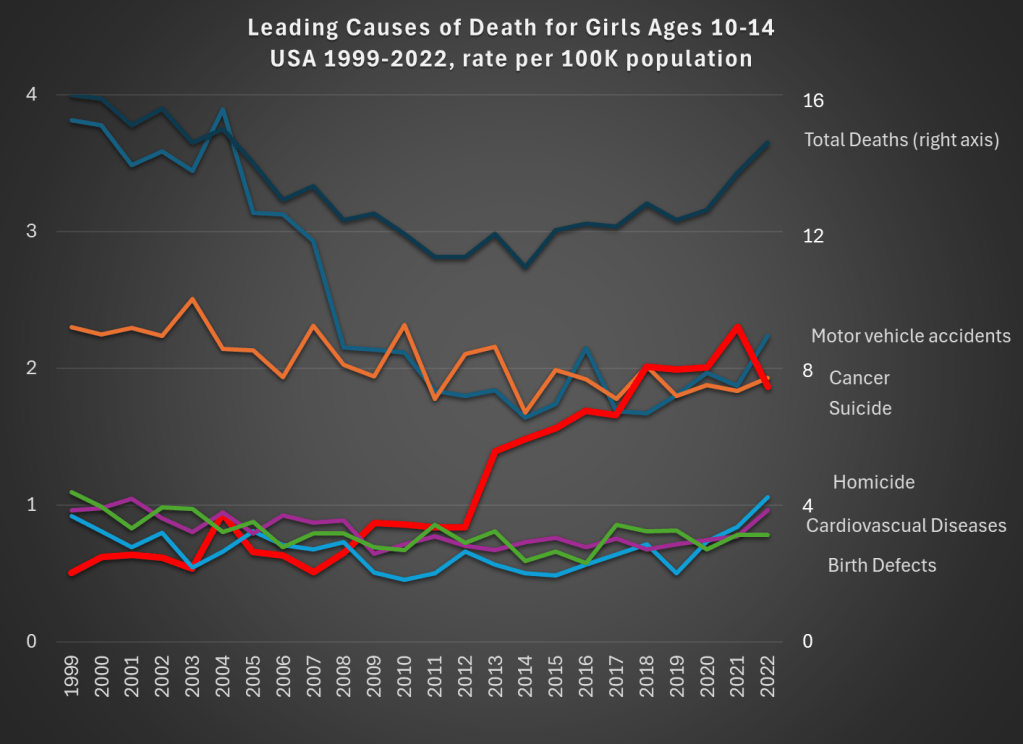

Data comes from CDC WONDER. The top dark line shows total deaths, and the scale for total deaths is the right-axis. Notice that for total deaths, there is a U-shaped pattern. From 1999 to about 2012, deaths for girls aged 10-14 are falling. Then, the bottom out and start to rise again. While the end point in 2022 is lower than 1999 (by about 9 percent), there is a 22 percent increase from 2010 to 2022.

What’s driving those trends? A fall in motor vehicle accidents (blue line, the leading cause of death in both 1999 and 2022) is driving the decline. This category fell 41 percent over the entire time period: a big drop for the leading cause of death!

But the rise in suicides (thick red line) starting in 2013 is the clear driver of the reversal of the overall trend. Suicides for this demographic in 2022 were 268 percent higher than 1999, and 116 percent higher than 2010. Haidt and others are right to investigate the causes of this trend (I’m not convinced they have the complete answer, but more on that in my forthcoming book review).

There has been no clear trend in cancer deaths over this time period, and the combination of all the three of these trends means that roughly equal number of girls ages 10-14 die from car accidents, suicide, and cancer.

What can we learn from this data? First, we should acknowledge just how rare death is for girls ages 10-14. At 14.8 deaths per 100,000 population, it is the lowest 5-year age-gender cohort, other than the ages just below it (ages 5-9, for both boys and girls). But just because it is small doesn’t mean we should ignore it. The big increase, especially in suicides, in the past decade is worrying and could be indicative of broader worrying social trends (and suicides have risen for almost every age group too, see my linked post above).

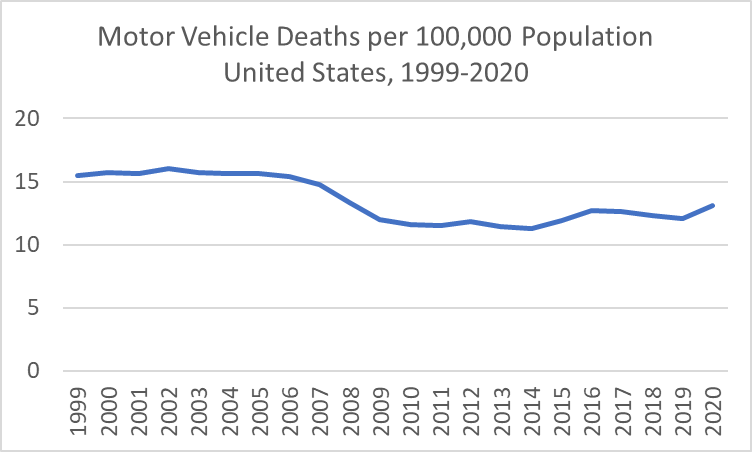

If a concern, though, is that we are over-protecting our kids and this is leading them to retreat into a world of social media, we might want to see if there are any benefits of this overprotection in addition to the costs. The decline in motor vehicle accidents is one candidate. Is this decline just a result of the overall increase in car safety? Or is there something specific going on that is leading to fewer deaths among young teens and pre-teens?

As we know from other data, a lot fewer young people are getting driver’s licenses these days, especially compared to 1999 (and engaging in fewer risky behaviors across the board). Of course, 10-14 year-olds themselves usually weren’t the ones getting licenses — they are too young in most states — but their 15 and 16 year-old siblings might be the ones driving them around. Is fewer teens driving around their pre-teen siblings a cause of the decline in motor vehicle deaths? We can’t tell from this data, but it is worth investigating further (note: best I can tell, only about 23 percent of the decline is from fewer pedestrian deaths, though in the long-run this is a bigger factor).

Social tradeoffs are hard. If there really is a tradeoff between fewer car accident deaths and more suicides, how should we think about that tradeoff? Or is the tradeoff illusory, and we could actually have fewer deaths of both kinds? I don’t think I know the answer, but I do think that many others are being way too confident that they have the answer based on what data we have so far.

One final note on suicides. For all suicides in the US, the most common method is suicide by firearm: about 55% of suicides in the US were committed with guns in 2022, with suffocations a distant second at about 25%. For girls ages 10-14, this is not the case, with suffocation being by far the leading method: 62% versus just 17% with firearms. I only mention this because some might think the increasing availability of firearms is the reason for the rise in suicides. It could be true overall, but it’s not the case for young girls.