Talk to some economists and they’ll tell you that exchange rates aren’t economically important. They say that exchange rates between countries are a reflection of supply and demand for one another’s stuff. So, at the macro, it’s a result and not a determinant of transnational economic activity.

For individual firms at the micro level, it’s the opposite. They don’t affect the exchange rate by their lonesome and are instead affected by it. If you have operations in a foreign country, then sudden changes to the exchange rate can cause your costs to be much higher or lower than you had anticipated. The same is true when you sell in a foreign country, but for revenues. This type of risk is called ‘exchange rate risk’ since it’s possible that none of the prices in either country changed and yet your investment returns change merely because of an appreciated currency.

Supply & Demand

Exchange rates are determined by supply and demand for currencies. Demand is driven by what people can do with a currency. If a country’s goods become more attractive, then demand for those goods rise and demand for the currency rises. After all, most retailers and wholesalers in the US require that you pay using US dollars. Importantly, it’s not just manufacturing goods that drive demand for currency. Demand for services, real estate, and financial assets can also affect the supply and demand for currency. In fact, many foreigners are specifically interested in stocks, bonds, US treasuries, and other investments. The more attractive all of those things are, the more demand there is for them.

Of course, the market for currency also includes suppliers. Who does that? Answer: Anyone who holds dollars and might buy something. Indeed, all buyers of goods or financial products are suppliers of their medium of exchange. In the US, we pay in dollars. Especially since 1972, suppliers have also included other central banks and governments. They treat the US currency as if it’s a reserve of value, such as gold, that can be depended upon if they need a valuable asset (hence the name, “Federal Reserve”). This is where the term ‘reserve currency’ comes from – not from the dollar-denominated prices of some internationally traded commodities. Though, that’s come to be an adopted meaning.

Another major supplier of currency is the US central bank. It has the advantage of being able to print US dollars. But it doesn’t have an exchange rate policy. So, it’s not targeting a particular price of the US dollar versus any other currency. The Fed does engage in some international reserve lending, but it’s not for the purpose of supplying currency to foreign exchange markets.

The US Exchange Rate in 2025

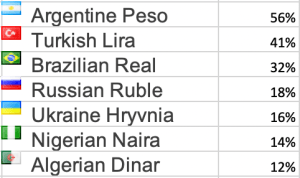

One of the reasons that the US has such popular financial assets is that we have highly developed financial markets and the rule of law. People trust that, regardless of the individual performance of an asset, the rules of the game are mostly known and evenly applied. For example, we have a process to follow when bond issuers default. So, our popularity is not merely because our assets have higher returns. Rather, US investment returns have dependably avoided political risk – relative to other countries anyway.

Continue reading