What I’m telling my Intro Macro students on the last day of class, since we weren’t able to get through every chapter in the textbook:

A few of you might end up working in economic policy, or in highly macro-sensitive businesses like finance. For you, I recommend taking followup classes like Intermediate Macroeconomics or Money and Banking so you can understand the details. For everyone else, here are the very basics:

- In the long run, economic growth is what matters most. The difference between 2% and 3% real GDP growth per capita sounds small in a given year, but over your lifetime it is the difference between your country becoming 5 times better off vs 10 times better off.

- How to increase long-run economic growth? This is complicated and mostly not driven by traditional macroeconomic policy, but rather by having good culture, institutions, microeconomic policy, and luck.

- In the shorter run, you want to avoid recessions and bursts of inflation.

- High inflation means too many dollars chasing too few goods. To fix it, the federal government and the central bank need to stop printing so much money (the details can get very complicated here, but if we’re talking moderately high inflation like 5% the solution is probably the central bank raising interest rates, and if we’re talking very high inflation like 50% the solution is probably a big cut to government spending).

- If there is a recession (which will look to you like a big sudden increase in layoffs and bankruptcies), the solution is probably to reverse everything in the previous point. The government should make money ‘easier’ via the central bank lowering interest rates while the federal government spends more and taxes less.

- If you don’t take more economics classes, you will likely hear about macro issues mainly through the news media and social media. You should be aware of their two main biases: negativity bias and political bias.

- Negativity Bias: If It Bleeds, It Leads on the news. Partly this is because bad news tends to happen suddenly while good news happens slowly, so it doesn’t seem like news; partly it just seems to be what people want from the news and from social media.

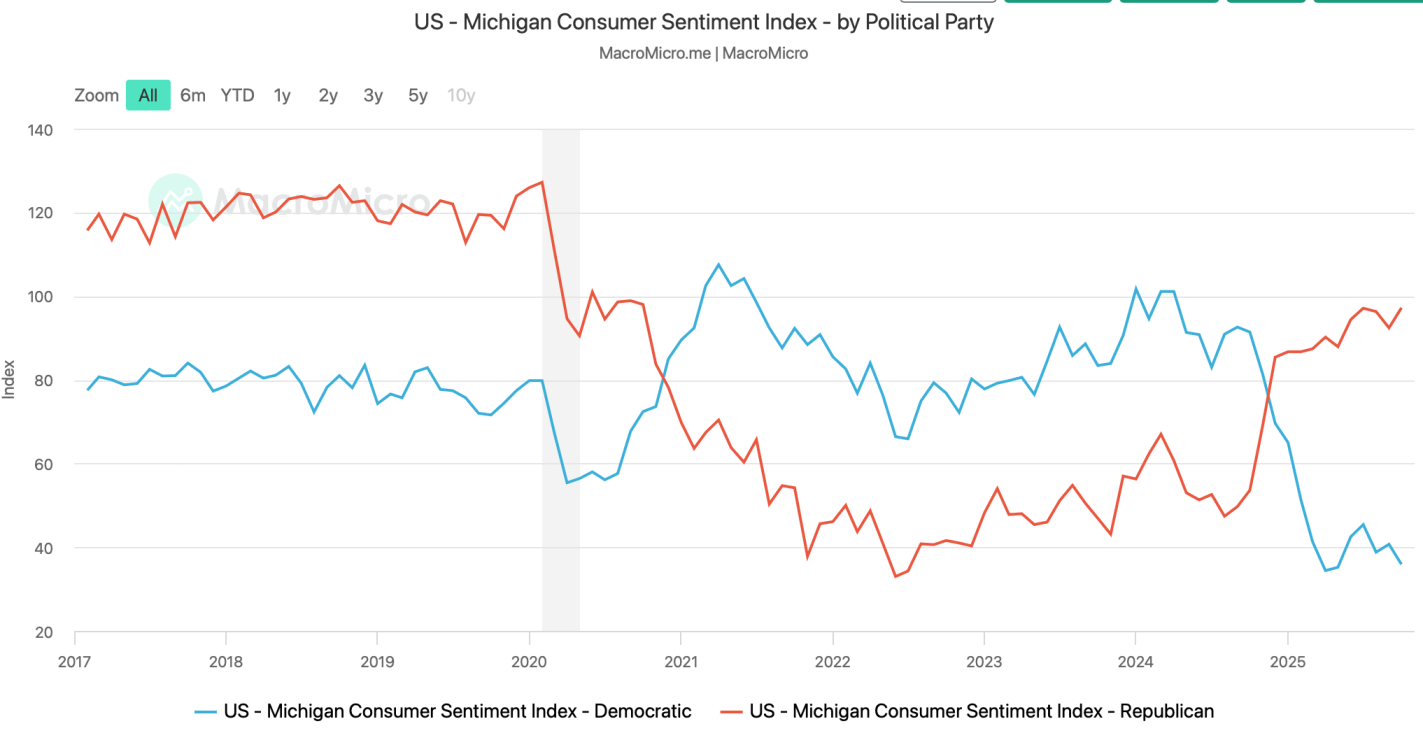

- Political Bias: People tend to seek out news and social media sources that match their current preferences. These sources can be misleading in consistent ways for ideological reasons, or in varying ways based on whether the political party they like is currently in power.

- There are different ways to measure each key macroeconomic variable. Think through them now and make a principled decision about which ones you think are the best measures, and track those. Otherwise, your media ecosystem will cherry-pick for you whichever measures currently make the economy look either the best or the worst, depending on what their biases or incentives dictate.

- There are good ways to keep learning about economics outside of formal courses and textbooks, I list a few here.