When reading an old novel or watching a period drama movie or TV show, it is almost inevitable that some historical currency amounts will be mentioned. This is especially true when the work is dealing with money and wealth, for example the series “The Gilded Age” is about rich people in late 19th century America. So money comes up a lot. I wrote a post a few weeks ago trying to contextualize a figure of $300,000 from 1883 for that show.

A new Netflix series “The House of Guinness” is another period piece that spends a lot of time focusing on rich people (the family that produces the famous beer), as well as their interactions with poorer folks. So of course, there are plenty of historical currency values mentioned, this time denominated in British pounds (the series is primarily set in Ireland, where the pound was in use). On this series, though, they have taken the interesting approach of giving the viewers some idea of what historical currency values are worth today, by overlaying text on the screen (the same way they translate the Gaelic language into English).

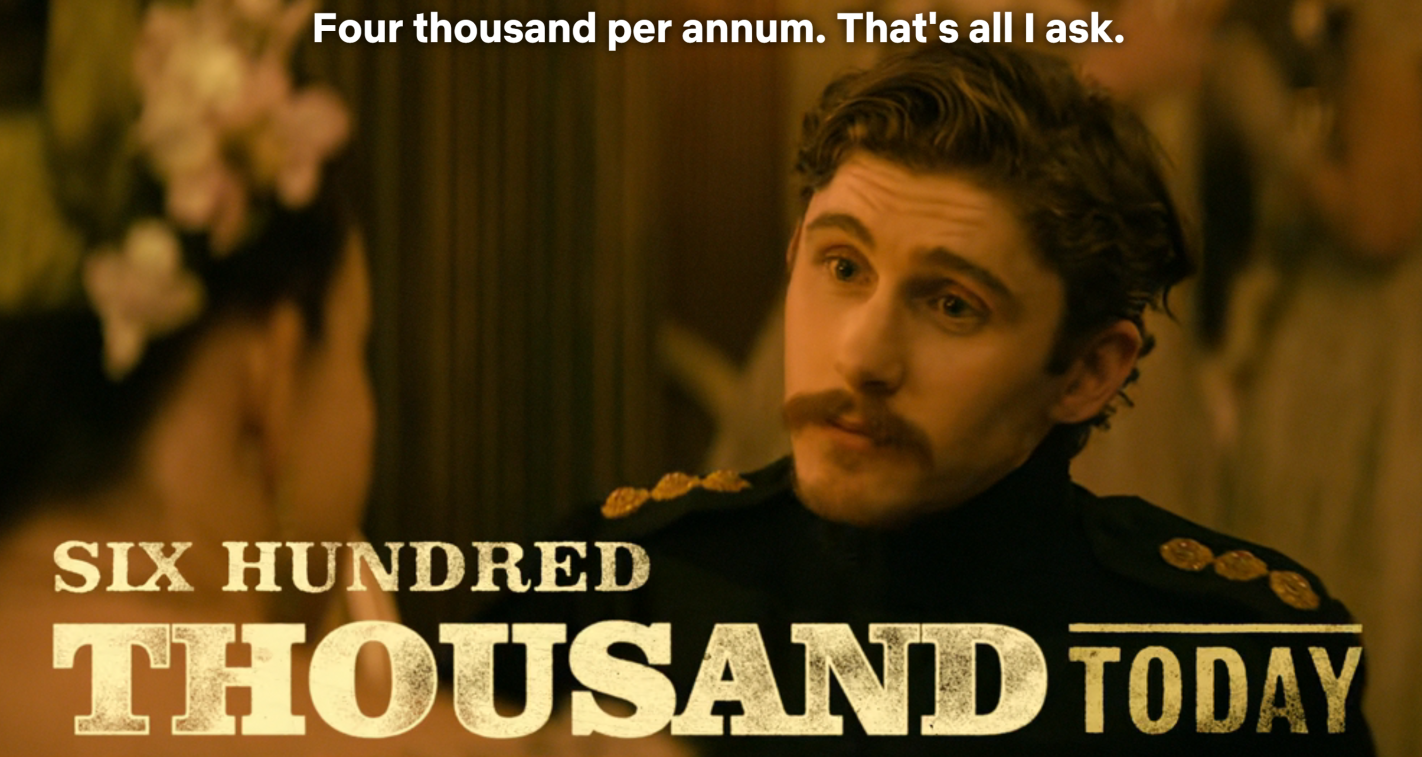

For example, in Episode 4 of the first season, one of the Guinness brothers is attempting to negotiate his annual payment from the family fortune. He asks for 4,000 pounds per year. On the screen the text flashes “Six Hundred Thousand Today.”

The creators of the show are to be commended for giving viewers some context, rather than leaving them baffled or pausing the show to Google it. But is 600,000 pounds today a good estimate? Where did they get this number? As with the “Gilded Age” estimate, it’s complicated, but it is probably more than you think.

Continue reading