In the first installment of this series on stock options, I focused on buying options, as a means to economically participate in the movement of a stock price up or down. If you guess correctly that say Apple stock will go up by 10% in the next two months, you can make much more money with less capital at risk by buying a call option than by buying Apple stock itself. Or if you guess correctly that Apple stock will go down by 10% in the next two months, you can make more money, with less risk, by buying a put option on Apple, then by selling the stock short.

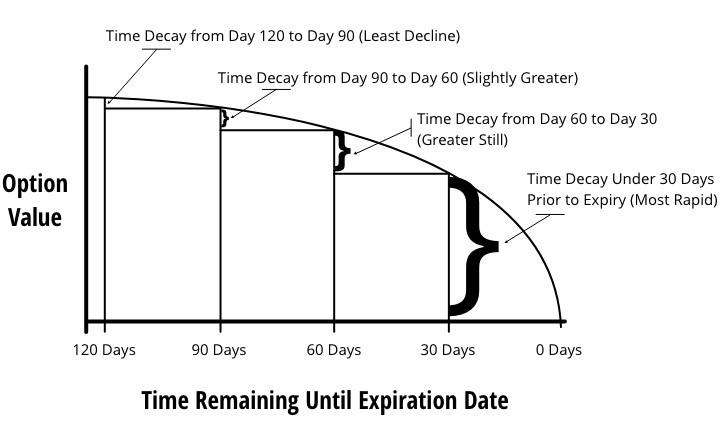

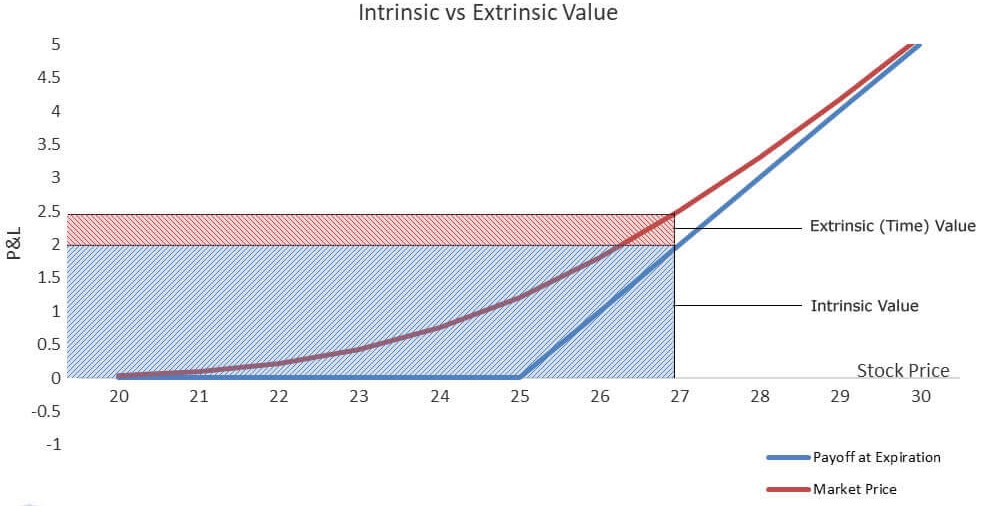

In part two of the series, I discussed how options are priced, noting the difference between intrinsic value, and the time-dependent extrinsic value.

Here in part three, I will discuss the merits of selling, rather than buying options. This is the way I usually employ them, and this is what I would suggest to others who want to dip their toes in this pond.

Just to revisit a point made in the first article, I see two distinct approaches to trading options. Professional option traders typically make hundreds of smallish trades a year, with the expectation that most of them will lose some money, but that some will make big money. A key to success here is limiting the size of the losses on your losing trades. It helps to have nerves of steel. Some people have the temperament to enjoy this process, but I do not.

Selling Out of the Money Calls

Instead if spending my days hunched over a screen managing lots of trades, I would rather set up a few trades which may run over the course of 6 to 12 months, where I am fairly OK with any possible outcome from the trades. A typical example is if I bought a stock at say $100 a share, and it has gone up to $110 a share, and I will be OK with getting $120 a share for it; in this case I might sell a six-month call option on it for five dollars, at a strike price of $115. The strike price here is $5 “out of the money”, i.e., $5 above the current market price.

There are basically two possible outcomes here. If the price of the stock goes above $115, the person who bought the call option will likely exercise it and force me to sell him or her the stock for a price of $115. Between that, and the five dollars I got for selling the option period, I will have my total take of $120.

On the other hand, if the stock price languishes below $115, I will get to keep the stock, plus the five dollars I got for selling the option. That is not a ton of money, but it is 4.3% of $115. If at the end of the first six-month period I turned around and sold another, similar six-month call option which had the same outcome, now I have squeezed an 8.6% income out of holding the stock. If the stock itself pays say a 4% dividend, now I am making 12.6% a year. Considering the broader stock market only goes up an average of around 10% a year, this is pretty good money.

At this point, you should be asking yourself, if making money selling options is so easy, I have I heard of this before? What’s the catch?

The big catch is that by selling this call, I have forfeited the chance to participate in any further upside of the stock price, beyond my $120 ($155 + $5). If at the end of six months, the stock has soared to $140 a share, but I must sell it for a net take of $120, I am relatively worse off by selling the call. I have still made some money ($20) versus my original purchase price. However, if I had simply held the stock without selling a call option, I would have been ahead by $40 instead of $20. And now if I want to stay in the game with this stock, I have to turn around and buy it back for $140. This decision can involve irksome soul-searching and regrets.

There are two techniques are used to reduce these potential regrets. One is to only sell calls on say half of my holdings of a particular stock. That way, if the stock rockets up, I have the consolation of making the full profit on half my shares.

The other technique is to try to identify stocks that trade in a range. For instance, the price of oil tends to load up and down between about seven day and $90 a barrel, barring some geopolitical upset. and the price of major oil companies, like Chevron or ExxonMobil, likewise trade up and down within a certain range. If you sell calls on these companies when they are near the top of their range, it is less likely that the share price will exceed the strike price of your option. Or, if it does, and you have to sell your shares, there is a good chance that if you just wait a few months, you will be able to buy them back cheaper. On the other hand, a stock like Microsoft tends to just go up and up and up, so it would not be a good target for selling calls.

Some Personal Examples

From memory, I will recount two cases from my own trading, with the two different outcomes noted above. ExxonMobil stock has been largely priced between $95 and $115 per share, depending mainly on the price of oil. In early 2024, with the price of XOM around 117, I sold a call contract with a strike price of 120 and an expiration date in January, 2024. I think I got around $9 per share for selling this option. The next twelve months went by, and the price of XOM never got above 120, so nobody exercised this call contract against me, and so I simply kept the $9, and kept my XOM shares. Since each contract covers 100 shares, I pocketed $9 x 100= $900 from this exercise, covering 100 shares (approx. $12,000 worth) of XOM stock.

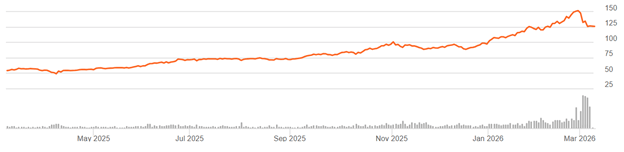

That was the good, here is a not so good: I bought some ARES (Ares Management Corporation) around February 2023 for (I think) around $80/share. For the next few months, the price wobbled between $75 and $90, while the broader S&P 500 stock index (lead by the big tech stocks) was rising smartly. I lost faith in ARES as a growth stock, but decided to at least squeeze some income out of it by selling a call option for about $10 at a strike price of $110 and a distant expiration of Dec 2024.

What then happened is ARES has taken off like a rocket, sitting today at $132/share. If it keeps up like this, it may be well over $150 by December, 2024. I will likely have to sell my 100 shares for $110 (the strike price), so I will get a total of $110 + $10 = $120 for my shares. That is far less than the current market value of these shares. I am not crying, though, since I have some more ARES shares that I did not sell calls on. Also, getting $120 for the shares I bought for $80 is OK with me. There is a saying on Wall Street about being too greedy, “Bulls make money, bears make money, pigs get slaughtered.”

Selling Puts

Briefly, selling out-of-the money puts is like selling calls, on the buy-side instead of the sell-side. It is a way to generate a little income, while garnering an advantageous purchase price, if things go as hoped. In my ARES example above, suppose my 100 shares get called away from me, when the market price is $150. I have various choices at that point. I could simply by a fresh 100 shares at $150, or I could get onto other investments. Or, if I were not happy about paying $150, I might sell a $140 put for say $6 per share. I would have to be OK with either of two outcomes: (1) either the price drops below $140 and the buyer of my put option forces me to buy it at $140 (in which case I need to have $140 x 100= $14,000 in cash available) , though net the stock will only cost me $140 – $6 = $134 ; or (2) the price stays above $140 and I simply pocket the $6 option premium. And I have to be willing to live with the regret if ARES goes on to $180, in which case it would have been better to have simply bought shares at $150 instead of dinking around with options.

So, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Again, I prefer to sell puts on companies that more trade in a range. For instance, gold tends to meander up and down – I have thought about it, but never got around to selling puts on gold companies at lows, and calls when they are high.

In Summary

I find judicious selling of calls and puts is a fairly tame way to make a little extra income on stocks. Also, it forces me to set some price targets for buying and selling. I have horrible selling discipline otherwise – I have a hard time making up my mind to buy a stock, but once I do, and once it goes up, I fall in love with it and don’t want to sell it (partly because lazy me doesn’t want to do the work to find a substitute). Selling calls is one way to force myself to set “OK” price targets for letting a stock go.

All that said, selling calls does forfeit participation in the full upside of a stock, and is probably not a good approach in general for growth-oriented tech stocks. Likewise, selling puts, instead of outright buying a stock, may lead to regrets if the stock price goes way up and gets away from you.

As usual, this discussion does not constitute advice to buy or sell any security.