Tax holidays are when some set of goods are tax-free for a period of time. These might be back-to-school supplies for a week or a weekend, or hurricane supplies for several months. These policies tend to be popular among non-economists.

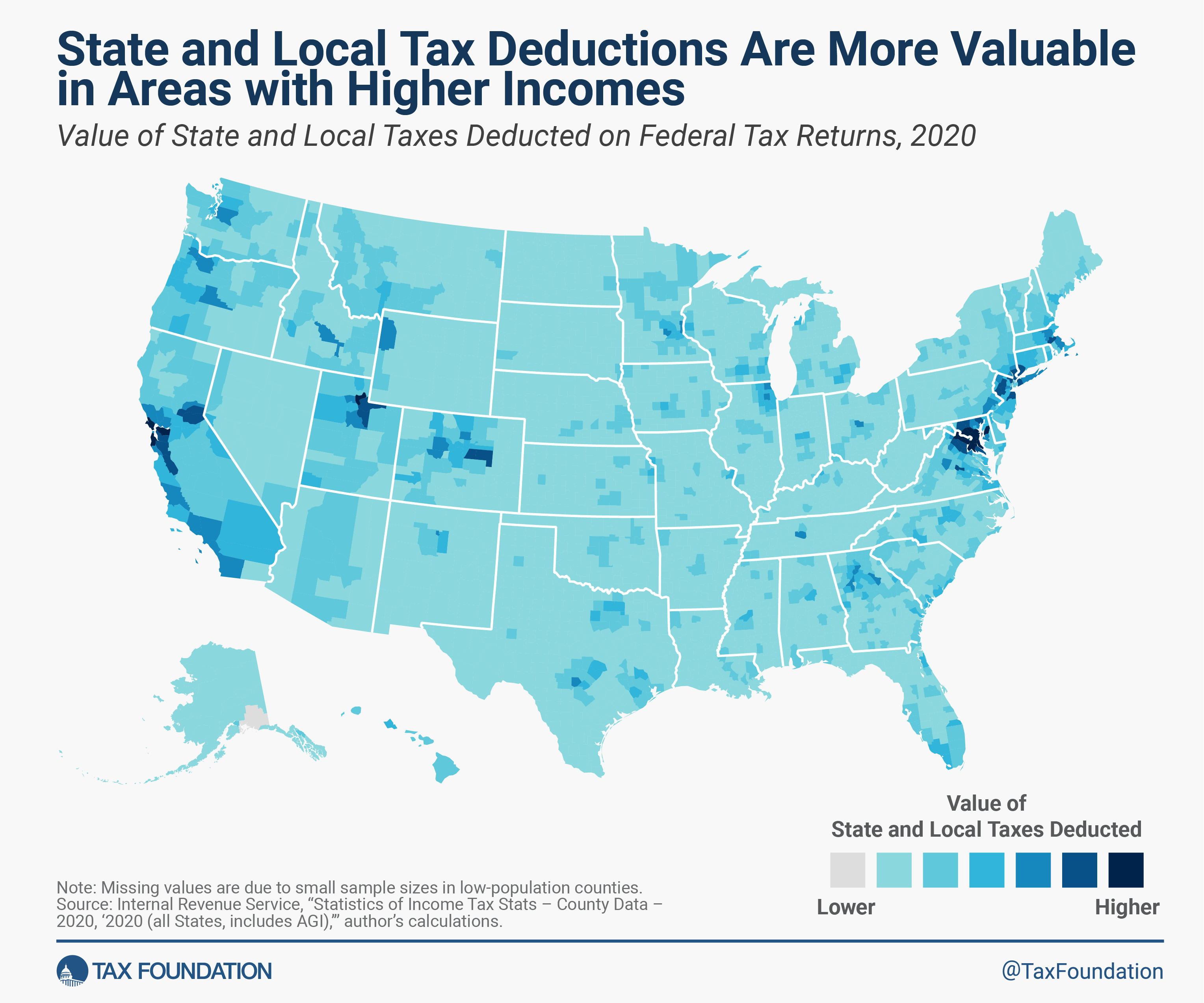

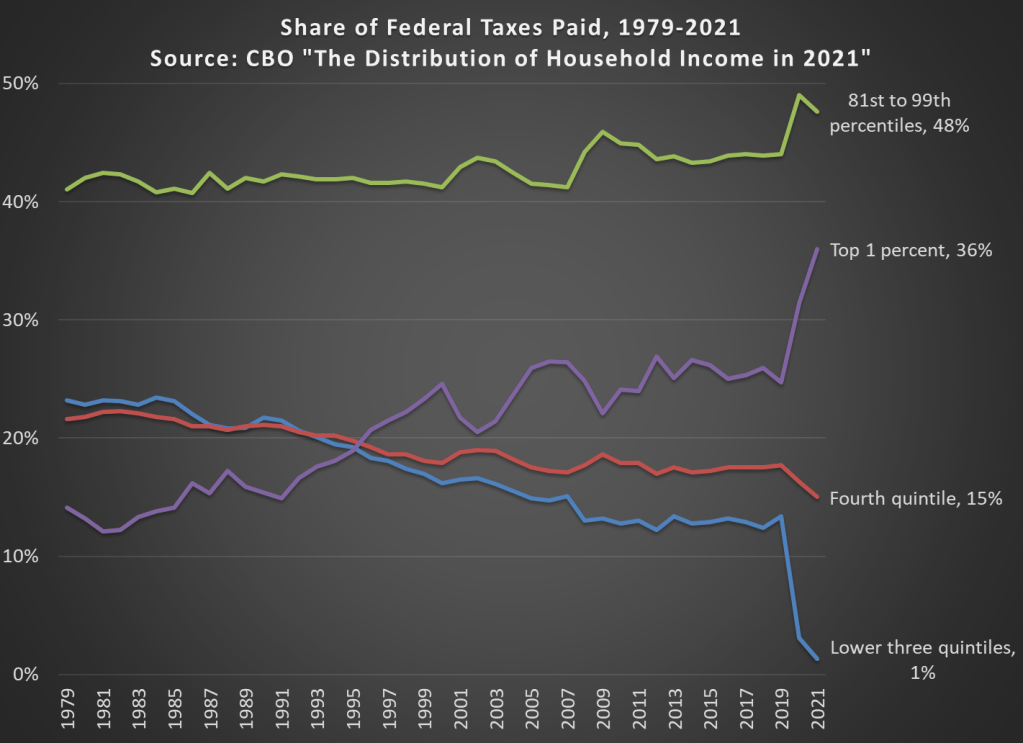

There are practical reasons for anyone to decry tax holidays. Usually, there is a particular type of good that qualify for tax-free status. These are often selected politically rather than by an informed and reasoned way with tradeoffs in mind. Sometimes, there is a subpopulation that is intended to benefit. However, the entire population gets the tax holiday and those with the most resources, who often have higher incomes, are best able to adjust their consumption allocations and enjoy the biggest benefits. A tax holiday weekend is no good to a single-mom who can’t get off work during that time.

Getting more economic logic, these holidays also concentrate shopping on the tax-free days, causing traffic and long lines that eat away at people’s valuable time – even if they aren’t purchasing the tax-free items. Furthermore, retailers must comply with the law. This means ensuring that all items are taxed correctly, making neither mistakes in over-taxing or under-taxing. Given the variety of goods and services out there, this is a large cost for individual firms.

Finally, as economists know, there is a deadweight loss anytime that there is a tax. As a consequence, you might think that economists would love anytime that taxes are low. But, holding total tax revenue constant, a tax break on a tax holiday implies that there must be greater tax revenues on the other non-holidays. In particular, economists also know that losses in welfare increase quadratically with changes in tax rates. Therefore, higher tax rates on some days and lower rates on other days causes more welfare loss than if the tax rate had been uniform the entire time. In the current context, such welfare loss manifests as forgone beneficial transactions. These non-transactions are hard for non-economists to understand because we can’t see purchases that don’t happen, but would have happened in the absence of poor policy.

Let’s look at some graphs.

Continue reading