62 weeks. That’s how long the median male worker would need to work in a year to support a family in 2022, according to the calculations of Oren Cass for the American Compass Cost-of-Thriving Index released this year. Not only is 62 weeks longer than the baseline year of 1985 (when it took about 40 weeks, according to COTI), but there is a big problem: there aren’t 62 weeks in year. It is, by this calculation, impossible for a single male earner to support a family.

Is this true? In our new AEI paper, Scott Winship and I strongly disagree. First, we challenge the 62-week figure. With a few reasonable corrections to Cass’ COTI, we show that it is indeed possible for a median male earner to support a family. It takes 42 weeks, not 62 as reported in COTI.

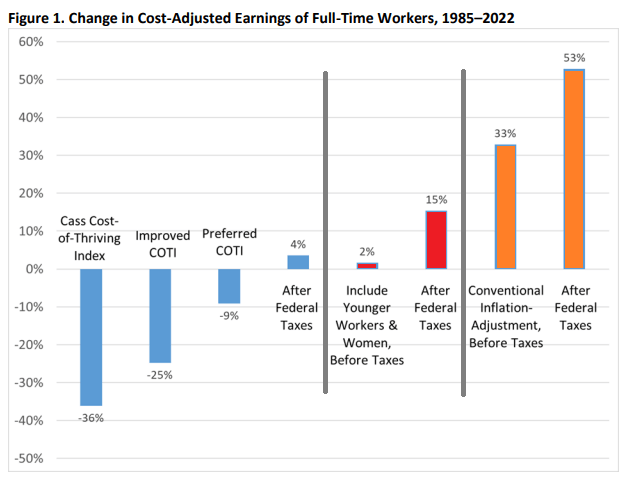

But wait, there’s more. Much more. In our paper, we provide a range of reasonable estimates for how the cost of thriving has changed since 1985. In the COTI calculation, the standard of living for a single-earner family has fallen by 36 percent since 1985. In our most optimistic estimate, the standard of living has risen by 53 percent. The chart below summarizes our various alternative versions of COTI. How do we get such radically different results? Is this all a numbers game?

To that second question, we say “no,” this isn’t a game. There is a correct numerical representation of reality, and we make the case that our interpretation better represents that single-earner family. But even if you don’t agree with our most optimistic estimate, there are serious errors and omissions from COTI that make it fundamentally flawed. At a minimum, we argue that it is easier, perhaps only slightly easier, for a single-earner male to support a family than in 1985. One of the major omissions is failing to consider the changes in federal income taxes since 1985 for families.

Cass considers five consumer expenditure categories: groceries, housing, health care, transportation, and education. But COTI excludes a sixth important category: taxes. Importantly, a single-earner family with children will pay almost the same amount in federal taxes as in 1985 in nominal terms. That means as a percent of their income, they pay a lot less: just 3 weeks of annual earnings in 2022, compared with 8.5 weeks in 1985. This calculation includes payroll taxes. The biggest change in tax policy relevant to this family is the introduction and expansion of the Child Tax Credit. While there is much debate today about what should be done with the CTC moving forward, any comparison of family expenditures today compared with a generation ago must take account of this and other tax changes.

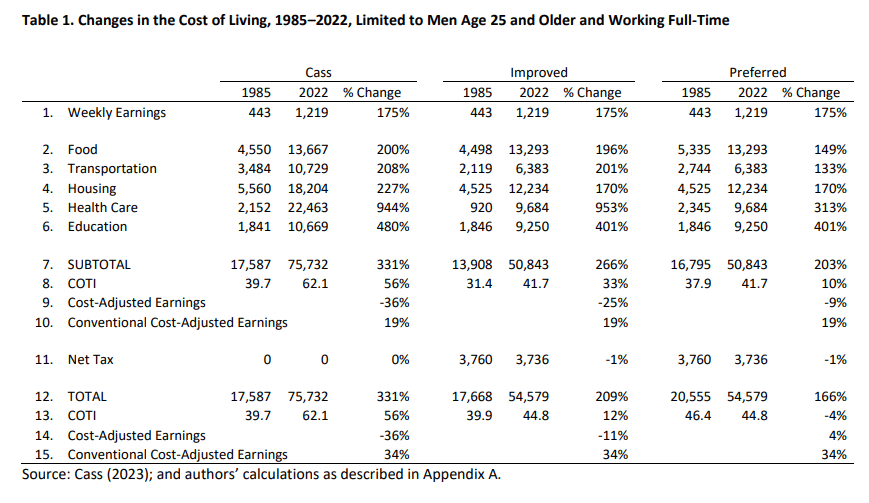

Aside from the omission of income taxes, what are the major errors of COTI? We find errors in all five of the COTI spending categories, but some are more important than others. Our changes are summarized in the table below (these match up to the blue bars in the chart above)

Health care is a big one. While the economics and politics of US health care are an on-going political football and headache, Cass vastly overstates the cost to a typical family. The major error: he includes both the employer and employee portions of the cost of health insurance in his calculation. But the employer costs aren’t subtracted from wages. So instead of 18 weeks of earnings to buy health insurance, it takes about 8 weeks. This is indeed a big increase from 1985, but Cass vastly overstates the cost by making a very basic error.

Housing cost are another big error. While housing costs have indeed increased, and we agree that major reforms are needed to increase the supply of housing, COTI still overstates the increase. COTI says it takes 15 weeks of earnings to pay for housing. We say it is more like 10 weeks of earnings. The major error? COTI only considers the cost of renting. Renters are important, but they are only about one-third of the market. By including reasonable cost estimates for the two-thirds of Americans that own their homes, we show that Cass overestimates the cost by about 50 percent in 2022. This is a major error. US housing policy is indeed in need of reform, and calculating costs for this category is very challenging given the wide variation in costs across the country, but our research shows that COTI also gets this figure wrong.

We have many other important as well as minor corrections to the COTI data in our paper, but what is the bottom line? We present two alternative versions of COTI. The current version of COTI from American Compass suggests that the number of weeks of work needed by a single-earner male family have rose from 40 weeks in 1985 to 62 weeks in 2022 – again, this is not only a big increase, but mathematically impossible to achieve given that there are only 52 weeks in a year.

The first alternative version we present corrects for some basic errors (such as the health care and housing errors we discussed) and includes the effect of federal taxes. In this version, there is still an increase in the number of weeks, from about 40 to 45 weeks, but notice two things. First, the increase is smaller. But second, 45 weeks is clearly possible within a 52-week year. One might object that it is still harder to thrive, but if you accept our corrections, at a minimum you must acknowledge that it is still possible to support a family on one male income.

But our paper goes farther. We make further changes to the costs from COTI. Not merely errors that we identify, but changes in judgement that we think are important too. For example, we argue that, properly considered, the price of groceries has increase slower than median male earnings since 1985. In COTI, grocery prices have increased faster than wages. We use the Consumer Price Index as our baseline for comparison in this extended calculation, rather than the estimates from Cass. We include slight modifications for almost all of the cost estimates in our preferred calculation in the paper.

What’s the bottom line? We find that it is actually easier for a single-earner male family to support a family than 1985, falling from about 46.4 to 44.8 weeks of work. It’s both possible and easier. You might object that this is only a small improvement. OK. But our analysis completely turns COTI on its head. And keep in mind that this is only for the five categories Cass has chosen. He has excluded most consumer goods, all of which have gotten much cheaper. Families were buying TVs in 1985, and they are buying TVs today. They are much cheaper, even without adjusting for quality improvements. With the adjustments, they are extremely cheaper. Repeat this for dozens of consumer goods excluded from COTI.

Finally, there is one more major way that we think COTI is flawed. Focusing on families with a single male earner is just wrong-headed. More families have two earners today, yes, but including them in the analysis is not cheating. These families have more income! They will have some additional expenses, such as childcare, but you could reasonably include this in the calculation if you wanted to make such a comparison (and compared to family incomes, I have previously shown that there hasn’t been an increase in the costs of raising a child). And more families today have single earner that are female, and female earnings have increased more than male earnings over this time period: about 30 percent of females since 1985 (inflation adjusted, median full-time workers), compared to just 5 percent for males. Focusing narrowly on the traditional male-headed, single-earner families misses the complexity of families and the workforce that is now part of our modern world.

4 thoughts on “The American Family Is Thriving, Even if They Only Have One Male Earner (But Most Don’t)”