The average price of a dozen eggs is back up over $4, about the same as it was 2 years ago during the last avian flu outbreak. Egg prices are up 65% in the past year. But does that mean the grocery inflation we experienced in 2021-22 is roaring back?

No really. Spending on eggs is around 0.1% of all consumer spending, and just about 2% of consumer spending on groceries. Symbolically, it may be important, since consumers pick up a dozen eggs on most shopping trips. But to know what’s going on with groceries overall, we have to look at the other 98% of grocery spending.

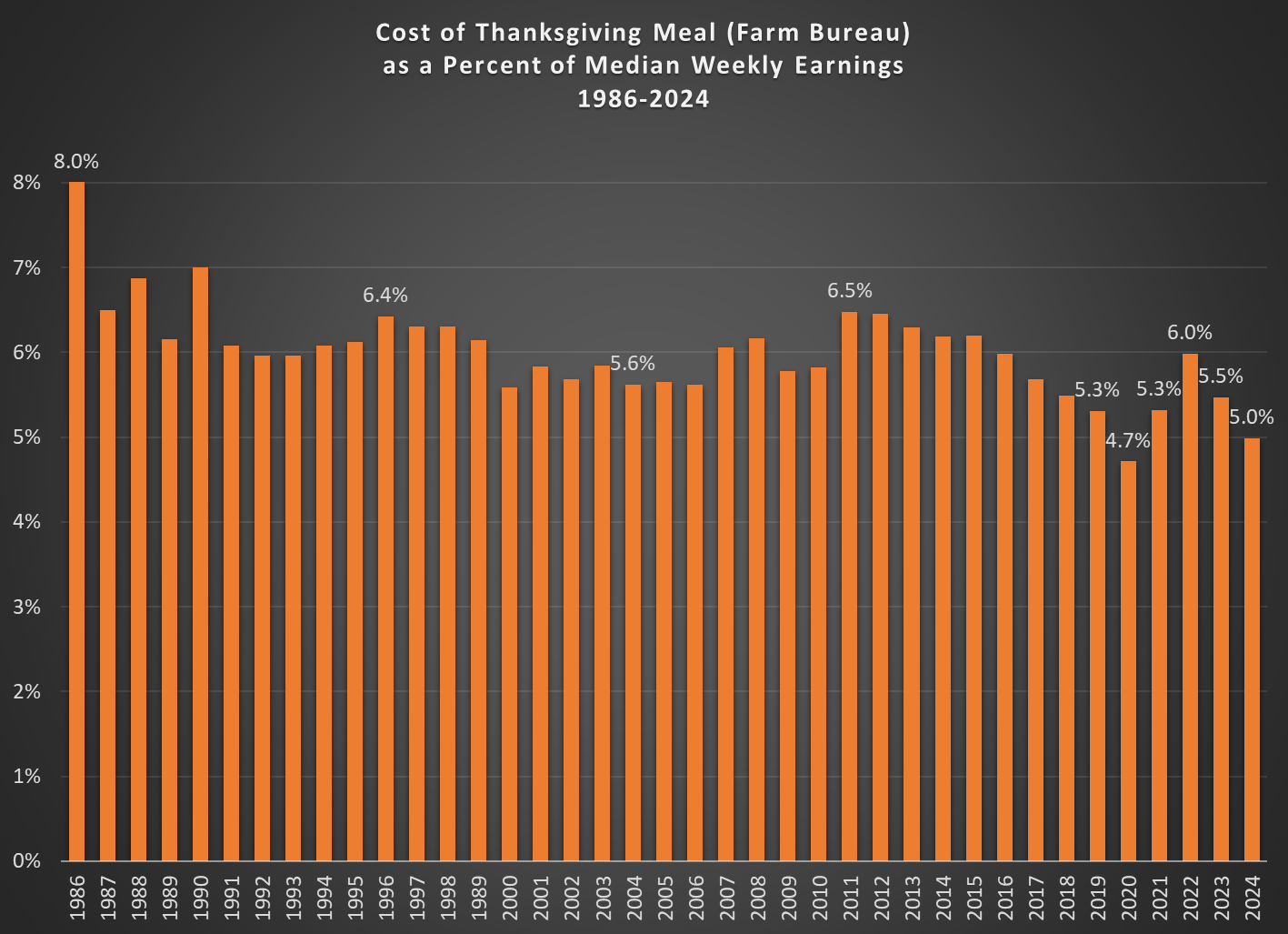

It’s been a wild 4 years for grocery prices in the US. In the first two years of the Biden administration, grocery prices soared over 19%. But in the second two years, they are up just 3% — pretty close to the decade average before the pandemic (even including a few years with grocery deflation!).

As any consumer will tell you, just because the rate of inflation has fallen doesn’t mean prices on average have fallen. Prices are almost universally higher than 4 years ago, but you can find plenty of grocery items that are cheaper (in nominal terms!) than 1 or 2 years ago: spaghetti, white bread, cookies, pork chops, chicken legs, milk, cheddar cheese, bananas, and strawberries, just to name a few (using BLS average price data).

There is no way to know the future trajectory of grocery prices, and we have certainly seen recent periods with large spikes in prices: in addition to 2021-22, the US had high grocery inflation in 2007-2009, 1988-1990, and almost all of the period from 1972-1982 (two-year grocery inflation was 37% in 1973-74!). Undoubtedly grocery prices will rise again. But the welcome long-run trend is that wages, on average, have increased much faster than grocery prices: