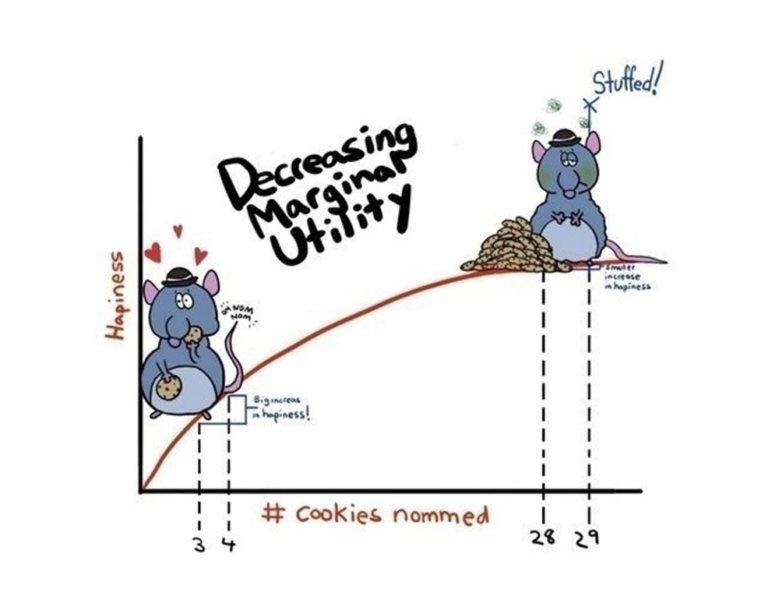

I made this Decreasing Marginal Utility rat picture when I was an undergraduate, and it caught on. A textbook asked me for permission to print it.

This week on Twitter (X.com), someone said it was their favorite graph. Upon replying I learned that he had used it for teaching. It’s fun when you know one of your ideas is out in the world helping people.

For real? I absolutely HOWLED when I found it on a google image search! Bravo! I taught HS Econ for many years and this was the kind of stuff that kept kids awake!

https://twitter.com/arburnside/status/1702690454884487495

Blogger privilege is to manifest a new conversation on here. If one of my research articles were to achieve the same level of influence as the stuffed rat, then people might tweet something along the following lines:

“An Experiment on Protecting Intellectual Property,” (2014), with Bart Wilson. Experimental Economics, 17:4, 691-716.

This original project, both in terms of methodology and subject, is one of the first controlled experiments on intellectual property protection, which has inspired subsequent lab work on this issue. We present a color cube mechanism that provides a creative task for subjects to do in an experiment on creative output. The results indicate that IP protection alone does not cause people to become inventors, although entrepreneurs are encouraged to specialize by IP protection.

“Smile, Dictator, You’re On Camera,” (2017), with Matthew McMahon, Matthew Simpson and Bart Wilson. Southern Economic Journal, 84:1, 52-65.

The dictator game (DG) is attractive because of its simplicity. Out of thousands of replications of the DG, ours is probably the controlled experiment that has reduced “social distance” to the farthest extreme possible, while maintaining the key element of anonymity between the dictator and their receiver counterpart. In our experiment the dictator knows they are being watched, which is the opposite of the famous “double-blind” manipulation that removed even the view of the experimenter. As we predicted, people are more generous when they are being watched. Anyone teaching about DGs in the classroom should show our entertaining video of dictators making decisions in public: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZHN8xyp6Y0&t=22s

“My Reference Point, Not Yours,” (2020) Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 171: 297-311.

There is a lot of talk about reference points. No matter how you feel about “behavioral” economics, I don’t think anyone would deny that reference-dependent behavior explains some choices, even very big ones like when to sell your house. Considering how important reference points are, can people conceive of the fact that different people have different reference points shaped by their different life experiences? Results of this study imply that I tend to assume that everyone else has my own reference point, which biases my beliefs about what others will do. Because this paper is short and simple, it would make a good assignment for students in either an experimental or econometrics class. I have a blog post on how to turn this paper into an assignment for students who are just learning about regression for the first time.

“If Wages Fell During a Recession,” (2022) with Daniel Houser, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. Vol. 200, 1141-1159.

The title comes from Truman Bewley’s book Why Wages Don’t Fall during a Recession. First, I’ll take some lines directly from his book summary:

A deep question in economics is why wages and salaries don’t fall during recessions. This is not true of other prices, which adjust relatively quickly to reflect changes in demand and supply. Although economists have posited many theories to account for wage rigidity, none is satisfactory. Eschewing “top-down” theorizing, Truman Bewley explored the puzzle by interviewing—during the recession of the early 1990s—over three hundred business executives and labor leaders as well as professional recruiters and advisors to the unemployed.

By taking this approach, gaining the confidence of his interlocutors and asking them detailed questions in a nonstructured way, he was able to uncover empirically the circumstances that give rise to wage rigidity. He found that the executives were averse to cutting wages of either current employees or new hires, even during the economic downturn when demand for their products fell sharply. They believed that cutting wages would hurt morale, which they felt was critical in gaining the cooperation of their employees and in convincing them to internalize the managers’ objectives for the company.

We are one of the first to take this important question to the laboratory. The nice thing about an experiment is that you can measure shirking precisely and you can get observations on wage cuts, which are rare in the naturally occurring American economy.

We find support for the morale theory, but a new puzzle got introduced along the way. Many of our subjects in the role of the employer cut the wages of their counterpart, which probably lowered their payment. Why didn’t they anticipate the retaliation against wage cuts? That question inspired the paper “My Reference Point, Not Yours.”

“Other people’s money: preferences for equality in groups,” (2022) with Gavin Roberts, European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 73.

Andreoni & Miller (2002) have been cited over 2500 times for their experiment that shows demand curves for altruism slope down. Economic theory is not broken by generosity. We extend their work to show that demand curves for equality slope down. Individuals don’t love inequality, but they also don’t love parting with their own money. There is a higher demand for reducing inequality with other people’s money than with own income.

“Willingness to be Paid: Who Trains for Tech Jobs?” (2022), Labour Economics, Vol 79, 102267.

This is the last paper I’ll do here. At this point, readers probably would like a funny animal picture. Here’s a meme about the difficult life of computer programmers:

For decades, tech skills have had a high return in the labor market. There is very little empirical work on why more people do not try to become computer programmers, although there are policy discussions about confidence and encouragement.

I ran an experiment to measure something that is important and underexplored. One thing I found is that attempts to increase confidence, if not carefully evaluated, might backfire.

Would you predict it’s more important to have taken a class in programming or for a potential worker to report that they enjoy programming? My results imply that we should be doing more to understand both the causes and effects of subjective preferences (enjoyment) for tech work.

A few more decades to go here… I will try to top the stuffed rat picture.