Watch it here. It is fantastic:

Economics

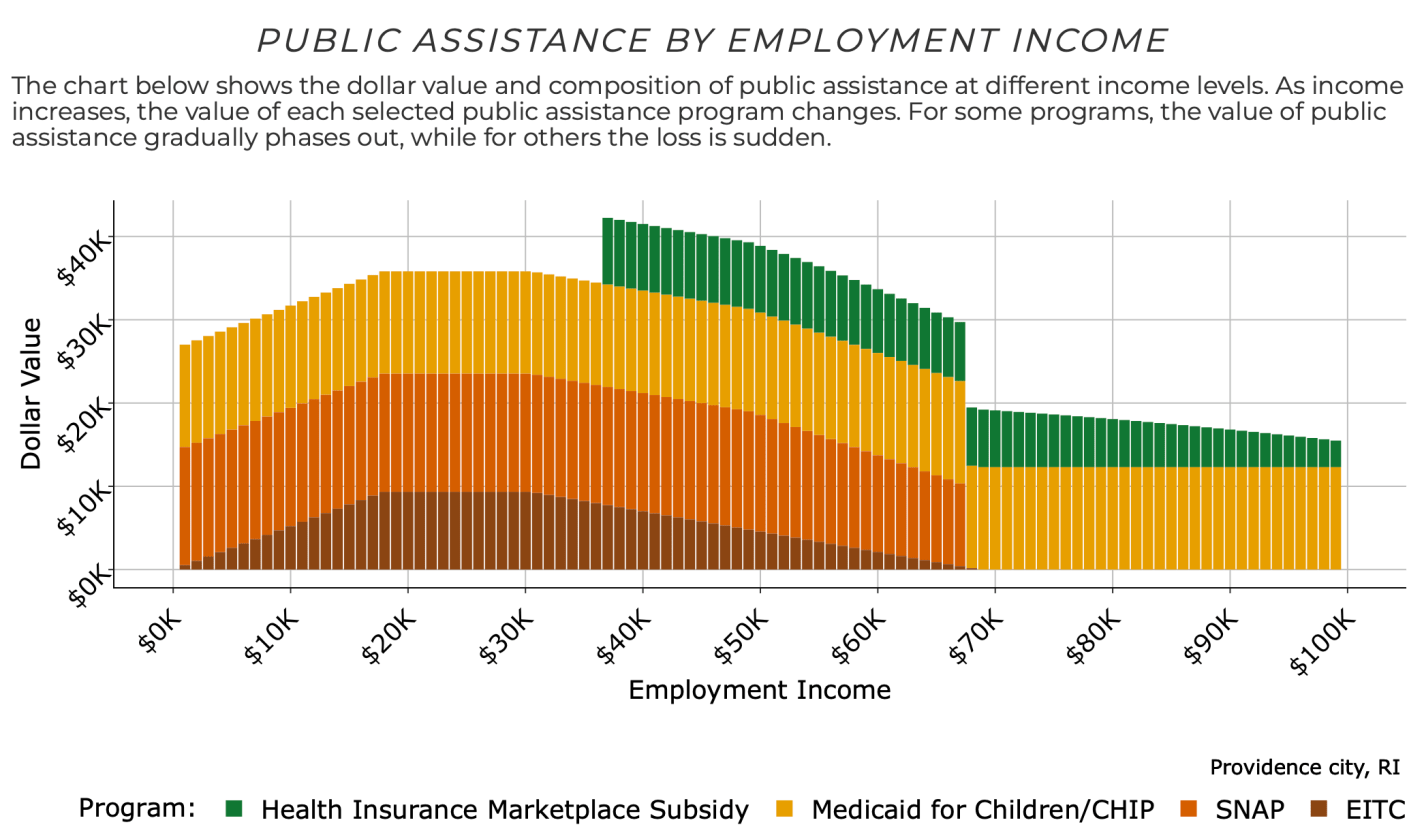

Benefit Cliff Data

I said years ago on my Ideas Page that we need data and research on Benefit Cliffs:

Benefits Cliffs: Implicit marginal tax rates sometimes go over 100% when you consider lost subsidies as well as higher taxes. This could be trapping many people in poverty, but we don’t have a good idea of how many, because so many of the relevant subsidies operate at the state and local level. Descriptive work cataloging where all these “benefits cliffs” are and how many people they effect would be hugely valuable. You could also study how people react to benefits cliffs using the data we do have.

But it turns out* that the Atlanta Fed has now done the big project I’d hoped some big institution would take on and put together the data on benefits cliffs. They even share it with an easy-to-use tool that lets you see how this applies to your own family. Based on your family’s location, size, ages, assets, and expenses, you can see how the amount of public assistance you are eligible for varies with your income:

Then see how your labor income plus public assistance changes how well off you are in terms of real resources as your labor income rises:

For a family like mine with 3 kids and 2 married adults in Providence, Rhode Island, it shows a benefit cliff at $67,000 per year. The family suddenly loses access to SNAP benefits as their labor income goes over $67k, making them worse off than before their raise unless their labor income goes up to at least $83,000 per year.

I’ve long been concerned that cliffs like this in poorly designed welfare programs will trap people in (or near) poverty, where they avoid taking a job, or working more hours, or going for a promotion, or getting married, in order to protect their benefits. This makes economic sense for them over a 1-year horizon but could keep them from climbing to independence and the middle-class in the longer run. You can certainly find anecdotes to this effect, but it has been hard to measure how important the problem is overall given the complex interconnections between federal, state, and local programs and family circumstances.

I look forward to seeing the research that will be enabled by the full database that the Atlanta Fed has put together, and I’m updating my ideas page to reflect this.

*I found out about this database from Jeremy’s post yesterday. Mentioning it again today might seem redundant, but I didn’t want this amazing tool to get overlooked for being shared toward the bottom of a long post that is mainly about why another blogger is wrong. I do love Jeremy’s original post, it takes me back to the 2010-era glory days of the blogosphere that often featured long back-and-forth debates. Jeremy is obviously right on the numbers, but if there is value in Green’s post, it is highlighting the importance of what he calls the “Valley of Death” and what we call benefit cliffs. The valley may not be as wide as Green says it is and it may be old news to professional tax economists, but I still think it is a major problem, and one that could be fixed with smarter benefit designs if it became recognized as such.

Poverty Lines Are Hard to Define, But Wherever You Set Them Americans Are Moving Up (And The “Valley of Death” is Less Important Than You Think)

Last week I wrote a fairly long post in response to an essay by Michael Green. His essay attempted to redefine the poverty line in the US, by his favored calculation up to $140,000 for a family of four. That $140,000 number caught fire, being covered across not only social media and blogs, but in prominent places such as CNN and the Washington Post. That $140,000 number was key to all of the headlines. It grabbed attention and it got attention. So it’s useful to devote another post this week to the topic.

And Mr. Green has written a follow-up post, so we have something new to respond to. Mr. Green has also said a lot of things on Twitter, but Twitter can be a place for testing out ideas, so I will mostly stick to what he posted on Substack as his complete thoughts. I am also called out by name in his Part 2 post, so that’s another reason to respond (even though he did not respond directly to anything I said).

Once again, I’ll have 3 areas of contention with Mr. Green:

- As with last week, I maintain that $140,000 is way too high for a poverty line representing the US as a whole (and Mr. Green seems to agree with this now, even though $140,000 was the headline in all of the major media coverage)

- There are already existing alternative measures of what he is trying to grasp (people above the official poverty line but still struggling), such as United Way’s ALICE, or using a higher threshold of the poverty rate (Census has a 200% multiple we can easily access)

- His idea of the “Valley of Death” is already well-covered by existing analyses of Effective Marginal Tax Rates, and tax and benefit cliffs. This isn’t to say that more attention is warranted, but Mr. Green doesn’t need to start his analysis from scratch. And this “Valley” is probably narrower than he thinks.

Structure Integrated Panels (SIP): The Latest, Greatest (?) Home Construction Method

Last week I drove an hour south to help an acquaintance with constructing his retirement home. I answered a group email request, looking for help in putting up a wall in this house.

I assumed this was a conventional stick-built construction, so I envisioned constructing a studded wall out of two by fours and two by sixes whilst lying flat on the ground, and then needing four or five guys to swing this wall up to a vertical position, like an old-fashioned barn raising.

But that wasn’t it at all. This house was being built from Structure Integrated Panels (SIP). These panels have a styrofoam core, around 5 inches thick, with a facing on each side of thin oriented strandboard (OSB). (OSB is a kind of cheapo plywood).

The edges have a sort of tongue and groove configuration, so they mesh together. Each of the SIP panels was about 9 feet high and between 2 feet and 8 feet long. Two strong guys could manhandle a panel into position. Along the edge of the floor, 2×6’s had been mounted to guide the positioning of the bottom of each wall panel.

We put glue and sealing caulk on the edges to stick them together, and drove 7-inch-long screws through the edges after they were in place, and also a series of nails through the OSB edges into the 2×6’s at the bottom. Pneumatic nail guns give such a satisfying “thunk” with each trigger pull, you feel quite empowered. Here are a couple photos from that day:

The homeowner told me that he learned about SIP construction from an exhibit in Washington, DC that he attended with his grandson. The exhibit was on building techniques through the ages, starting with mud huts, and ending with SIP as the latest technique. That inspired him.

(As an old guy, I was not of much use lifting the panels. I did drive in some nails and screws. I was not initially aware of the glue/caulk along the edges, so I spent my first 20 minutes on the job wiping off the sticky goo I got all over my gloves and coat when I grabbed my first panel. My chief contribution that day was to keep a guy from toppling backwards off a stepladder who was lifting a heavy panel beam overhead).

We amateurs were pretty slow, but I could see that a practiced crew could go slap slap slap and erect all the exterior walls of a medium sized single-story house in a day or two, without needing advanced carpentry skills. Those walls would come complete with insulation. They would still need weatherproof exterior siding (e.g. vinyl or faux stone) on the outside, and sheetrock on the inside. Holes were pre-drilled in the Styrofoam for running the electrical wiring up through the SIPs.

From my limited reading, it seems that the biggest single advantage of SIP construction is quick on-site assembly. It is ideal for situations where you only have a limited time window for construction, or in an isolated or affluent area where site labor is very expensive and hard to obtain (e.g., a ski resort town). Reportedly, SIP buildings are mechanically stronger than stick-built, handy in case of earthquakes or hurricanes. Also, an SIP wall has very high insulation value, and the construction method is practically airtight.

SIP construction is not cheaper than stick built. It’s around 10% more expensive. You need perfect communication with the manufacturer of the SIP panels; if the delivered panels don’t fit properly on-site, you are hosed. Also, it is tough to modify an SIP house once it is built.

Because it is so airtight, it requires some finesse in designing the HVAC system. You need to be very careful protecting it from the walls from moisture, both inside and out, since the SIP panels can lose strength if they get wet. For that reason, some folks prefer to not use SIP for roofs, but only for walls and first-story flooring.

For more on SIP pros and cons, see here and here.

The Poverty Line is Not $140,000

UPDATE: Michael Green has written a follow-up post which essentially agrees that $140,000 is not a good national poverty line, but he still has concerns. I have written a new response to his post.

A recent essay by Michael W. Green makes a very bold claim that the poverty line should not be where it is currently set — about $31,200 for a family of four — but should be much higher. He suggests somewhere around $140,000. The essay was originally posted on his Substack, but has now gone somewhat viral and has been reposted at the Free Press. (Note: that actual poverty threshold for a family of four with two kids is $31,812 — a minor difference from Mr. Green’s figure, so not worth dwelling on much, but this is a constant frustration in his essay: he rarely tells us where his numbers come from.)

I think there are at least three major errors Mr. Green makes in the essay:

- He drastically underestimates how much income American families have.

- He drastically overstates how much spending is necessary to support a family, because he uses average spending figures and treats them as minimum amounts.

- He obsesses over the Official Poverty Measure, since it was originally based on the cost of food in the 1960s, and ignores that Census already has a new poverty measure which takes into account food, shelter, clothing, and utility costs: the Supplement Poverty Measure.

I won’t go into great detail about the Official Poverty Measure, as I would recommend you read Scott Winship on this topic. Needless to say, today the OPM (or some multiple of it) is primarily used today for anti-poverty program qualification, not to actually measure how well families are doing today. If we really bumped the Poverty Line about to $140,000, tons of Americans would now qualify for things like Medicaid, SNAP, and federal housing assistance. Does Mr. Green really want 2/3 of Americans to qualify for these programs? I doubt it. Instead, he seems to be interested in measuring how well-off American families are today. So am I.

Let’s dive into the numbers.

Continue readingWhat Tariffs Mean For Your Finances

That’s the title of a talk I’ll be giving Saturday at the Financial Capability Conference at Rhode Island College. Registration for the conference, which also features personal finance speakers and top Rhode Island politicians, is free here.

A preview: after many changes, the average tariff on the goods Americans import has settled in the 15-20% range:

If the tariffs stay in place, which is far from certain, this will represent roughly a 2% increase in overall costs for Americans (a ~17% tax on imports which are ~14% of the economy predicts a 2.4% increase, but a bit of that will be paid by foreign producers lowering prices).

This is bad for US consumers, but not as bad as the Covid-era inflation, and likely not as bad as our upcoming problems with debt and plans to weaken the dollar. It is more valuable for most people to make sure they are getting the personal finance basics right than to think about how to avoid tariffs, though they may want to consider investments that hold their value with a weakening dollar.

The Return of Data

Tomorrow, the Bureau of Labor Statistics is set to release the first major report of economic data that was delayed by the federal government shutdown: the September 2025 employment situation report. It’s good that we will get that information, but notice that we’re now in the middle of November and we’re just now learning what the unemployment rate was in the middle of September — 2 months ago (you can see their evolving updated release calendar at this link). This is less than ideal for many reasons, including that the Federal Reserve is trying to make policy decisions with a limited amount of the normal data.

What about the October 2025 unemployment rate? Early indications from the White House are that we just will never know that number. Why? Because the data likely wasn’t collected, due to the federal government shutdown. There was some confusion about this recently, with many people asking why they don’t just release it. Well, that’s because they can’t release what they don’t collect: the unemployment rate comes from the Current Population Survey, a joint effort of the BLS and Census where they interview 60,000 households every month. The survey was not done in October. It would not be impossible to do this retroactively, but the data would be of lower quality and, again, quite delayed. That gap in a series that goes back to 1948 wouldn’t be the end of the world, but it is symbolic of the disfunction of our current political moment.

What about GDP? We are now over half way through the 4th quarter of the year, and… we still don’t know what happened with GDP in the third quarter of 2025. BEA is in the process of revised their release calendar too, but they haven’t yet told us when 3rd quarter GDP will be released. In this case, the data was likely collected, but there is a certain amount of processing that needs to be done. Sure, we have estimates from places like the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model, but the trouble is… many of the inputs it uses are government data which haven’t been released yet for the last month of the quarter.

Eventually, all will mostly be well and back to normal, even if there are a few monthly gaps in some data series. The temporary data darkness may be coming to an end soon, but I fear it will not be the last time this happens.

“Big Short” Michael Burry Closes Scion Hedge Fund: “Value” Approach Ceased to Add Value?

Michael Burry is famed for being among the first to both discern and heavily trade on the ridiculousness of subprime mortgages circa 2007. He is a quirky guy: brilliant, but probably Asperger‘s. That comes through in his portrayal in the 2015 movie based on the book, The Big Short.

He called it right with mortgages in 2007, but was early on his call, and for many months lost money on the bold trading positions he had put on in his hedge fund, Scion Capital. Investors in his fund rebelled, though he eventually prevailed. Reportedly he made $100 million himself, and another 700 million for his investors, but in the wake of this turmoil, he shut down Scion Capital.

In 2013 he reopened his hedge fund under the name Scion Asset Management. He has generated headlines in the past several years, criticizing high valuations of big tech companies. Disclosure of his short positions on Nvidia and Palantir may have contributed to a short-term decline in those stocks. He has called out big tech companies in general for stretching out the schedule of depreciation of their AI data center investments, to make their earnings look bigger than they really are.

Burry is something of an investing legend, but people always like to take pot shots at such legends. Burry has been rather a permabear, and of course they are right on occasion. For instance, I ran across the following OP at Reddit:

Michael burry is a clown who got lucky once

I am getting sick and tired of seeing a new headline or YouTube video about Michael burry betting against the market or shorting this or that.

First of all the guy is been betting against the market all his career and happened to get lucky once. Even a broken clock is right twice in a day. He is one of these goons who reads and understands academia economics and tries to apply them to real world which is they don’t work %99 of the time. In fact guys like him with heavy focus on academia economic approach don’t make it to far in this industry and if burry didn’t get so lucky with his CDS trade he would be most likely ended up teaching some bs economic class in some mid level university.

Teaching econ at some mid-level university, ouch. (But a reader fired back at this OP: OP eating hot pockets in his moms basement criticizing a dude who has made hundreds of millions of dollars and started from scratch.)

Anyway, Burry raised eyebrows at the end of October, when he announced that he was shutting down his Scion Asset Management hedge fund. This Oct 27 announcement was accompanied by verbiage to the effect that he has not read the markets correctly in recent years:

With a heavy heart, I will liquidate the funds and return capital—minus a small audit and tax holdback—by year’s end. My estimation of value in securities is not now, and has not been for some time, in sync with the markets.

To me, all this suggested that Burry’s traditional Graham-Dodd value-oriented approach had gotten run over by the raging tech bull market of the past eight years. I am sensitive to this, because I, too, have a gut bias towards value, which has not served me well in recent years. (A year ago I finally saw the light and publicly recanted value investing and embraced the bull, here on EWED).

Out of curiosity, therefore, I did some very shallow digging to try to find out how his Scion fund has performed in the last several years. I did not find the actual returns that investors would have seen. There are several sites that analyze the public filings of various hedge funds, and then calculate the returns on those stocks in those portfolio percentages. This is an imperfect process, since it will miss out on the actual buying and selling prices for the fund during the quarter, and may totally miss the effects of shorting and options and convertible warrants, etc., etc. But it suggests that Scion’s performance has not been amazing recently. Funds are nearly always shut down because of underperformance, not overperformance.

Pawing through sites like HedgeFollow (here and here) , Stockcircle, and Tipranks, my takeaway is that Burry probably beat the S&P 500 over the past three years, but roughly tied the NASDAQ (e.g. fund QQQ). This performance would naturally have his fund investors asking why they should be paying huge fees to someone who can’t beat QQQ.

What’s next for Burry? In a couple of tweets on X, Burry has teased that he will reveal some plans on November 25. The speculation is that he will refocus on some personal asset management fund, where he will not be bothered by whiny outside investors. We shall see.

Joy in French Magazine on Fast Fashion

The French magazine L’Express is widely read as magazines go. I was asked to give comments on fast fashion. An interview with me has been published in French at

Idées: Alors que Shein provoque une controverse nationale en France, l’économiste américaine invite à un regard nuancé sur la fast fashion, rappelant que le trop-plein de vêtements est un problème très récent dans l’histoire humaine.

Ideas: While Shein is causing a national controversy in France, the American economist urges a more nuanced view of fast fashion, reminding us that the overabundance of clothing is a very recent problem in human history.

I enjoyed talking with their reporter Thomas Mahler (kindly for me, in English). He informed me that French politicians are proposing to ban Shein from the country, meanwhile millions of people in France shop through Shein regularly.

Much overlap with my article: Fast Fashion, Global Trade, and Sustainable Abundance

Forget not that I also am featured in a French economics textbook for my drawing of a fat mouse. Vive la France!

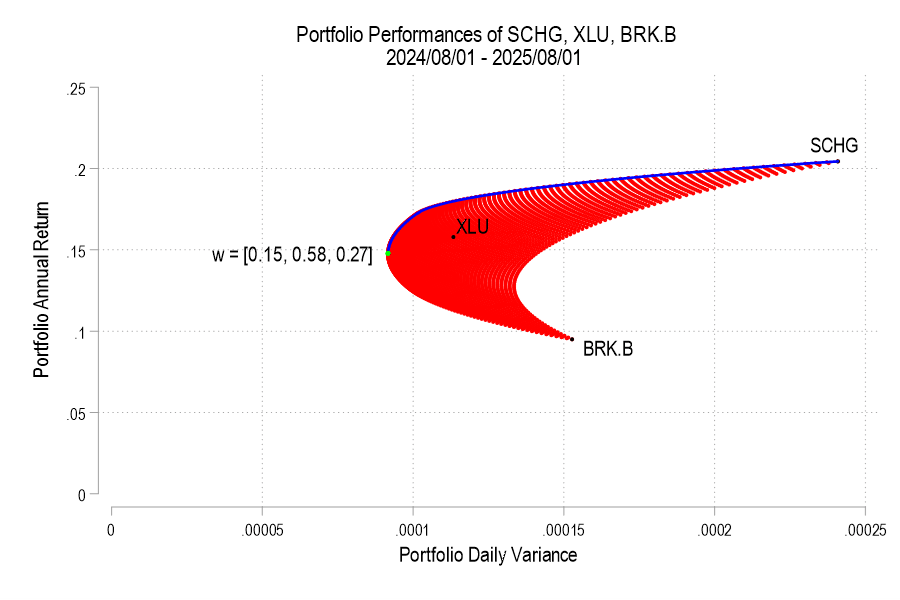

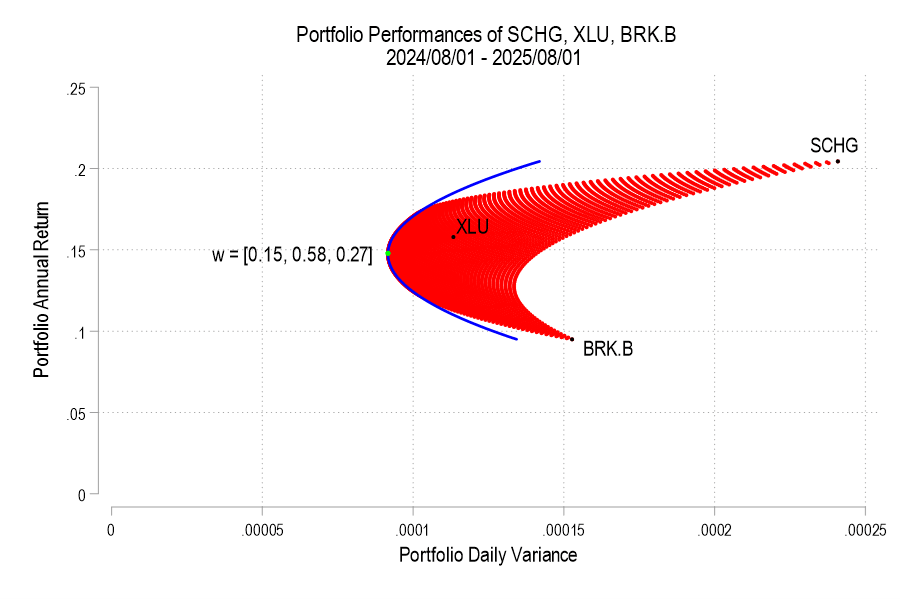

Portfolio Efficient Frontier Parabolics

Previously, I plotted the possible portfolio variances and returns that can result from different asset weights. I also plotted the efficient frontier, which is the set of possible portfolios that minimize the variance for each portfolio return.* In this post, I elaborate more on the efficient frontier (EF).

To begin, recall from the previous post the possible portfolio returns and variances.

From the above the definitions we can see that the portfolio return depends on the asset weights linearly and that the variance depends on the asset weights quadratically because the two w terms are multiplied. Since the portfolio return can be expressed as a function of the weights, this implies that the variance is also a quadratic function of returns. Therefore, every possible portfolio return-variance pair lies on a parabola. So, it follows that every pair along the efficient frontier also lies on a parabola. Not every pair lies on the same parabola, however – the efficient frontier can be composed on multiple parabolas!

I’ll use the same 3 possible assets from the previous post, below is the image denoting the possible pairs, the EF set, and the variance-minimizing point.

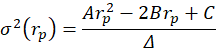

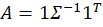

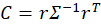

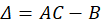

One way to find the EF is to calculate every possible portfolio variance-return pair and then note the greatest return at each variance. That’s a discrete iterative process and it definitely works. One drawback is that as the number of assets can increase the number of possible weight combinations to an intractable number that makes iterative calculations too time consuming. So, we can instead just calculate the frontier parabolas directly. Below is the equation for a frontier parabola and the corresponding graph.

Notice that the above efficient frontier doesn’t appear quite right. First, most obviously, the portion below the variance-minimizing return is inapplicable – I’ve left it to better illustrate the parabola. Near the variance-minimizing point, the frontier fits very nicely. But once the return increases beyond a certain level, the frontier departs from the set of possible portfolio pairs. What gives? The answer is that the parabola is unconstrained by the weights summing to zero. After all, a parabola exists at the entire domain, not just the ones that are feasible for a portfolio. The implication is that the blue curve that extends beyond the possible set includes negative weights for one or more of the assets. What to do?

As we deduced earlier, each pair corresponds to a parabola. So, we just need to find the other parabolas on the frontier. The parabola that we found above includes the covariance matrix of all three assets, even when their weights are negative. The remaining possible parabolas include the covariance matrices of each pair of assets, exhausting the non-singular asset portfolios. The result is a total of four parabolas, pictured below.