Last month Eric Basmajian published “Why Demographics Matter More Than Anything (For The Long Term)” on the financial site Seeking Alpha. He predicts that that the developed world plus China face a future of low economic growth (regardless of policy machinations) due simply to demographics. His key points:

Demographics are the most important factor for long-term analysis.

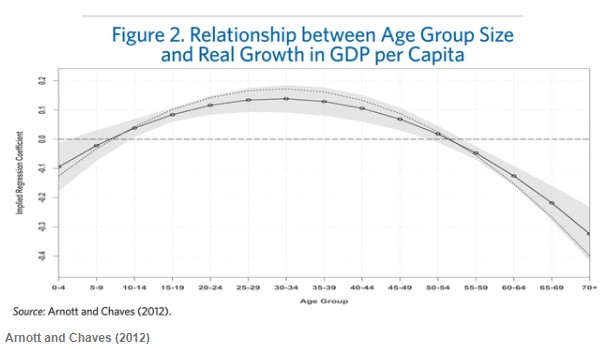

The young and old age cohorts negatively impact economic growth.

The prime-age population (25-64) drives the bulk of economic activity.

The world’s major economies are suffering from lower population growth and an older population.

Over the long run, the world’s major economies will have worse economic growth, which will negatively impact pro-cyclical asset prices (like stocks).

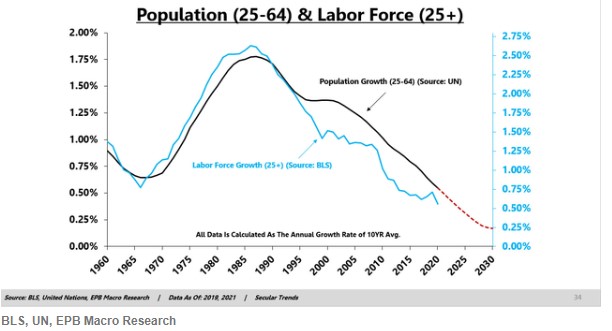

I will paste in some of his supporting charts. First, the labor force is more or less proportional to the 25-64 age cohort (U.S. data shown) :

…and GDP growth trends with labor force growth:

Also, on the consumption side, that is highest with the 25-54 age group:

And so,

Younger people are a drag on economic growth and older people are a drag on economic growth… The prime-age population is the segment that drives economic activity, so if the share of population that is 25-54 is shrinking, which it is, then you’re going to have more people that are a negative force than a positive force:

Once the working-age population growth flips negative, an economy is doomed…. Working age population growth in Japan flipped negative in the 1990s, and they moved to negative interest rates, QE, and they have never been able to stop. The economy is too weak.

After 2009, the working-age population in Europe flipped negative, and they moved to negative rates and QE, and they haven’t been able to stop. Even now, as the US is raising rates, Europe is struggling to catch up and has already abandoned most of its tightening plans.

In 2015, China’s working-age population flipped negative, and they’ve had problems ever since. They devalued their currency in 2015 and tried one more time to inflate a property bubble, but it didn’t work, and now they’re having to manage the deflation of an asset bubble that the population cannot support.

The US is in better shape than everyone else, but we’re not looking at robust growth levels in this prime-age population.

In conclusion, “ The real growth rate in most developed nations is collapsing because of those two factors, worsening demographics, and increased debt burdens. In the US, as a result of the demographic trends I just outlined plus a rising debt burden, real GDP per capita can barely sustain 1% increases over the long run compared to 2.5% in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.”

That is pretty much where Basmajian leaves it. No actionable advice (besides subscribing to his financial newsletter). What isn’t addressed is whether productivity (production per worker) can somehow be accelerated. Also, one of his charts (which I did not copy here) showed a big trend down in 25-64 age fraction in the US population in the 1950’s-1960’s (as hangover from the Depression?), and yet these were decades of strong GDP growth. So these demographic trends are not the whole story, but his analysis is sobering.