- Networking remains underrated, even though people talk about it. I think it’s underrated because when people do a good job with it they don’t notice that they are doing it. Whereas, you don’t, for example, teach a class and not notice that you did it.

- I’m reading Hillbilly Elegy in paperback. With the new edition in hand, what I noticed first was the pages of breathless reviews from every outlet you could ever want praise from (NYT, WSJ, Vox, Rolling Stone, etc.). How did he do it? Did “they” come to him? Did he go to them? What on earth happened? See above point #1. Halfway in, I agree with the blurb from The Atlantic that it is a “beautiful memoir.” Although I’m sorry not to be supporting independent bookstores more, my strategy these days is to buy used paperbacks through Amazon. The books themselves are nearly free and shipping still costs less than Kindle. (This is how AI can help us reduce trash – get the stuff we have already manufactured to the people who want it.)

- “Fewer students are benefiting from doing their homework: an eleven-year study” Via LinkedIn post by Ethan Mollick. Students might even learn less from homework if they use ChatGPT. Relatedly, SAT standards might be declining even if scores are not.

- Shruti Rajagopalan discusses talent in India

- “The rise of cultural Christianity” (The New Statesman) via Sam Enright

Uncategorized

More Immigrants, More Safety

The headlines often read with the criminal threats that illegal/undocumented immigrants pose to the US native population. The story usually includes a heart wrenching and tragic story about a native minor who was harmed by an immigrant and a politician to help propose a solution. There’s also usually a number cited for how many such crimes happened in the most recent year with data. Stories like this are designed to provoke feelings – not to provoke thinkings.

First, the tragic story is probably not representative. Even if it is, the citation of a raw count of crimes is not communicative in a helpful way. Sometimes politicians will say something like “one victim of a crime by an illegal immigrant is too many”. But that seems like a silly argument to make *if* immigrants reduce the probability of being a victim of a crime.

I argue that (1) immigrants who commit crimes at a lower probability than the native population cause the native population to be safer and, counterintuitively, (2) immigrants who commit crimes at a *higher* probability than the native population cause the native population to be safer.

Continue readingWhy was the Democratic Convention so patriotic?

Election season tends to spoil watching sports that have ad breaks, but one positive (for me at least) is that there is constant pedagogical fodder for my public choice & political economy class, particularly with regards to the median voter thereom. The biggest gripe with the MVT that people just insist on bringing up is the minor detail that it is obviously always wrong, which just misses the point entirely. Politics is neither fast nor slow. It’s more geological in that is slow to change until it isn’t. It can be painfully slow to watch coalitions 1. Coalesce 2. Cooperate 3. Fall apart 4. Return to 1. But politics is also opportunistic, which means responses to context can sometimes manifest relatively quickly. I would argue that nothing can provoke a more stark change in a political coalition than when their opposition abandons a position or brand that appeals to the median voter.

I tend to view Trumpology the same way I view Sovietology: it’s interesting to consume out of curiosity but we probably won’t have a deep understanding and know who was right until 20 years after the fact. Warren Nutter was right about the Soviet Union being an industrial ruse, but in his time he was mostly dismissed. My mental model of Trump and his team is that he’s a bad-faith business person who leverages transaction costs to the hilt and whose narcissism makes him effective at assembling imcompetent yes men. But, and I can’t emphasize this enough, we don’t really know what’s happening internally, there’s just too much noise in the information stream. What we can effectively observe, however, is the policy bundle and platform messaging on which he is compaigning.

That bundle is overwhelmingly negative. Beyond traditional scapegoating, the picture being painted of the current United States is bleak. Pessimistic, dystopian imagery appeals to plenty of people from the left and right extremes, but I struggle to think of a time in US history where the median American did not believe in America as both a good idea and a good place to live. A lot of people when discussing the MVT focus on the prediction that both parties will, in a vaccuum, arrive at identical platforms, an idea that seems false on it’s face. This is not unlike the prediction of physics that a feather and a bowling ball will fall at the same velocity in a vacuum – to demostrate that they don’t from the top of your apartment building is to both miss the point and place the people around you in intellectual (if not mortal) danger.

The most important insight in the MVT is the gravity of the median. Or, in the case of the current election, the speed with which one party will reclaim any branding opportunities around said median when the opposition abandons them. I have no doubt there are some veteran leaders within the RNC that are fuming over the long term costs of letting the Democratic party claim the mantle of the more patriotic and optimistic party. These are the kind of brands that are hard to take from the opposition- you pretty much have to wait for them, in a moment of foolishness or chaotic happenstance, to release their grip. Which I suspect the Republicans have.

I have no doubt the Democrats will find a way to do makes similar mistakes with this or other positions in the future. Politics is chaos and the median voter is far easier to find on an abstract two-dimensional curve than in reality. But that doesn’t mean we can pretend the median voter isn’t out there and that they don’t matter. It’s a simple model that may always be wrong, but it will never lead you astray.

Top EWED Posts of 2024

The following are notable posts from 2024, in descending order by the number of views this year.

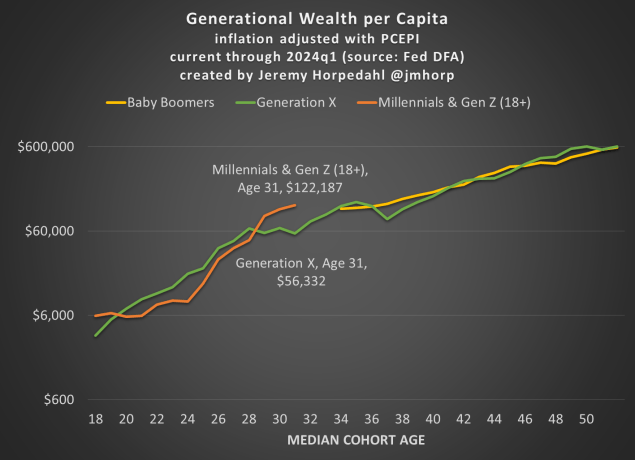

- Young People Have a Lot More Wealth Than We Thought Jeremy Horpedahl was first to this scene. American Millennials, on average, have money. Perhaps this is becoming common knowledge now among folks that read The Economist. The US is getting gradually richer, and the average young adult is benefiting. You can see more from Jeremy by following him on Twitter/X.

- Civil War as radical literalism Mike Makowsky writes, “There’s a million war movies, most of which have arcs and metaphors strewn throughout. The problem with making a moving about a hypothetical civil war in the modern United States is that the audience will spend so much time looking for the heroes, villains, and associated opportunities to feel morally superior that it seems almost impossible to deliver an effective portrayal of what it might actually feel like to wake up to a US civil war…”

- Is “Rich Dad Poor Dad” a Fraud? Scott explores whether a popular finance book is based on a false premise.

- Is the Universe Legible to Intelligence? I (Joy) do philosophy. It also has practical implications. Can machines outsmart us, for better or worse? How smart can anything physical be. Maybe, as @sama says, “intelligence is an emergent property of matter…” However, maybe “intelligence” only goes so far. We have many posts on artificial intelligence this year.

- How To Drive a Turbocharged Car, Such as a Honda CR-V This is one of those pieces by Scott that people find through search engines when they are looking for help.

- Grocery Price Nostalgia: 1980 Edition You can use our search function to find everything from this year about the topic of inflation.

- The US Housing Market Is Very Quickly Becoming Unaffordable

- Predicting College Closures James reflects on closing universities and what indicators might help stakeholders like parents and faculty anticipate the next event.

- Counting Jobs (Revisited) Jeremy did something that might have sounded boring at the time. Yet, soon afterwards there was serious interest in the question of : Did 818,000 jobs vanish?

- Why Avocado on Toast? As an avocado toast person, I loved this. I’m glad many other people found Zachary’s post interesting.

- Recovering My Frozen Assets at BlockFi, Part1. How Sam Bankman-Fried’s Fraud Cost Me.

- Why Don’t Full Daycares Raise Prices? The cost of childcare is an important issue. James wrote this from personal experience, and I pointed out something similar before.

- This post only got medium traffic in terms of the number of views this summer. Now that we know who the candidate will be, it’s interesting to look back and see a vindication of betting markets. Who Will Be the Democratic Presidential Candidate? Follow the Money (Betting Markets)

- Honorable mention to Mike’s post from 2022 that continues to get many search hits: Why Agent-Based Modeling Never Happened in Economics

At this point, the EWED authors have each written enough words to constitute a book. Watching this blog grow and flux with the rest of the internet has been fascinating.

You can subscribe to our WordPress site to get posts sent to your email. The widget for putting your email in should be on the right side of your screen on a computer, or you can find it by scrolling to the bottom of the home page on a mobile device. WordPress will let you customize your preferences so that you get emails batched once a week if you prefer that to Every Day.

Interpreting candidate policies

Interpreting policy talking points from people running for office is difficult for a variety reasons, but it essentially boils down to the fact that voters often do not want the outcomes that would be produced by the policies they will in fact vote for. Candidates, in turn, must find a way to promise policies they will either do their best not to deliver or, if they do deliver them, said policies will be bundled with other policies that will mitigate their effect.

Interpreting the true intended policy bundle being signaled by a candidate is fraught with traps, not least of which our personal biases. If I want to like a candidate, for social or identity reasons, I will have a tendency to interpret their policy proposals as part of a broader, unspoken, bundle that I like. If I don’t want to like a candidate, perhaps because they are a petty, boorish lout whose principle aptitude appears to be grifting at the margins of legality and leveraging the high transaction costs of our legal system, then I will subconsciously interpret each policy proposed as part of a more insidious unspoken bundle.

How should voters and pundits navigate an environment where information is limited and bias is largely unavoidable? I don’t know, but here’s how I try anyway.

- Assume every candidate has basic competency in appealing to their base.

- Assume every candidate wants to appeal to the median voter.

- Do not assume anyone knows who the median voter is.

- Assume both candidates and their advisors have the same capacity to assess how their respective bases will react to a proposal and how it will actually impact them, but do not assume they know how the median voter will react and be affected.

In essence, candidates will always have a deeper familiarity, with greater repeated interactions, with their voter and donor bases. They know how they will react and how they will actually be impacted. Platforms will be designed around navigating contexts where popularity and expected impact are in conflict. What this means is that, in the aggregate,

- A candidate stands to do the most damage when advocating for policies that will aid their base at the expense of the median

- A candidate will create the most uncertainty when the desires of their base are at odds with the consequences for their base.

For example, assume both major parties are advocating for trade restrictions. Let’s call them the Plurality party and the Majority parties. Trade restrictions will hurt the median voter, full stop. The Plurality party, whose indentity constitutes a minority of the total population but the largest share of the population of any subgroup, stands to gain the most through policies that extract from others in a negative sum game. It will be easier to take their candidate’s policies at face value because of uncertainty around the median voters preferences, in part due to voter uncertainty about how policies will affect them.

The Majority party, on the other hand, is more fractured in the subgroups that constitute its more numerous whole. They can be thought of an encompassing group coping with the high costs of intragroup bargaining. Their greater numerical advantage in elections is partly, if not wholly, nullified by difficulty solving collective action problems and their need to solve positive sum games whose benefits are spread too thinly to excite their base. Further, the Majority party is inclusive of the median voter, about which there is greater uncertainty. The Majority party, as such, has greater incentive to rely on a form of subtextual deception. To win elections, they will need to propose the policies that the various elements their base wants while also bundling them with other policy elements that will mitigate their consequences in the aggregate and leave options open downstream as consquences for the median are made manifest. Interpreting proposals of the Majority party demands more Straussian reading, which also means that greater care is needed in monitoring your own bias. Because all complex political economy aside, sometimes parties do in fact just have bad ideas.

Good luck.

Services, and Goods, and Software (Oh My!)

When I was in high school I remember talking about video game consumption. Yes, an Xbox was more than two hundred dollars, but one could enjoy the next hour of that video game play at a cost of almost zero. Video games lowered the marginal cost and increased the marginal utility of what is measured as leisure. Similarly, the 20th century was the time of mass production. Labor-saving devices and a deluge of goods pervaded. Remember servants? That’s a pre-20th century technology. Domestic work in another person’s house was very popular in the 1800s. Less so as the 20th century progressed. Now we devices that save on both labor and physical resources. Software helps us surpass the historical limits of moving physical objects in the real world.

There’s something that I think about a lot and I’ve been thinking about it for 20 years. It’s simple and not comprehensive, but I still think that it makes sense.

- Labor is highly regulated and costly.

- Physical capital is less regulated than labor.

- Software and writing more generally is less regulated than physical capital.

I think that just about anyone would agree with the above. Labor is regulated by health and safety standards, “human resource” concerns, legal compliance and preemption, environmental impact, and transportation infrastructure, etc. It’s expensive to employ someone, and it’s especially expensive to have them employ their physical labor.

Insuring the suspension of disapproval

My wife and I were watching Guy Ritchie’s “Sherlock Holmes” (2009) last night. There is a chase/fight scene where a large commercial ship being repaired along a dock is detroyed as collateral damage. She asked me “What are the consequences of that ship being destroyed?” I had to admit that I didn’t fully know the state of the insurance market in Victorian England, but suffice it to say a few businesses and/or families were likely ruined. Which led to a conversation about collateral damage outside of the main narrative in movies and insurance. Sorry, that’s just what happens when you marry an economist. Things to consider the next time you’re filtering your prospects.

Which got me thinking: how much does the suspension of our disapproval of the protagonist’s actions (similar to the suspension of disbelief) depend on our undeclared faith in the insurance market of a fictional world? We don’t worry about destroyed livelihoods because we assume everything is simply absorbed as a tail event against which everything is insured. Car through front window? Automotive insurance tail event. Plane crashing onto the Vegas strip? Aeronautical tail event. Godzilla’s tail sweeping through a city? Giant lizard tail tail event.

How about the rise of the antihero? How many heists include a character shouting exposition to a crowd of cowering bank customers that they are there to steal money from the insurance company rather than the customers? The filmmaker needs the audience to suspend disbelief that bank’s have multiple customers inside in the age smart phones and suspend disapproval of the morality of the thieves’ actions as they steal from what they can only hope the audience will deem a souless corporation that can absorb the loss without broader consequence.

There’s two intellectual rabbit holes you can go down when you start thinking about insurance. You can dive in vertically, asking how much of our daily lives, including the consumption of narratives, is dependent on the presumption of insurance. You can also start thinking horizontally: how many dimensions of our lives boil down to creating formal and informal sources of insurance. We acquire formal health, home, pet, and automotive insurance. We also join groups, like churches, synagogues, mosques, and (yes) cults for social insurance. One motive to have children is to insure against the limitations and isolation of old age. Anything and everything we invest in, both individually and as a society, that softens the tail events at the expense of the expected outcome is a form of insurance.

It can go on and on. If anything, it takes care at some point to stop seeing everything as a form of insurance. Why did they feature an actor in the poster and the trailer despite their only appearing for 14 minutes in the film? Why were they paid more than double the lead actors? Oh, right. They’re an insurance policy against a catastrophic opening weekend. If the movie is good, but needs word of mouth to spread for people to starting coming out, you need to survive to a second weekend to start making money. Better to eat a chunk of your expected profits on a big name than risk getting dumped from theaters before the audience can find you.

What’s that you say? No one goes to theater’s anymore? Oh. Well, there’s some risk you can’t insure against.

The median voter remains (probabilistically) undefeated

The median voter wanted a younger candidate. The median voter appears to now have a younger candidate. The immediate result:

Polymarket doesn’t have it crossing over yet, but Biden at his nadir before dropping out was at 34%. Today shares of Harris winning are at 45%. Put in equity terms, a share of the Democrative candidate winning has increased 33% in a month on Polymarket.

Biden got the nomination and eventually won in 2020 by appealing to the median voter, even while pundits from his base whined. Harris will, if she wants to win, do much of the same. It will be interesting to see if the Republican candidate responds in kind, but its difficult to the see the dimensions on which they can depart from their candidate’s highly, ahem…specific brand.

Tech Stocks Sag as Analysists Question How Much Money Firms Will Actually Make from AI

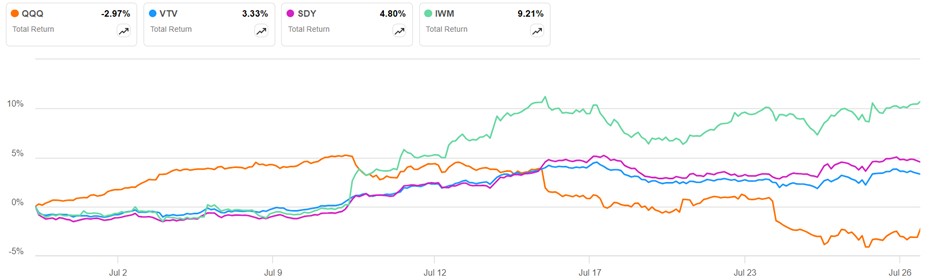

Tech stocks have been unstoppable for the past fifteen or so years. Here is a chart from Seeking Alpha for total return of the tech-heavy QQQ fund (orange line) over the past five years, compared to a value-oriented stock fund (VTV), a fund focused on dividend-paying stocks (SDY) and the Russel 2000 small cap fund IWM.

QQQ has left the others in the dust. There has been a reversal, however, in the past month. The tech stocks have sagged nearly 10% since July 11, while the left-for-dead small caps (IWM, green line) rose by 10%:

Some of this is just mean reversion, but there seems to be a deeper narrative shift going on. For the past 18 months, practically anything that could remotely be connected with AI, especially the Large Language Models (LLM) exemplified by ChatGPT, has been valued as though it would necessarily make every-growing gobs of money, for years to come.

In recent weeks, however, Wall Street analysts have started to question whether all that AI spending will pay off as expected. Here are some headlines and excerpts (some of the linked articles are behind paywalls):

““There are growing concerns that the return on investment from heavy AI spending is further out or not as lucrative as believed, and that is rippling through the whole semiconductor chain and all AI-related stocks,” said James Abate, chief investment officer at Centre Asset Management.”

““The overarching concern is, where is the ROI on all the AI infrastructure spending?” said Alec Young, chief investment strategist at Mapsignals. “There’s a pretty insane amount of money being spent.

Jim Covello, the head of equity research at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., is among a growing number of market professionals who are arguing that the commercial hopes for AI are overblown and questioning the vast expense required to build out infrastructure required for the computing to run and train large-language models.”

“It really feels like we are moving from a ‘tell me’ story on AI to a ‘show me’ story,” said Ohsung Kwon, equity and quantitative strategist at Bank of America Corp. “We are basically at a point where we’re not seeing much evidence of AI monetization yet.”

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/earnings-derail-stock-rally-over-130001940.html

Goldman’s Top Stock Analyst Is Waiting for AI Bubble to Burst

Covello casts doubt on hype behind an $16 trillion rally

He says costs, limited uses means it won’t revolutionize world

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/goldman-top-stock-analyst-waiting-111500948.html

Google stock got dinged last week for excessive capital spending, even though earnings were strong. Microsoft reports its Q4 earnings after the market closes today (Tuesday); we will see how investors parse these results.

On field experiments and null effects

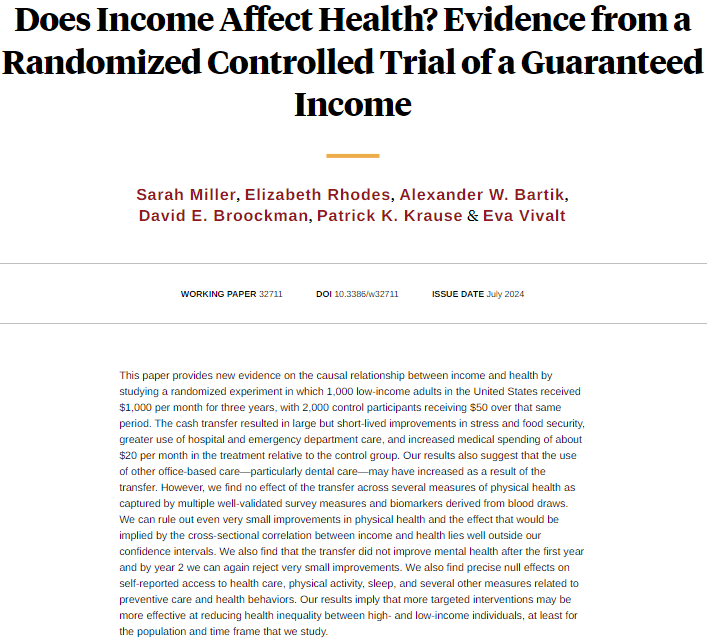

The most interesting new paper in months dropped in last week: “Does Income Affect Health? Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial of a Guaranteed Income“

All the broad strokes are there in the abstract: $1000 per month, 2,000 participants (half treated), for three years. It’s the biggest, highest salience experimental test of a universal basic income program to date. There’s a lot of detail, but the broad strokes findings are that nothing happened. That is to say, there was a lot of precise null effects. And that is absolutely fascinating! I’ve gone back in forth on my feelings about a large scale UBI policy, and this is certainly more evidence that gives me pause, but my biggest takeaway is that policy research really should culimate in a series of field experiments whenever possible. Not because of identification or external validity or any of the other reasons economists fight in intellectual perpetuity, but because it’s easier to accept null results as sufficiently precise. It’s easier to acknowledge and accept that there is no observed effect because the treatment mechanism truly had no net effect within an experimental design.

Conducting research using observational data to produce causally identified conclusions is to fight a battle on multiple fronts. These fronts usually relate to the all the possible sources of bias, of endogeneity, within your analysis. You’re observing x causing y to increase, but the reality is that x is correlated with z, and that is what is actually causing y to increase. That’s a tough fight, believe me, as hypothetical sources of varying degrees of plausibility are hurled at your analysis from all directions. But at least there is an argument to be had. There’s something to fight against and over.

Null results face a far more insidious argument: there’s just too much noise in your analysis. Too many sources of variation, to much measurement error, too much something (that I don’t have to bother unpacking) and that’s why your standard errors are too big to identify the true underlying effect. There’s also a simple, and annoying, institutional reality: there’s no t-test for a precise zero. There’s no p value, so threshold for statistical significance that says this is a “true zero”. All we can say is that the results fail to reject the null. It’s subjective. And in a world of 2 percent acceptance rates at top journals, good luck getting through a review process where the validity of statistical interpretaton is assessed in a purely subjective manner.

Field experiments enjoy far more grace with null results. As random control trials, they can argue that their null effects are, in fact, causally estimated. If conducted within sufficient power (i.e. number of observations relative to feasible impact), then the results are simply the results. There’s no arguments to be had about instrumental variables, regression discontinuity cutoffs, or synthetic control designs. Measurement error will rarely be a problem given an appropriate design. External validity…well there’s no getting around external validity gripes, but should those concerns appear then the opposition has already accepted the statistical validity of your null results. You’ve already won.

I’m not puffing up my own team here, either. I’ve conducted several lab experiments, but never a field experiment. They are large, lengthy, and costly endeavors. I aspire to run a couple before my career runs its course, but I’ve built nothing on them to date. But they’ve grown in my estimation, even admidst concerns over participant gaming and external validity, precisely because you can run your experiment, observe no measurable impact on anything, and proclaim in earnest that that is precisely what happened. Nothing.