A big narrative for the past fifteen years has been that “software is eating the world.” This described a transformative shift where digital software companies disrupted traditional industries, such as retail, transportation, entertainment and finance, by leveraging cloud computing, mobile technology, and scalable platforms. This prophecy has largely come true, with companies like Amazon, Netflix, Uber, and Airbnb redefining entire sectors. Who takes a taxi anymore?

However, the narrative is now evolving. As generative AI advances, a new phase is emerging: “AI is eating software.” Analysts predict that AI will replace traditional software applications by enabling natural language interfaces and autonomous agents that perform complex tasks without needing specialized tools. This shift threatens the $200 billion SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) industry, as AI reduces the need for dedicated software platforms and automates workflows previously reliant on human input.

A recent jolt here has been the January 30 release by Anthropic of plug-in modules for Claude, which allow a relatively untrained user to enter plain English commands (“vibe coding”) that direct Claude to perform role-specific tasks like contract review, financial modeling, CRM integration, and campaign drafting. (CRM integration is the process of connecting a Customer Relationship Management system with other business applications, such as marketing automation, ERP, e-commerce, accounting, and customer service platforms.)

That means Claude is doing some serious heavy lifting here. Currently, companies pay big bucks yearly to “enterprise software” firms like SAP and ServiceNow (NOW) and Salesforce to come in and integrate all their corporate data storage and flows. This must-have service is viewed as really hard to do, requiring highly trained specialists and proprietary software tools. Hence, high profit margins for these enterprise software firms.

Until recently, these firms been darlings of the stock market. For instance, as of June, 2025, NOW was up nearly 2000% over the past ten years. Imagine putting $20,000 into NOW in 2015, and seeing it mushroom to nearly $400,000. (AI tells me that $400,000 would currently buy you a “used yacht in the 40 to 50-foot range.”)

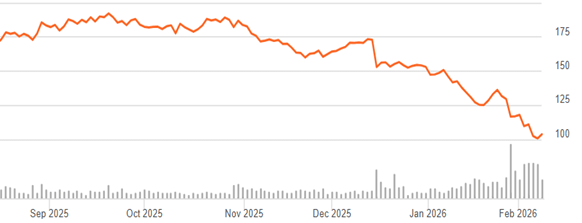

With the threat of AI, and probably with some general profit-taking in the overheated tech sector, the share price of these firms has plummeted. Here is a six-month chart for NOW:

Source: Seeking Alpha

NOW is down around 40% in the past six months. Most analysts seem positive, however, that this is a market overreaction. A key value-add of an enterprise software firm is the custody of the data itself, in various secure and tailored databases, and that seems to be something that an external AI program cannot replace, at least for now. The capability to pull data out and crunch it (which AI is offering) it is kind of icing on the cake.

Firms like NOW are adjusting to the new narrative, by offering pay-per-usage, as an alternative to pay-per-user (“seats”). But this does not seem to be hurting their revenues. These firms claim that they can harness the power of AI (either generic AI or their own software) to do pretty much everything that AI claims for itself. Earnings of these firms do not seem to be slowing down.

With the recent stock price crash, the P/E for NOW is around 24, with a projected earnings growth rate of around 25% per year. Compared to, say, Walmart with a P/E of 45 and a projected growth rate of around 10%, NOW looks pretty cheap to me at the moment.

(Disclosure: I just bought some NOW. Time will tell if that was wise.)

Usual disclaimer: Nothing here should be considered advice to buy or sell any security.