One of the oldest theories in economics is the idea of compensating differentials. A job represents not just a certain amount of money per hour, but a whole package of positive and negative things. Jobs have more or less stability, flexibility, fun, room to grow, danger… and non-cash benefits like health insurance. The idea of compensating differentials is that, all else equal, jobs that are good on these other margins can pay lower cash wages and still attract workers (thus, the danger of doing what you love). On the other hand, jobs that are bad on these other margins need high wages if they want to hire anyone (thus, the deadliest catch)

I think this theory makes perfect sense, and we see evidence for it in many places. But when it comes to health insurance, everything looks backwards. A job that offers employer-provided health insurance is better to most employees than one that doesn’t, so by compensating differentials it should be able to offer lower wages. There’s just one problem: US data shows that jobs offering health insurance also offer significantly higher wages. The 2018 Current Population Survey shows that workers with employer-provided health insurance had average wages of $33/hr, compared to $24/hr for those without employer insurance.

All the economists are thinking now: that’s not a problem, compensating differentials is an “all else equal” claim, but not all else is equal here. The jobs with health insurance pay higher wages because they are trying to attract higher-skilled workers than the jobs that don’t offer insurance.

That’s what I thought too. It is true that jobs with insurance hire quite different workers on average:

The problem is, once we control for all the observable ways that insured workers differ, we still find that their wages are significantly higher than workers who don’t get employer-provided insurance. Like, 10-20% higher. That’s after controlling for: year, sex, education, age, race, marital status, state of residence, health, union membership, firm size, whether the firm offers a pension, whether the employee is paid hourly, and usual hours worked. I’ve thrown in every possibly-relevant control variable I can think of and employer-provided health insurance always still predicts significantly higher wages. Of course, there are limits to what we get to observe about people using surveys; I don’t get any direct measures of worker productivity. Possibly the workers who get insurance are more skilled in ways I don’t observe.

We can try to account for these unobserved differences by following the same person from one job to another. When someone switches jobs, they could have health insurance in both jobs, neither, only the new, or only the old. What happens to the wages of people in each of these situations? It turns out that gaining health insurance in a new job on average brings the biggest increase in wages:

What could be going on here? One possibility is that health insurance makes people healthier, which improves their productivity, which improves their wages. But we control for health status and still find this effect. The real mystery is that papers that study mandatory expansions of health insurance (like the ACA employer mandate and prior state-level mandates) tend to find that they lower wages. Why would employer-provided health insurance lower wages when it is broadly mandated, but raise wages for individuals who choose to switch to a job that offers it?

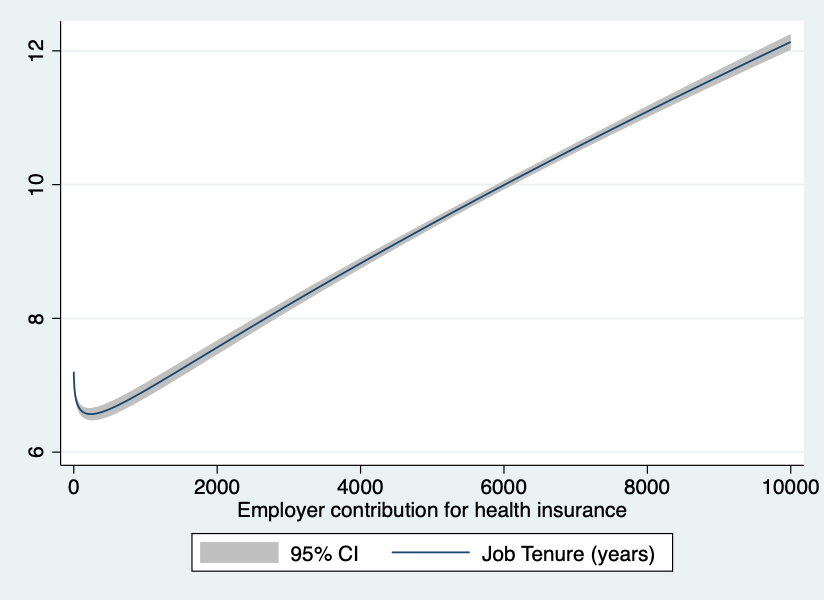

My current theory is that “efficiency benefits” are offered alongside “efficiency wages”. The idea of efficiency wages is that some firms pay above-market wages as a way of reducing turnover. Workers won’t want to leave if they know their current job pays above-market, and so the company saves money on hiring and training. But this only works if other firms aren’t doing it. The positive correlation of wages and insurance could be because the same firms that pay “efficiency wages” are more likely to pay “efficiency benefits”- offering unusually good benefits as a way to hold on to employees.

I still feel like these results are puzzling and that I haven’t fully solved the puzzle. This post summarizes a currently-unpublished paper that Anna Chorniy and I have been working on for a long time and that I’ll be presenting at WVU tomorrow. We welcome comments that could help solve this puzzle either on the empirical side (“just control for X”) or the theoretical side (“compensating differentials are being overwhelmed here by X”).