Yesterday the Biden administration announced that is forgiving up to $20k per person in student debt. So far we’ve seen lots of debate over whether this was a good/fair idea; as an economist who paid back his own debt early, you can probably guess what I have to say about that, so I’ll move on to the more interesting question of what happens now.

The above is a quote from Thomas Sowell as a political commentator, but he was also a great economist. His book Applied Economics says that the essence of the economic approach to policy analysis is to not just consider the immediate effect, but instead to keep asking “and then what?” So let’s try that here.

We’ll start with the immediate effects. Those whose debt just fell will be happy, and will have more money to spend or save in other ways. The federal government is on the other side of this, they’ll receive less in debt payments and so will have to fund themselves in other ways like borrowing money or raising taxes. People are still trying to estimate how big this transfer from the government to student debtors is, but let’s take the Penn Wharton Budget Model estimate of $330 billion (the actual cost is likely higher, since that estimate is for $10k of loan forgiveness, but the actual program forgives up to $20k for those who had Pell grants). Dividing by US population tells you the cost is roughly $1000 per American; dividing by $10,000 tells you that roughly 33 million debtors benefit.

OK, what happens next? The big question is: is this a one-time thing, or does it make future loan forgiveness more or less likely? Later I’ll make the argument for why the answer could be “less”. But right now most people seem to think the answer is “more”, and that belief is what will be driving decisions.

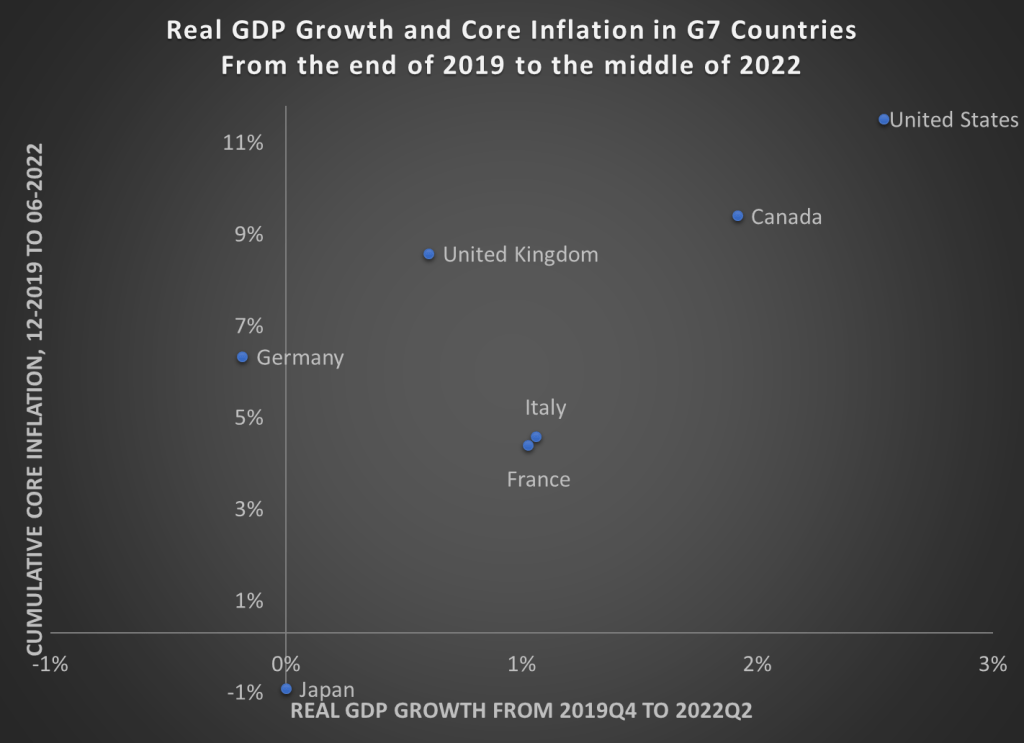

If current and future students think loan forgiveness is likely, they have an incentive to take out more loans than they otherwise would, and to pay them off more slowly (particularly since income-based repayment was just cut from 10% to 5% of income). This higher willingness to pay from students gives colleges an incentive to raise tuition; historically about 60% of subsidized loans to students end up captured by colleges in the form of higher prices:

We find a pass-through effect on tuition of changes in subsidized loan maximums of about 60 cents on the dollar, and smaller but positive effects for unsubsidized federal loans. The subsidized loan effect is most pronounced for more expensive degrees, those offered by private institutions, and for two-year or vocational programs.

Source: https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr733.html

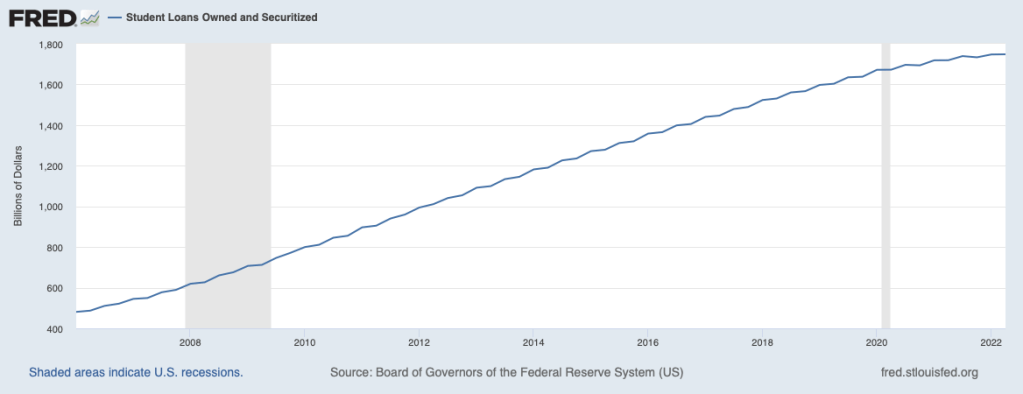

To the extent that you think student debt is a national problem, this action didn’t solve the problem so much as push it back 6 years; wiping out roughly 20% of all student debt brings us back to 2016 levels. So we could end up right back here in 2028, possibly faster to the extent that students borrow more as a result.

That, together with the “normalization” of student loan forgiveness, is why people think a similar action in the future is likely. But I’ll give two reasons it might not happen.

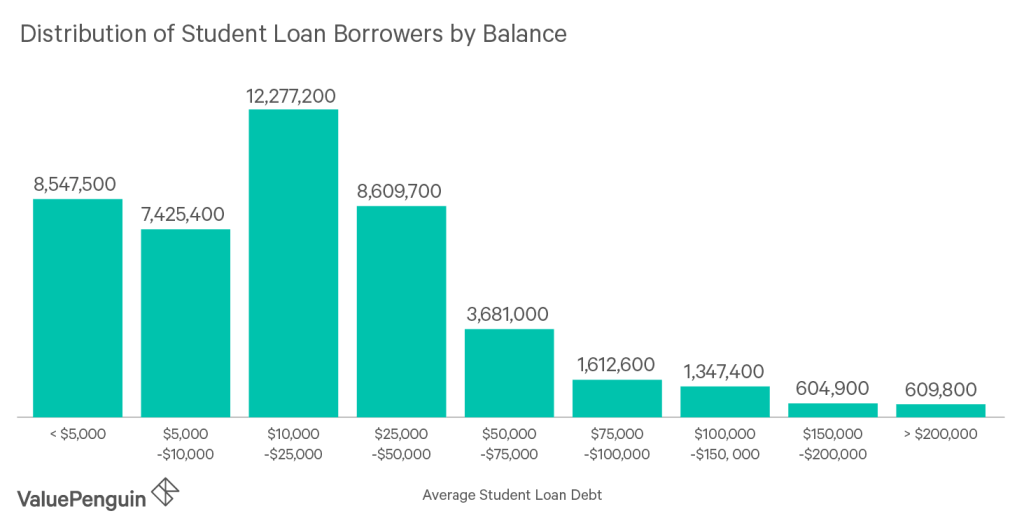

First, this action may have only reduced student debt by about 20%, but it reduced the number of student debtors much more (at least 36%), because most debtors owed relatively small amounts. It will take more than 6 years for the number of voters who’d benefit from loan forgiveness to get back to what it was in 2022, reducing support for forgiveness in the mean time.

That also gives Congress plenty of time to do something, even by their lethargic standards. Part of what bothers many people about this loan forgiveness is that it not only doesn’t solve the underlying issue of the Department of Education signing kids up for decades of debt, it will likely worsen the underlying issue through the moral hazard effect I describe above. Forgiveness would be much more popular if it were paired with reforms to solve the underlying issue. While we aren’t getting real reform now, I do think forgiveness makes it more likely that we’ll see reform in the next few years. What could that look like?

Let’s start with the libertarian solution, which of course won’t happen:

More realistic will be limits on where Federal loan money can be spent, and shared responsibility for colleges. Colleges and the government have spent decades pushing 18 year olds to sign up for huge amounts of debt. While I’d certainly like to see 18-year-olds act more responsibly and “just say no” to the pushers, the institutions bear most of the blame here. The Department of Education should raise its standards and stop offering loans to programs with high default rates or bad student outcomes. This should include not just fly-by-night colleges, but sketchy masters degree programs at prestigious schools.

Colleges should also share responsibility when they consistently saddle students with debt but don’t actually improve students’ prospects enough to be able to pay it back. Economists have put a lot of thought into how to do this in a manner that doesn’t penalize colleges simply for trying to teach less-prepared students.

I’d bet that some reform along these lines happens in the 2020’s, just like the bank bailouts of 2008 led to the Dodd-Frank reform of 2010 to try to prevent future bailouts. The big question is, will this be a pragmatic bipartisan reform to curb the worst offenders, or a Republican effort to substantially reduce the amount of money flowing to a higher ed sector they increasingly dislike?