The drama continues for Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF), the former head of now-bankrupt crypto exchange FTX. This past week has been giving a series of interviews, in which he (the brilliant master, the White Knight, of the crypto world a mere month ago) is trying to convince us (potential jurors?) that he is too dim-witted to have masterminded a shell game of international wire transfers, and that he had no idea what was happening in the closely-held company of which he was Chief Executive Officer. (For an entertaining take on what We The People think of SBF’s disclaimers, see responses in this thread ttps://twitter.com/SBF_FTX/status/1591989554881658880, especially the video posted by “Not Jim Cramer”).

The word on the street is that his former partner Caroline Ellison (who he has been implicitly throwing under the bus with his disclaimers of responsibility for the multi-billion dollar transfers from his FTX to her Alameda company) may well be cutting a deal with prosecutors to testify against SBF. It remains to be seen whether SBF’s monumental political donations will suffice to keep him from doing hard time.

But all that legal drama aside, the SBF saga brings up some interesting issues on risk management. Earlier here on EWED James Bailey highlighted a revealing exchange between SBF and Tyler Cowen, in which SBF displayed a heedless neglect of the risk of catastrophic outcomes, as long as there is a reasonable chance of great gain:

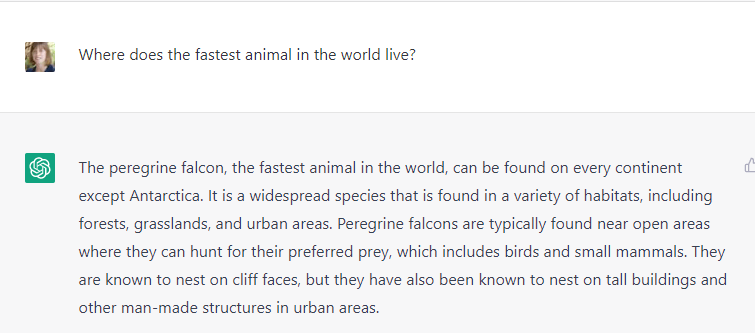

TC: Ok, but let’s say there’s a game: 51% you double the Earth out somewhere else, 49% it all disappears. And would you keep on playing that game, double or nothing?

SBF: Yeah…take the pure hypothetical… yeah.

TC: So then you keep on playing the game. What’s the chance we’re left with anything? Don’t I just St. Petersburg Paradox you into non-existence?

SBF: No, not necessarily – maybe [we’re] St. Petersburg-paradoxed into an enormously valuable existence. That’s the other option.

Boiled down, the St Petersburg Paradox involves a scenario where you have a 50% chance of winning $2.00, a 25% (1/4) chance of winning $4.00, a 1/8 chance of winning $8.00, and so on without limit. If you add up all the probabilities multiplied by the amount won for each probability, the Expected Value for this scenario is infinite. Therefore it seems like it would be rational, if you were offered a chance to play this game, to stake 100% of your net worth in one shot. However, almost nobody would actually do that; most folks might spend something like $20 or maybe 0.1% of their net worth for a shot at this, since the likely prospect of losing a large amount does not psychologically compensate for the smaller chance of gaining a much, much larger amount. But SBF is not “most folks”.

Victor Haghani recently authored an article on risk management and on SBF’s approach:

Most people derive less and less incremental satisfaction from progressive increases in wealth – or, as economists like to say: most people exhibit diminishing marginal utility of wealth. This naturally leads to risk aversion because a loss hurts more than the equivalent gain feels good. The classic Theory of Choice Under Uncertainty recommends making decisions that maximize Expected Utility, which is the probability-weighted average of all possible utility outcomes.

SBF explained on multiple occasions that his level of risk-aversion was so low that he didn’t need to think about maximizing Expected Utility, but could instead just make his decisions based on maximizing the Expected Value of his wealth directly. So what does this mean in practice? Let’s say you find an investment which has a 1% chance of a 10,000x payoff, but a 99% chance of winding up worth zero. It has a very high expected return, but it’s also very risky. How much of your total wealth would you want to invest in it?

There’s no right or wrong answer; it’s down to your own personal preferences. However, we think most affluent people would invest somewhere between 0.1% and 1% of their wealth in this investment, based on observing other risky choices such people make and surveys we’ve conducted…

SBF on the other hand, making his decision strictly according to his stated preferences, would choose to invest 100% of his wealth in this investment, because it maximizes the Expected Value of his wealth.

Even in a game with a fair 50/50 outcome, a player with finite resources will eventually go broke. This is the “Gambler’s Ruin” concept in statistics. SBF’s outsized penchant for risk took his net worth to something like $30 billion earlier this year, something we more-timid souls will never achieve, but it eventually proved to be his undoing.

Most people have a more or less logarithmic sense of the utility of money – if you only have $1000, the gain or loss of $100 is significant, whereas $100 is lost in the noise for someone whose net worth is over a million dollars. SBF apparently felt that he was playing with such big numbers, that he did not need to worry about big losses, as long as there was a chance at a big, big win. Here is a Twitter Thread by SBF, from Dec 10, 2020:

SBF: …What about a wackier bet? How about you only win 10% of the time, but if you do you get paid out 10,000x your bet size?

[So, if you have $100k,] Kelly* suggests you only bet $10k: you’ll almost certainly lose. And if you kept doing this much more than $10k at a time, you’d probably blow out.

…this bet is great Expected Value; you win [more precisely, your Expected Value is] 1,000x your bet size.

…In many cases I think $10k is a reasonable bet. But I, personally, would do more. I’d probably do more like $50k.

Why? Because ultimately my utility function isn’t really logarithmic. It’s closer to linear.

…Kelly tells you that when the backdrop is trillions of dollars, there’s essentially no risk aversion on the scale of thousands or millions.

Put another way: if you’re maximizing EV(log(W+$1,000,000,000,000)) and W is much less than a trillion, this is very similar to just maximizing EV(W).

Does this mean you should be willing to accept a significant chance of failing to do much good sometimes?

Yes, it does. And that’s ok. If it was the right play in EV, sometimes you win and sometimes you lose.

(*The Kelly criterion is a formula that determines the optimal theoretical size for a bet.)

Haghani concludes, “It seems like SBF was essentially telling anyone who was listening that he’d either wind up with all the money in the world, which he’d then redistribute according to his Effective Altruist principles – or, much more likely, he’d die trying.”

( Full disclosure: I have lost an irritating amount of money thanks to SBF’s shenanigans. My BlockFi crypto account is frozen due to fallout from the FTX collapse, with no word on if/when I might see my funds again. )