Universities have been around for about a thousand years, but for much of that time it was typical for cutting-edge research to happen outside of them. Copernicus wasn’t a professor, Darwin wasn’t a professor. Others like Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke, and Albert Einstein became professors only after completing some of their best work. Scientists didn’t need the resources of a university, they simply needed a means of support that gave them enough time to think. Many were independently wealthy (Robert Boyle, Antoine Lavoisier) or supported by the church (Gregor Mendel). Some worked “real jobs”, David Ricardo as a banker, Einstein famously as a patent clerk.

Over time academia grew and an increasing share of research was done by professors, with most of the rest happening inside the few non-academic institutions that paid people to do full time research: national labs, government agencies, and a few companies like Xerox Parc, Bell Labs and 3M. In many fields research came to require expensive equipment that was only available in the best-funded labs. “Researcher” became a job, and research conducted by those without that job became viewed with suspicion over the 20th century.

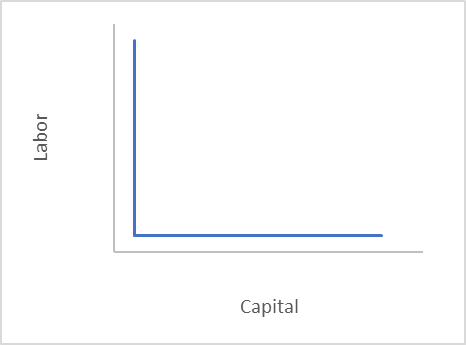

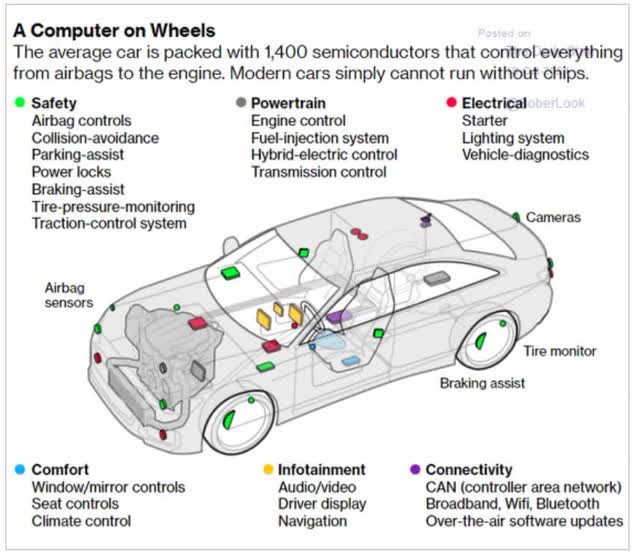

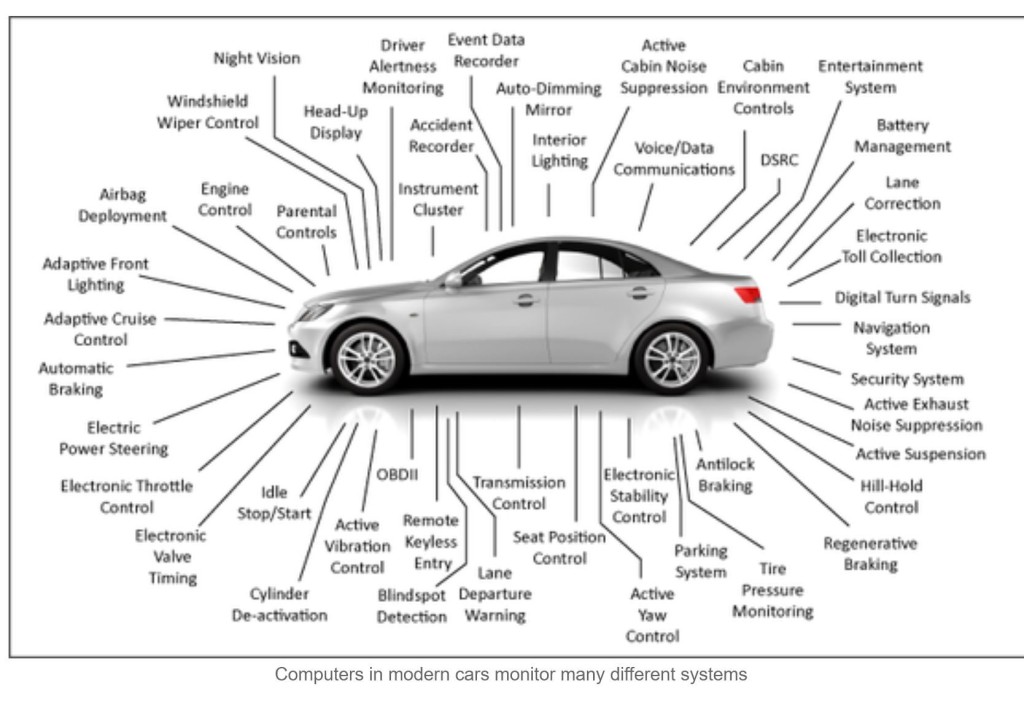

But the Internet Age is leading to the growth in opportunities outside academia, opportunities not just economic but intellectual. Anyone with a laptop and internet can access most of the key tools that professors use, often for free- scientific articles, seminars, supercomputers, data, data analysis. Particularly outside of the lab sciences, the only remaining barrier to independent research is again what it was before the 20th century- finding a means of support that gives you time to think. This will never be easy, but becoming a professor isn’t either, and a growing number of people are either becoming independently wealthy, able to support themselves with fewer work hours (even vs academics), or finding jobs that encourage part time research. If you work for the right company you might even get better data than the academics have.

Particularly in artificial intelligence and machine learning, the frontier seems to be outside academia, with many of the best professors getting offers from industry they can’t refuse.

Even in the lab sciences, money is increasingly pouring in for those who want to leave academia to run a start-up instead:

I think it’s great for science that these new opportunities are opening up. A natural advantage of independent research is that it allows people to work on topics or use methods they couldn’t in academia because they are seen as too high risk, too out there, make too many enemies, or otherwise fall into an academic “blind spot“.

I’m still happy to be in academia, and independent research clearly has its challenges too. But over my lifetime it seems like we have shifted from academia being the obvious best place to do research, to academia being one of several good options. Even as research has begun to move elsewhere though, universities still seem to be doing well at their original purpose of teaching students. Almost all of the people I’ve highlighted as great independent researchers were still trained at universities; most of the modern ones I linked to even have PhDs. There are always exceptions and the internet could still change this, but for now universities retain a near-monopoly on training good researchers even as the employment of good researchers becomes competitive.

As an academic I may not be the right person to write about all this, so I’ll leave you with the suggestion to listen to this podcast where Spencer Greenberg and Andy Matuschak discuss their world of “para-academic research”. Spencer is a great example of everything I’ve said- an Applied Math PhD who makes money in private sector finance/tech but has the time to publish great research, partly in math/CS where a university lab is unnecessary, but more interestingly in psychology where being a professor would actually slow him down- independent researchers don’t need to wait weeks for permission from an institutional review board every time they want to run a survey.