Joy got tenure! Texas took away tenure? North Carolina is trying to take away tenure. It’s become, at least to some, an open question as to why we grant faculty lifetime contracts after a certain benchmark of their career. So I’m going to answer it.

But first a point of clarification. I think we sometimes confuse benefits with reasons. Intellectual freedom is a benefit of tenure, a byproduct possibly, but I don’t think that is a reason. There is no shortage of industries and fields that would benefit from creative, intellectual, and artistic freedom, but we don’t tenure them. Just ask any of the major film directors of the last 50 years how much job security they’ve enjoyed and they’ll laugh out loud. I think it is pretty safe to say we’d probably observe greater artistic integrity in a variety of fields if people could fall back on a lifetime contract, albeit integrity coupled with some dropoff in productivity. Tenure remains a rare commodity across labor contracts.

So why tenure in academia?

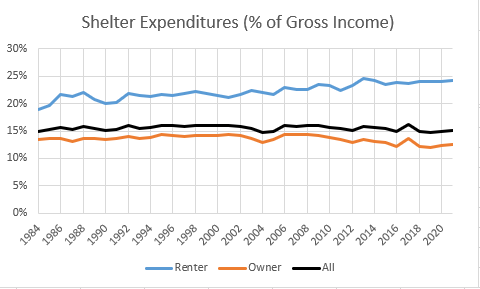

To become an academic researcher is to make an enormous upfront investment in human capital, often remaining in school until someone’s late 20s, even early 30s. These are people who often have a relatively high opportunity cost of time, even early in their careers, and they do this while also staring down the possibility of technical obsolescence within a decade of graduation. An academic, if they make a major contribution, often knows it will happen before they turn 40 (30 if they’re a mathematician). This is not a trivial endeavor or decision.

Building a critical mass of high quality employees when such high opportunity costs underlie the requisite labor pool presents a financial challenge. In the face of these costs, as much as half of academic compensation takes the form of non-pencuniary benefits (lifestyle, freedom, flexibility, status, etc). And there’s one more problem, and it might be the biggest. For those in more technical fields, the full career’s worth of (discounted) wages would have to be collected in their first 8 years on the job. To put it another way, for the academic labor market to clear absent these non-pecuniary benefits, salaries would have to double or more.

There should be little doubt in your mind that all but a tiny fraction of universities would much prefer to pay in non-pecuniaries, clinging to solving their fiscal puzzle simply by letting their gaggle of weirdo nerds hang out in their clubhouses. Here’s the rub, though: you can’t front-load non-pecuniaries. If you know you’re going to peak at 34, you’re going to want to get paid now because nobody trusts an employer to keep paying them out of “loyalty”. Just ask every professional athlete who’s ever blown out their knee how well the franchise took care of them after their elite attributes were taken from them by the dark forces of randomness and age.

So how have universities solved this quandary? By paying their very best employees a lifetime contract, an annuity bundled with all those precious non-pecuniary benefits that blessedly never show up as an expenditure in a budget.

Sure, this story applies a bit more directly to departments whose faculty enjoy outside options in the private sector and government. But still, ten years studying literature and rhetoric remains an investment in human capital with a significant opportunity cost that most universities would be loathe to compensate for in pure wages. Better again to bundle a lifetime annuity with all those non-pecuniaries, especially since the kind of people who want to study esoteric subjects with little outside market value are exactly the kind of people who are willing to even less of their total compensation in wages.

Tenure exists to balance the books in a peculiar labor market. So what happens if tenure goes away?

Well, first off universities will have to start paying more money if they want to hold their incoming labor pool historically consistent. More of those wages will have to be frontloaded as well. I have a hard time imagining the state legislature is going to increase the line item for universities to accomodate a massive increase in the wage bill. More likely the quality of talent coming in will drop, especially for technical fields.

Second, university faculty employment will become more vulnerable to the preferences of their peers, students, and to a lesser degree the state legislature. Sure, once a year some poor soul will find themselves in the crosshairs of guileless politician desperate to sacrifice an academic for media attention, but the reality is most academics will gallop unnoticed within the herd. No, the real problem will be when students decide they don’t like you. Or your colleagues decide they don’t like you. Woe unto the professor who finds themselves outside of the political zeitgeist. It’s funny to me to that politicians in Texas and North Carolina seem to think that tenure is what’s protecting liberal professors. Liberal professors are the median voter in these little quasi-democracies. It’s the conservatives who are vulnerable. Or, more accurately, the most conservative faculty member in each department.

When you imagine departments purging colleagues, what sort of department do you imagine? Chemistry? Mechanical Engineering? Marketing?

Of course not. It’s obviously a humanities-adjacent department. Which brings us to perhaps the greatest irony of eliminating tenure: it will take the biggest hotbeds of godless communist socialist conspirators and make them even more liberal.

Now, I have little doubt that universities will strategically respond with contract designs that offer quasi-tenure. They will do everything they can to reconstitute the lifetime annuity compensation structure that keeps them competitive and fiscally afloat. But you can only do so much and there seems little doubt that job security absent tenure will decline, which means wages will have to increase some, particularly for fields without the kinds of large grants for which universities are desperate.

There’s no real workaround, no panacea for losing job security that protects you from political and intellectual isolation. Perhaps the biggest effect of eliminating tenure will be to make faculties more homogenous, more paranoid, more boring, and yes, I’m talking to you state legislatures, more liberal. Eliminating tenure will, at the margin push the most valuable, most talented, and most conservative faculty away, from red states to blue states. Those left behind will, at the margin, focus more on teaching than research, activism than grants, politics than science. When red states eliminate tenure, they are taking a significant step towards conjuring exactly the bogeyman that has thus far only existed in their imagination: an institution dedicated towards indocrinating students into a monolithic political worldview contrary to their own.

When your grandchildren come home from college, they’ll explain that is what we call “ironic“.