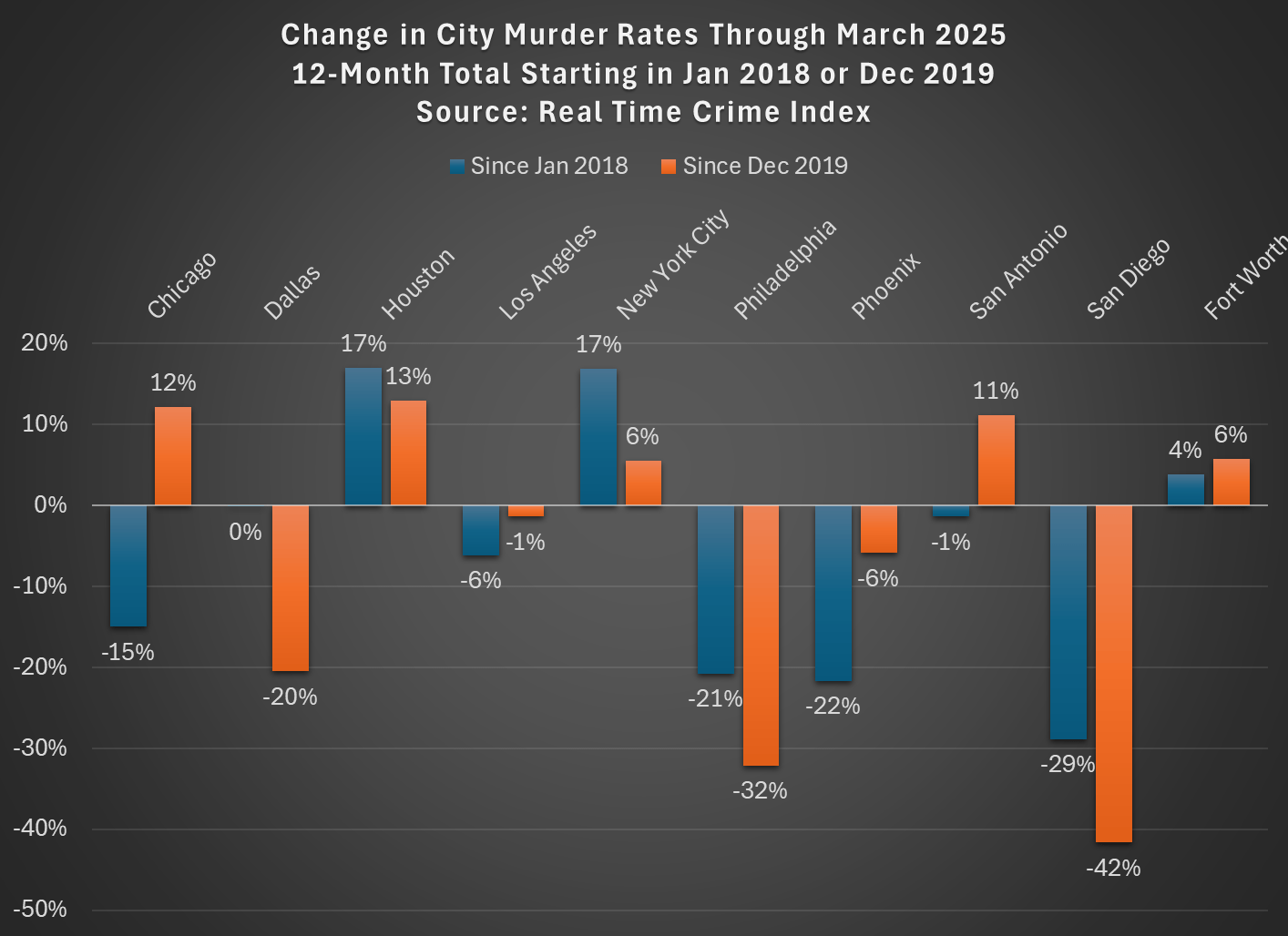

We all know that homicides spiked in the US in 2020 and we all (hopefully) know that homicides have been falling across most of the country dramatically since the end of 2021. But have homicides started to get back to, or even below, pre-pandemic levels? Or is it merely reversing the 2020 increases?

The answer depends on the city and the pre-pandemic baseline! The chart below shows the 10 largest cities (with Fort Worth instead of Jacksonville, because the Real-Time Crime Index doesn’t include the latter) in the US, using a base of either January 2018 (the first month in the RTCI) or December 2019 (just before the pandemic, and murders had fallen nationally between these two dates):

The murder data comes from the Real-Time Crime Index, and it is a 12-month total so we shouldn’t have to worry about seasonality even though the months are different. I use Census annual city population estimates to calculate the rates (and estimate 2025 based on the growth from 2023-24).

As you can see, depending on the base timeframe used, about half of the cities saw declines, a few were roughly flat, and some definitely saw increases. New York, Houston, and Fort Worth are definitely still elevated. Los Angeles, Philly, Phoenix, and San Diego are definitely down. The others are either close to even or mixed depending on your baseline.

Keep in mind these data are only through March 2025. As both Billy Binion at Reason and Jeff Asher have both recently emphasized, if we use the most recent data for many cities, it’s entirely possible that 2025 will end up having some of the lowest homicide rates ever recorded for many US cities. The declines in early 2025 have definitely been big, but mostly they are just a continuation of the post-2021 decline.

Again, for clarification, all of these cities are down from their 2020-21 peaks: using September 2021 as the base (when the national murder rate roughly peaked), these 10 cities are down between 31% and 58%. Big improvements!