The subjects of two of our posts from 2023 are suddenly big stories.

First, here’s how I summed up New Orleans’ recovery from hurricane Katrina then:

Large institutions (university medical centers, the VA, the airport, museums, major hotels) have been driving this phase of the recovery. The neighborhoods are also recovering, but more slowly, particularly small business. Population is still well below 2005 levels. I generally think inequality has been overrated in national discussions of the last 15 years relative to concerns about poverty and overall prosperity, but even to me New Orleans is a strikingly unequal city; there’s so much wealth alongside so many people seeming to get very little benefit from it. The most persistent problems are the ones that remain from before Katrina: the roads, the schools, and the crime; taken together, the dysfunctional public sector.

The New York Times had a similar take yesterday:

Today, New Orleans is smaller, poorer and more unequal than before the storm. It hasn’t rebuilt a durable middle class, and lacks basic services and a major economic engine outside of its storied tourism industry…. New Orleans now ranks as the most income-unequal major city in America…. In areas that attracted investment — the French Quarter, the Bywater and the shiny biomedical corridor — there are few outward signs of the hurricane’s impact. But travel to places like Pontchartrain Park, Milneburg and New Orleans East that were once home to a vibrant Black middle class, and there are abandoned homes and broken streets — entire communities that never regained their pre-Katrina luster…. Meanwhile, basic city functions remain unreliable.

I wrote in 2023 about a then-new Philadelphia Fed working paper claiming that mortgage fraud is widespread:

The fraud is that investors are buying properties to flip or rent out, but claim they are buying them to live there in order to get cheaper mortgages…. One third of all investors is a lot of fraud!… such widespread fraud is concerning, and I hope lenders (especially the subsidized GSEs) find a way to crack down on it…. This mortgage fraud paper seems like a bombshell to me and I’m surprised it seems to have received no media attention; journalists take note. For everyone else, I suppose you read obscure econ blogs precisely to find out about the things that haven’t yet made the papers.

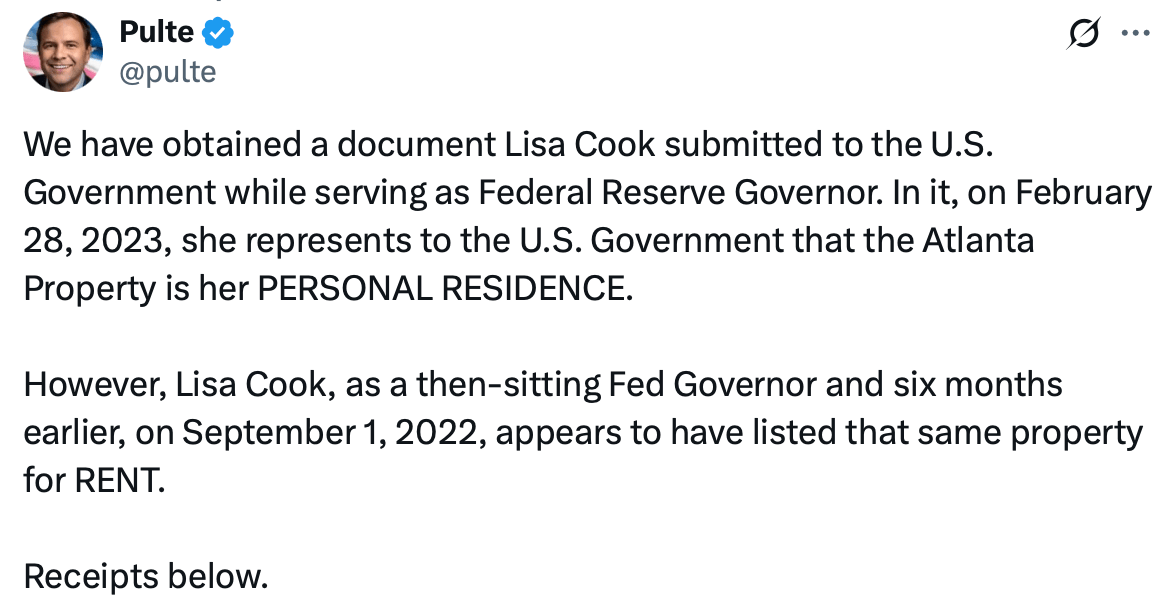

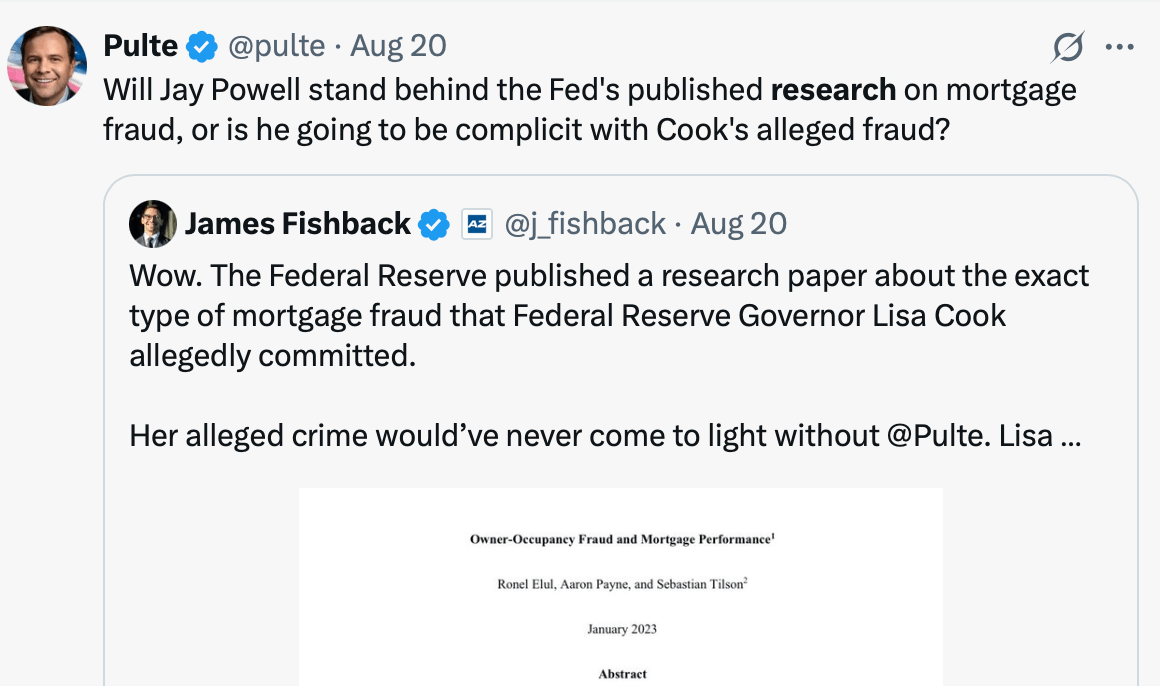

Well, that paper has now got its fair share of attention from the media and the GSEs. Bill Pulte, director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency and chairman of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, has been going after Biden-appointed Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook over allegations that she mis-stated her primary residence on a mortgage application:

Pulte has written many dozens of tweets about this, at least one of which cited the Philly Fed paper:

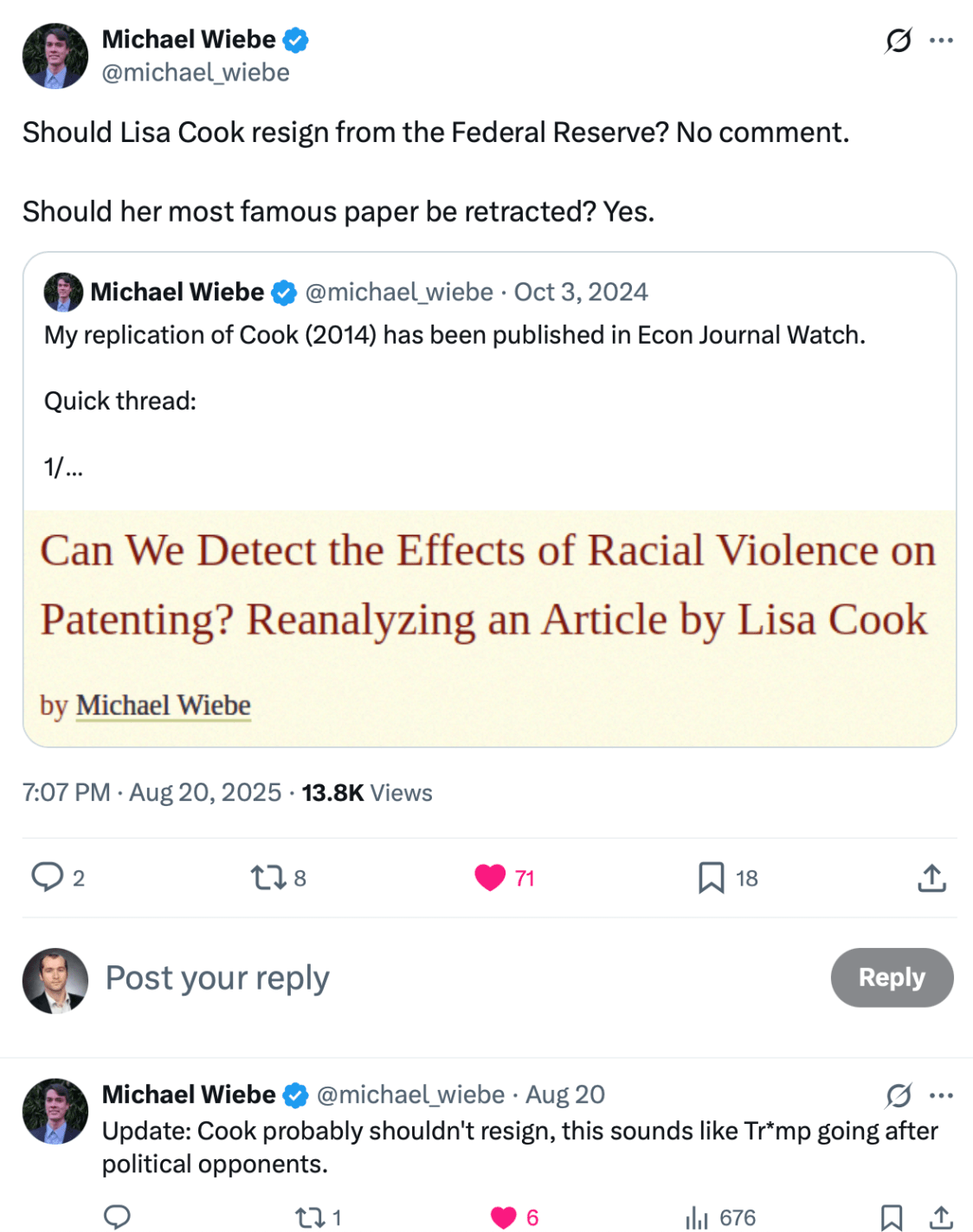

Now President Trump is trying to fire Cook. Federal Reserve Governors can only be fired “for cause” and none ever have been, but Trump is using this alleged mortgage fraud to try to make Cook the first.

The Trump administration seems to have made the same realization as Xi Jinping did back in 2012– that when corruption is sufficiently widespread, some of your political opponents have likely engaged in it and so can be legally targeted in an anti-corruption crackdown (while corruption by your friends is overlooked).

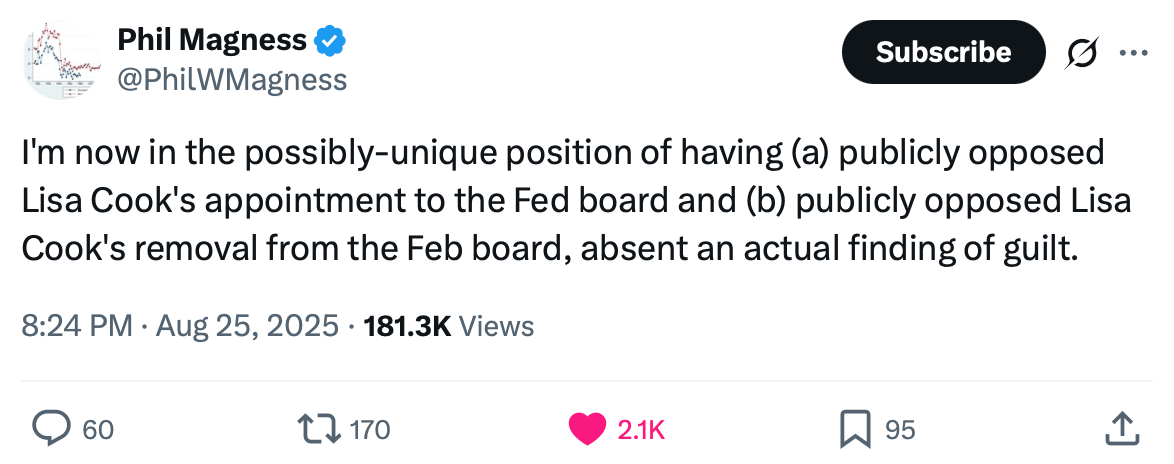

I’m one of a few people hoping for the Fed to be run the most competent technocrats with a minimum of political interference:

But I’m not expecting it.

Remember, you read it here first.