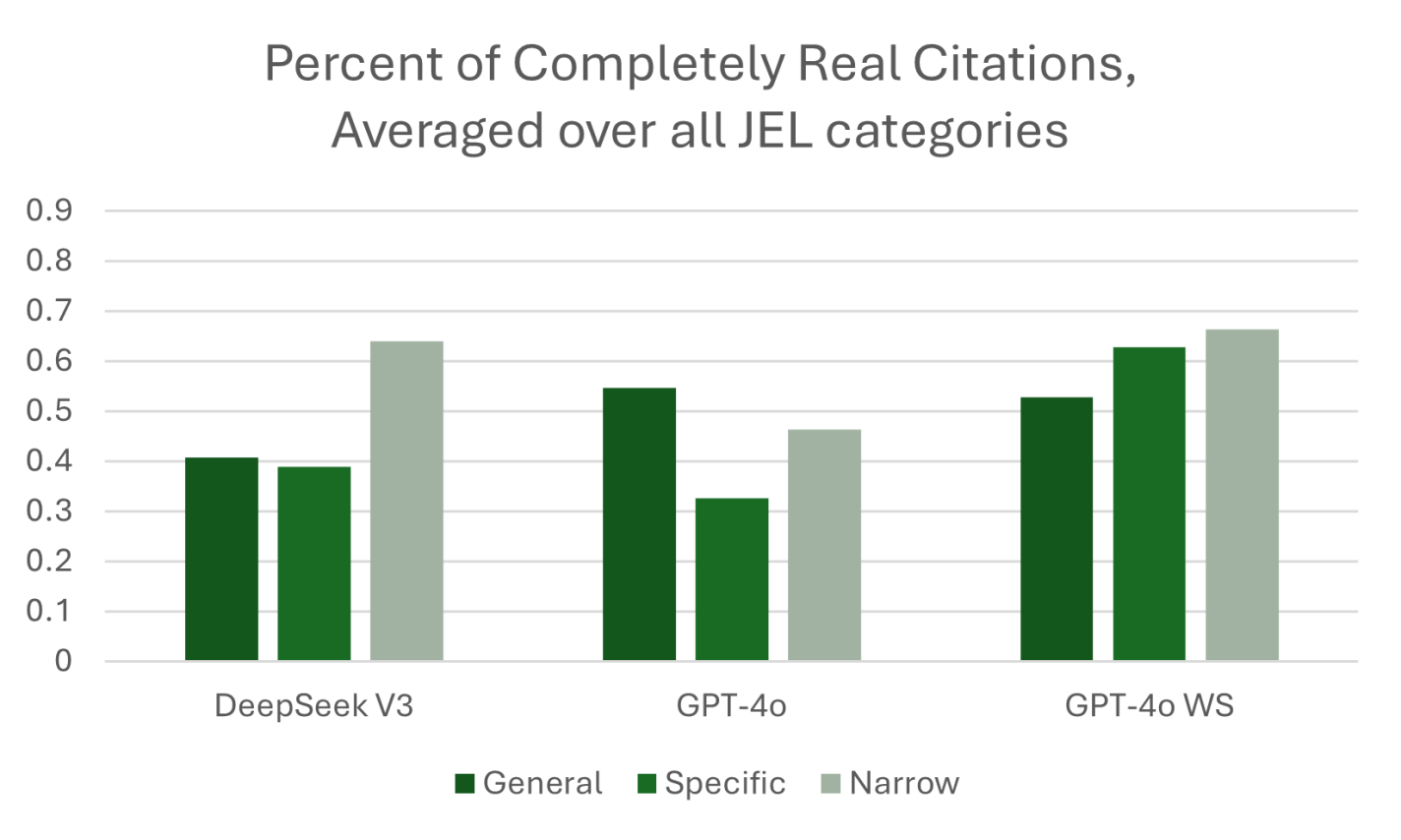

In 2023, we gathered the data for what became “ChatGPT Hallucinates Nonexistent Citations: Evidence from Economics.” Since then, LLM use has increased. A 2025 survey from Elon University estimates that half of Americans now use LLMs. In the Spring of 2025, we used the same prompts, based on the JEL categories, to obtain a comprehensive set of responses from LLMs about topics in economics.

Our new report on the state of citations is available at SSRN: “LLM Hallucination of Citations in Economics Persists with Web-Enabled Models”

What did we find? Would you expect the models to have improved since 2023? LLMs have gotten better and are passing ever more of what used to be considered difficult tests. (Remember the Turing Test? Anyone?) ChatGPT can pass the bar exam for new lawyers. And yet, if you ask ChatGPT to write a document in the capacity of a lawyer, it will keep making the mistake of hallucinating fake references. Hence, we keep seeing headlines like, “A Utah lawyer was punished for filing a brief with ‘fake precedent’ made up by artificial intelligence”

What we call GPT-4o WS (Web Search) in the figure below was queried in April 2025. This “web-enabled” language model is enhanced with real-time internet access, allowing it to retrieve up-to-date information rather than relying solely on static training data. This means it can answer questions about current events, verify facts, and provide live data—something traditional models, which are limited to their last training cutoff, cannot do. While standard models generate responses based on patterns learned from past data, web-enabled models can supplement that with fresh, sourced content from the web, improving accuracy for time-sensitive or niche topics.

At least one third of the references provided by GPT-4o WS were not real! Performance has not significantly improved to the point where AI can write our papers with properly incorporated attribution of ideas. We also found that the web-enabled model would pull from lower quality sources like Investopedia even when we explicitly stated in the prompt, “include citations from published papers. Provide the citations in a separate list, with author, year in parentheses, and journal for each citation.” Even some of the sources that were not journal articles were cited incorrectly. We provide specific examples in our paper.

In closing, consider this quote from an interview with Jack Clark, co-founder of Anthropic:

The best they had was a 60 percent success rate. If I have my baby, and I give her a robot butler that has a 60 percent accuracy rate at holding things, including the baby, I’m not buying the butler.