Snowmageddon!! Over 20 inches of snow!!! That is what we in the mid-Atlantic should expect on Sat-Sun Jan 24-25 according to most weather apps, as of 9-10 days ahead of time. Of course, that kept us all busy checking those apps for the next week. As of Wednesday, I was still seeing numbers in the high teens in most cases, using Washington, D.C. as a representative location. But my Brave browser AI search proved its intelligence on Wednesday by telling me, with a big yellow triangle warning sign:

Note: Apps and social media often display extreme snow totals (e.g., 23 inches) that are not yet supported by consensus models. Experts recommend preparing for 6–12 inches as a realistic baseline, with the potential for more.

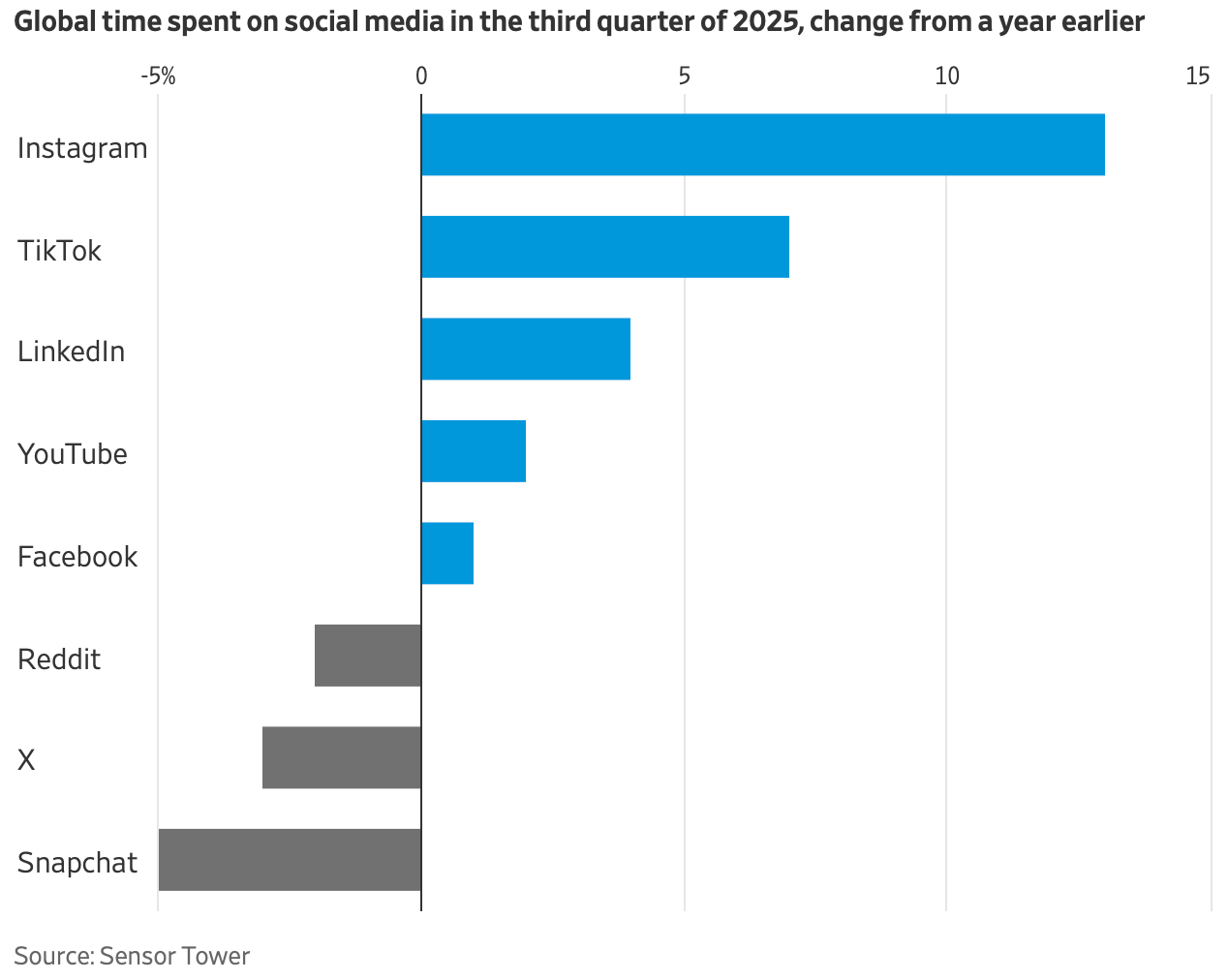

“Huh,” thought I. Well, duh, the more scared they make us, the more eyeballs they get and the more ad revenue they generate. Follow the money…

Unfortunately, I did not log exactly who said what when last week. My recollection is that weather.com was still predicting high teens snowfall as of Thursday, and the Apple weather app was still saying that as of Friday. The final total for D.C. was about 7.5 inches for winter storm Fern. In fairness, some very nearby areas got 9-10 inches, and it ended up being dense sleet rather than light fluffy snow. But there was still a pretty big mismatch.

Among the best forecasters I found was AccuWeather. They showed a short table of probabilities that centered on (as I recall) 6-10”, with some chances for higher and for lower, that let you decide whether to prepare for a low probability/high impact scenario. It seems that the Apple weather app is notoriously bad: instead of integrating several different forecast models like some other apps (and like your local talking head meteorologist), it apparently just spits out the results of one model:

The core issue is that many weather apps, including Apple Weather, display raw data from individual forecast models without the context and analysis that professional meteorologists provide. While meteorologists at the National Weather Service balance multiple computer models, dozens of simulations and their own expertise to create forecasts, apps often pull from a single source and deliver it directly to users.

“Everything that catches attention is mostly nonsense,” said Eric Fisher, chief meteorologist for WBZ-TV in Boston. He points to the viral snowfall maps that spread on social media, noting that extreme forecasts generate the most attention even when they may not be the most accurate.

Anyway, I tried to poke around and find out in dollar terms how much it benefits the weather apps to exaggerate storm dangers. I was unsuccessful there, but by playing with query wording, I was able to coax out of ChatGPT some numbers on how much these exaggerations may cost the rest of us. (A more qualitative search noted, among other things, that the “crying wolf” cost of people becoming jaded to alarmist forecasts may lead them to discount genuine warnings; and I will add it is inconvenient to find the stores out of things because of panic buying).

Everything below the line of asterisks is just a straight dump from the AI, since I could not readily improve on its presentation:

****************************************************************

The economic impact of weather apps exaggerating storm dangers isn’t easy to quantify precisely because most formal studies focus on weather warnings overall (from official sources like the National Weather Service), not specifically on private weather apps exaggerating risk. However, economics research on false alarms, over-warning, and exaggerated alerts offers concrete dollar figures that we can use to approximate the kinds of costs involved. Below are the key economic impacts with as many dollar figures as available:

💸 1. Opportunity Costs of False or Overbroad Storm Warnings

Time cost of false warnings:

- Traditional county-wide tornado warnings (over-broad alerts) have historically forced many people to shelter unnecessarily, resulting in ≈234 million person-hours per year spent under warnings (1996–2004) — valued at roughly $2.7 billion annually in lost time/productivity in the U.S. alone.

- Improved storm-based warnings that reduce false warning area could save up to $750 million–$1.9 billion/year in avoided lost time.

This demonstrates that exaggerated alerts — such as those sometimes amplified or presented without clear context by weather apps — can force unnecessary economic shutdowns of work and business activity.

🏙️ 2. Evacuation and Preparedness Costs from False Alarms

Evacuation costs:

- A NOAA analysis estimates that evacuation costs for hurricanes, when done broadly for storm-warnings, can reach about $1.4 billion annually in the U.S., with roughly $1 billion being unnecessary cost due to false alarms (people evacuating where no damaging winds ultimately occur).

Evacuations are one of the most expensive forms of response — from lost wages to lodging and fuel costs — and exaggerated risk messaging can trigger them prematurely or more frequently.

🏭 3. Business Productivity Losses from False Alerts

Example from private sector:

- A building management firm reported that by reducing false storm alerts (better targeted data rather than broad app warnings), it saved ~$10 million in lost production time in one year alone.

This is a real dollar example showing how over-warning impacts businesses directly when they preemptively shut down operations.

💼 4. Broader Firm-Level Economic Avoidance

Cost avoidance from better warning info:

- A study of nearly 500 firms found that switching from deterministic (binary “storm/no storm”) warnings to probabilistic information could produce $2.3 billion to $7.6 billion per year in avoided costs for businesses, thanks to better decision-making.

While this doesn’t measure exaggeration specifically, it underscores the economic penalty of imprecise or alarmist warnings, which many weather apps unintentionally echo.

📉 5. Insurance & Property Impacts

Although not directly about exaggerated warnings, inaccurate perceptions of storm danger influence behavior and pricing:

- Insurance premiums rising: In storm-prone states (e.g., Florida), homeowners’ premiums have risen by ~57% or more because of risk perceptions and loss patterns tied to severe weather.

- Losses from storms: Billion-dollar disasters are common; for example, Hurricane Milton in 2024 had estimated total costs of $21–$85 billion (depending on source).

While not directly caused by exaggeration, inflated perceptions of danger (from apps or media) can affect insurance markets and property values, contributing indirectly to economic impacts.

📈 6. Net Benefits vs. Exaggeration

It’s important to balance:

- Early warnings overall clearly save money and lives. Improved forecasts and early alert systems have been estimated to avoid $300 million to $2 billion per year in asset losses and provide up to $32 billion/year in broader economic benefits (through optimized activities and prep).

This highlights that the problem isn’t warnings per se, but inaccurate or exaggerated warnings that cause over-response.