A black swan is a crisis that comes out of nowhere. A gray rhino, by contrast, is a problem we have known about for a long time, but can’t or won’t stop, that will at some point crash into a full-blown crisis.

The US national debt is a classic gray rhino. The problem has slowly been getting worse for 25 years, but the crisis still seems far enough off that almost no one wants to incur real costs today to solve the problem. During the 2007-2009 financial crisis and the 2020-2021 Covid pandemic we had good reasons to run deficits. But we’ve ignored the Keynesian solution of paying back the deficits incurred in bad times with surpluses in good times.

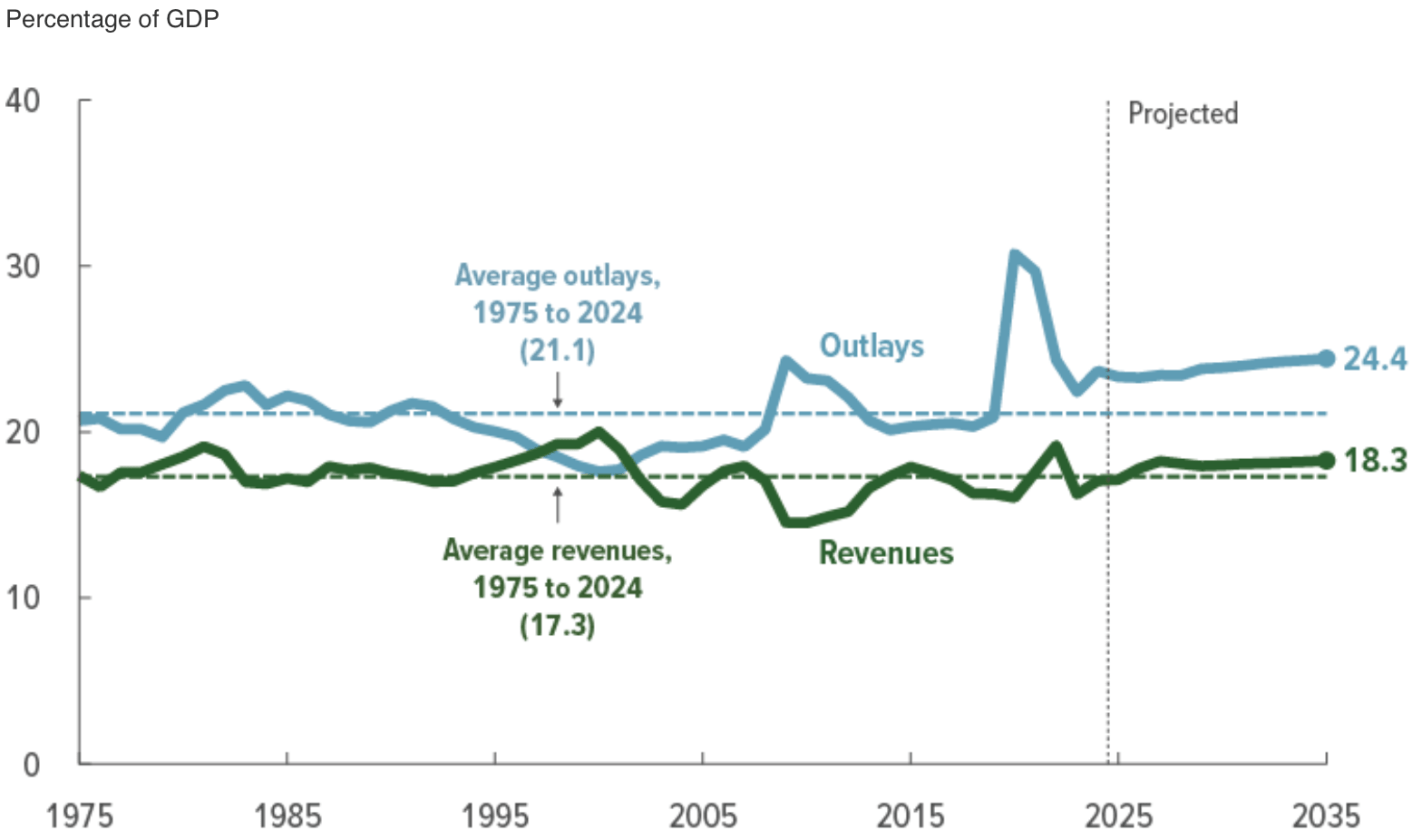

We are currently in reasonably good economic times, but about to pass a mega-spending bill that blows the deficit up from its already-too-high-levels. At a time when we should be running a surplus, we are instead running a deficit around 6% of GDP:

Our ‘primary deficit’ is lower, a more manageable 3% of GDP. But if interest rates go higher, either for structural reasons or because of a loss of confidence in the US government’s willingness to pay its debts, the total deficit could spiral higher rapidly. The CBO optimistically assumed that the interest rate on 10-year treasuries will fall below 4% in the 2030s, from 4.3% today:

But their scoring of H.R. 1 (“One Big Beautiful Bill Act”) shows it adding $3 trillion to the debt over the next 10 years, increasing the deficit by ~1% of GDP per year.

I already suspected this gray rhino would eventually cause a crisis, but this bill and the milieu that produced turn it into a near guarantee- nothing stops the deficit train until we hit a full blown crisis. That crisis is no longer just a long-term issue for your kids and grandkids to worry about- you will see it in 7 years or so. Unfortunately, that is still far enough away that current politicians have no incentive to take costly steps to avoid it. In fact, deficits will probably make the economy stronger for a year or two before they start making things worse- convenient for all the Congresspeople up for election in less than 2 years.

Here are the ways I see this playing out, from most to least likely:

- By around 2032, either the slowly aging population or a sudden spike in interest rates forces the government to touch at least one of the third rails of American politics: cut Social Security, cut Medicare, or substantially raise taxes on the middle class (explicitly or through inflation).

- We get bailed out again by God’s Special Providence for fools, drunks, and the United States of America. AI brings productivity miracles bigger than those of computers and the internet, letting GDP grow faster than our debts.

- We default on the national debt (but this is a risky option because we will still want to run big deficits, and lenders will only lend if they expect to get paid back).

- We do all the smart policy reforms that economists recommend in time to head off the crisis and stop the rhino. Medical spending falls without important services being cut thanks to supply-side reforms or cheap miracle drugs (GLP-1s going off patent?).

I’m hoping of course for numbers 2 and 4, but after this bill I’m expecting the rhino.