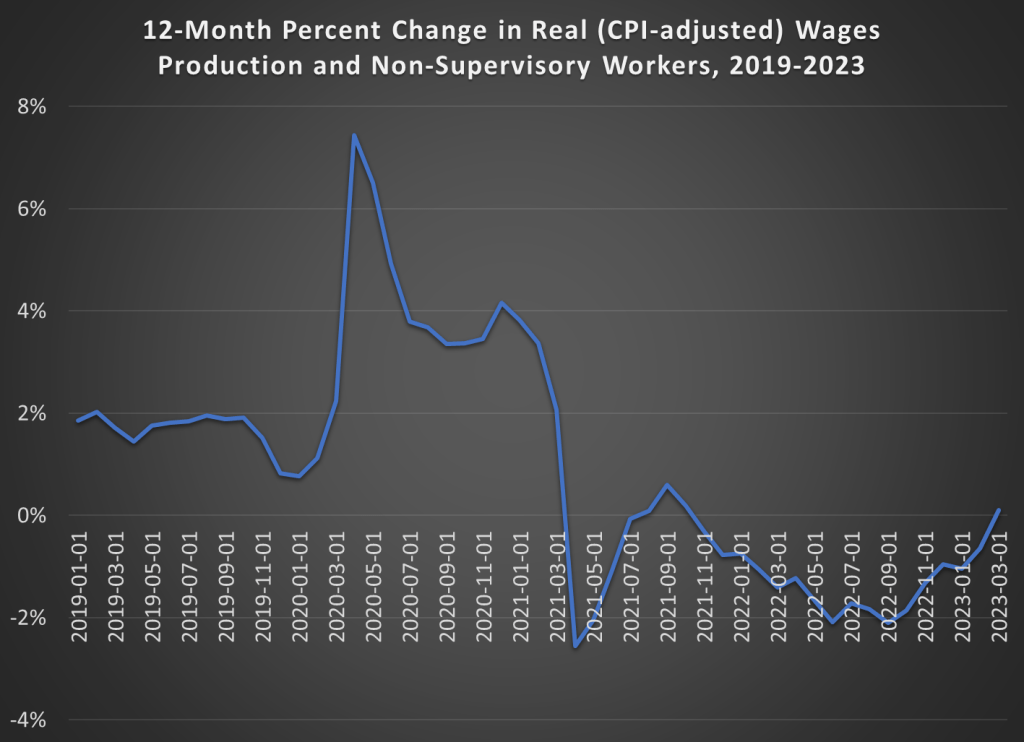

Last week I wrote an optimistic take on inflation. The rate of general price inflation has fallen a lot in recent months, and wage growth is now clearly outpacing inflation. That’s all good news.

Today, the Fed will announce their latest interest rate decision. Will the good news on inflation lead the Fed to stop raising interest rates? I’m not very good at making predictions, but today I’ll give a pessimistic take on inflation which suggests the Fed (and everyone else) should still be concerned about inflation.

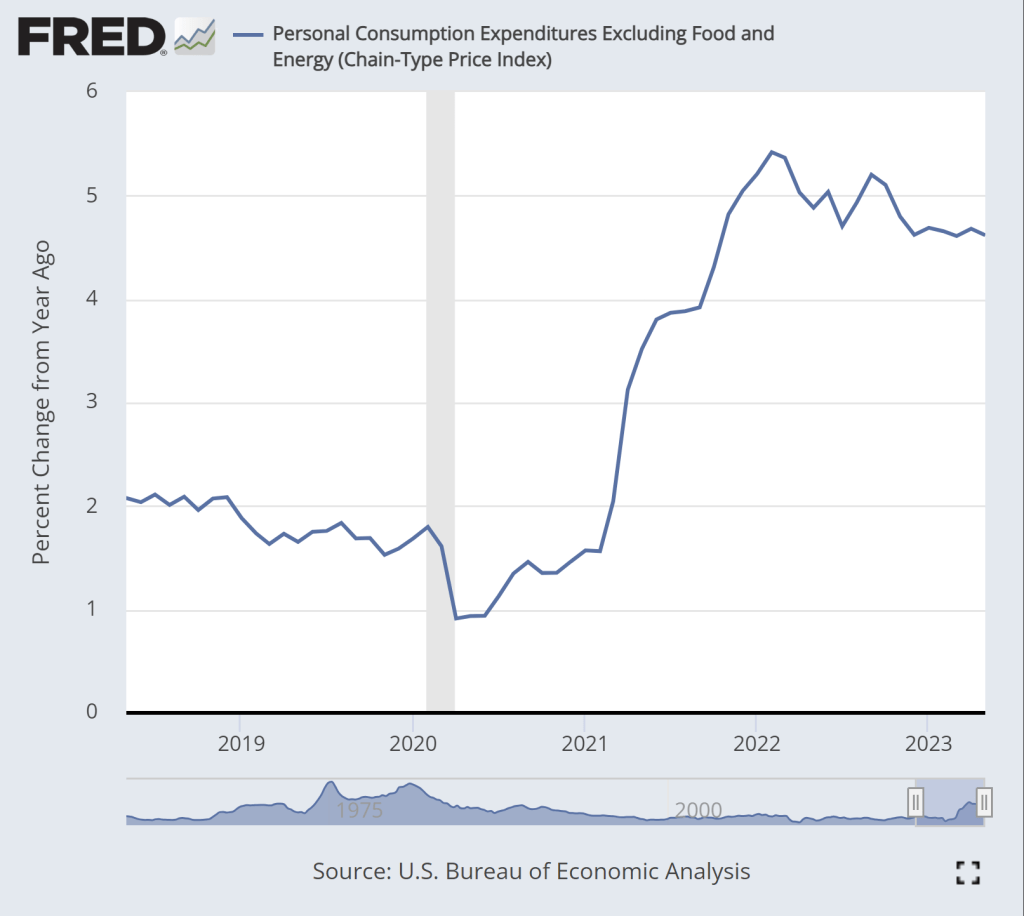

The pessimistic take can be summarized in two charts. First, this chart shows the year-over-year change in the core PCE inflation index. As most readers will know, core indexes take out food and energy prices. This is not a “cheat” to mask important goods, it’s done because these are particularly volatile categories of goods. If we want to see the true underlying trend in inflation, we should ignore price fluctuations that are driven largely by weather and geopolitics.

While there is some moderation in inflation in this chart, we don’t see anything like the dramatic decline in the CPI-U, which fell from about 9 to 3 percent over roughly the past year. True, there is some decline over the past year, but only about 1 percentage point, and it has been stuck at just over 4.6 percent for the past 6 months. This is not a return to normalcy, as this rate historically has stayed in the band of 1-2 percent.

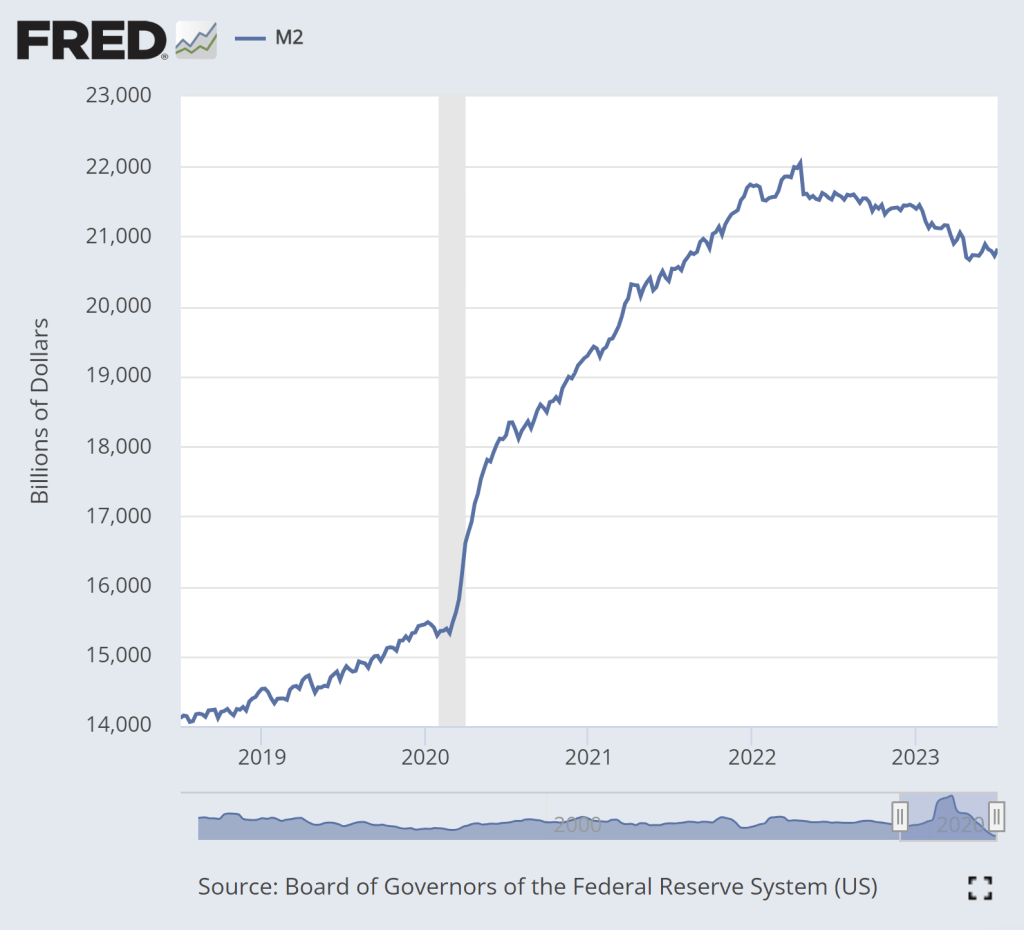

The second pessimistic chart is M2, a broad measure of the money supply.

The dramatic increase in M2 during 2020 is clear. That’s a big source of the inflation issues we’ve had over the past 2 years. There is some cause for optimism in this chart: M2 has clearly shrunk from the peak in Spring 2022. In fact, using a year-over-year percentage change, M2 has been negative since last November.

But if we look very recently, there is less cause for optimism. Since late April, M2 has stopped falling. In fact, it’s up a little bit. Is this a sign that the Fed doesn’t really have inflation under control? Perhaps. The increase isn’t huge, and there’s always some seasonality and noise to this data so we shouldn’t overanalyze this small deviation from the general decline in the past year plus. But we’ll need to continue watching this data.