“Sticky Prices as Coordination Failure: An Experimental Investigation” is my new paper with David Munro of Middlebury, up at SSRN.

We ask whether coordination failures are a source of nominal rigidities. This was suggested in a recent speech by ECB President Christine Lagarde. She said, “In the recent decades of low inflation, firms that faced relative price increases often feared to raise prices and lose market share. But this changed during the pandemic as firms faced large, common shocks, which acted as an implicit coordination mechanism vis-à-vis their competitors.”

Coordination failure was suggested as a possible cause of price rigidity in a theory paper by Ball and Romer (1991). They demonstrated the possibility for multiple equilibria, and we perform the first laboratory test to observe equilibrium selection in this environment.

We theoretically solve a monopolistically competitive pricing game and show that a range of multiple equilibria emerges when there are price adjustment costs (menu costs). We explore equilibrium selection in laboratory price setting games with two treatments: one without menu costs where price adjustment is always an equilibrium, and one with menu costs where both rigidity and flexibility are possible equilibria.

In plain language, for our general audience, the idea is that the prices you set might depend on what other people are doing. If other people are responding to a shock (for example, Covid driving up labor costs all over town might cause retail prices to rise) then you will, too. If every other store in town is afraid to raise prices, then there is a certain situation where you might resist adjusting your prices, too (price rigidity).

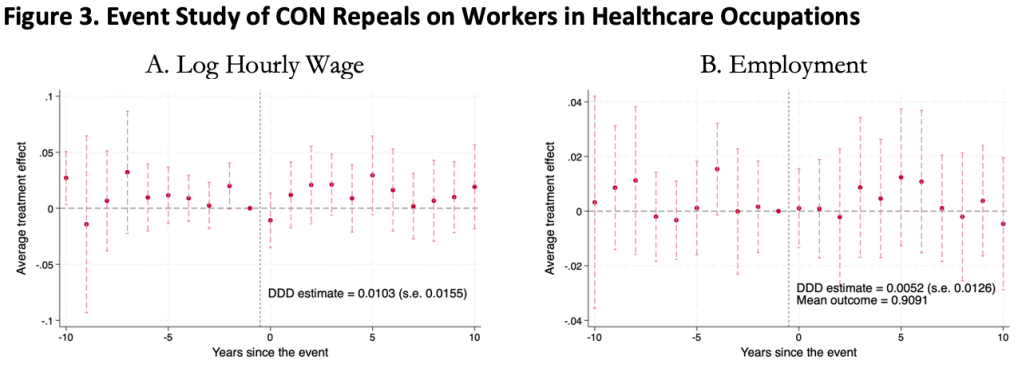

Results: First, when there is only one theoretical equilibrium, subjects usually conform to it. When cost shocks are large, price adjustment is a unique equilibrium regardless of the presence of menu costs, and we see that subjects almost always adjust prices. When cost shocks are small and there are menu costs rigidity is a unique equilibrium and subjects almost never adjust. Conversely, with small cost shocks subjects almost always adjust when there are no menu costs.

The more interesting cases are when the parameters allow for either rigidity or flexibility to be selected. We find that groups do not settle at the rigidity equilibrium. Rather, depending on the specific nature of the shock, between half and 80% of subjects adjust in response to a shock. The intermediate levels of adjustment are represented here in this figure as the red circles that fall between the red and green bands where multiple equilibria are possible.

In the figure above, the red circles are higher when the production cost shock gets further from zero in absolute value. We see that the proportion of subjects adjusting prices is proportional to the size of the cost shocks. This is consistent with the interpretation that the large post-COVID cost shocks acted as an implicit coordination mechanism for firms raising prices. Our results provide a number of interesting insights on nominal rigidities. We document more nuance in the paper regarding heterogeneity and asymmetry. Comments and feedback are appreciated! If it’s not clear from the EWED blog how to email me (Joy), find my professional contact info here.