41 states now require students to take a course in economics or personal finance in order to graduate high school:

12 states representing 21% of US high schoolers passed mandates for personal finance classes just since 2022. This sounds like a good idea that will enable students to navigate the modern economy. But does it work in practice?

A 2023 working paper “Does State-mandated Financial Education Affect Financial Well-being?” by Jeremy Burke, J. Michael Collins, and Carly Urban argues that it does, at least for men:

We find that the overall effects of high school financial education graduation requirements on subjective financial well-being are positive, between 0.75 and 0.80 points, or roughly 1.5 percent of mean levels. These overall effects are driven almost entirely by males, for whom financial education increases financial well-being by 1.86 points, or 3.8 percent of mean financial well-being.

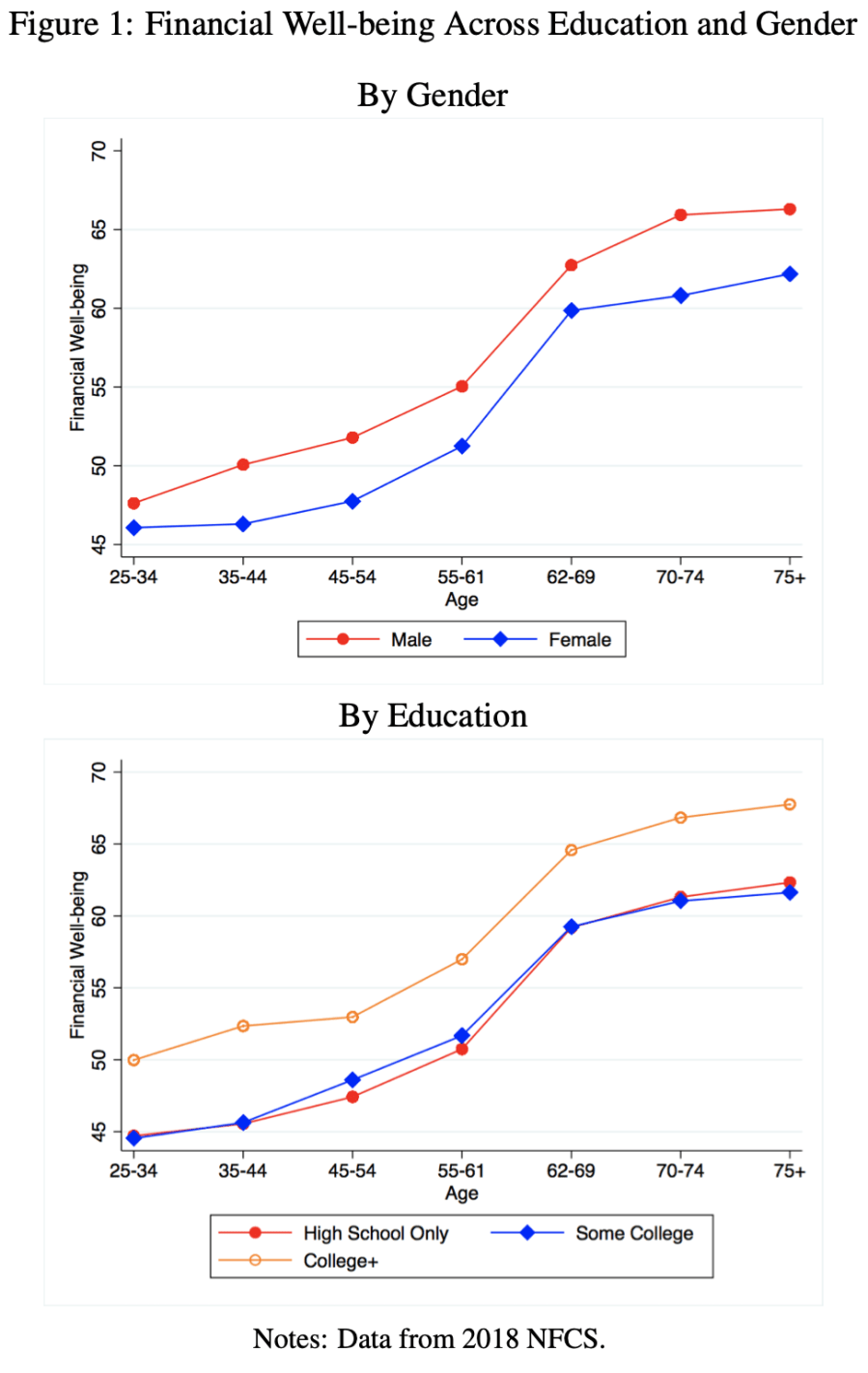

The paper has nice figures on financial wellbeing beyond the mandate question:

As soon as I heard about the rapid growth in these mandates from Meb Faber and Tim Ranzetta, I knew there was a paper to be written here. I was glad to see at least one has already tackled this, but there are more papers to be written: use post-2018 data to evaluate the new wave of mandates, evaluate the economics mandates in addition to the personal finance ones, and use a more detailed objective measure like the Survey of Consumer Finances.

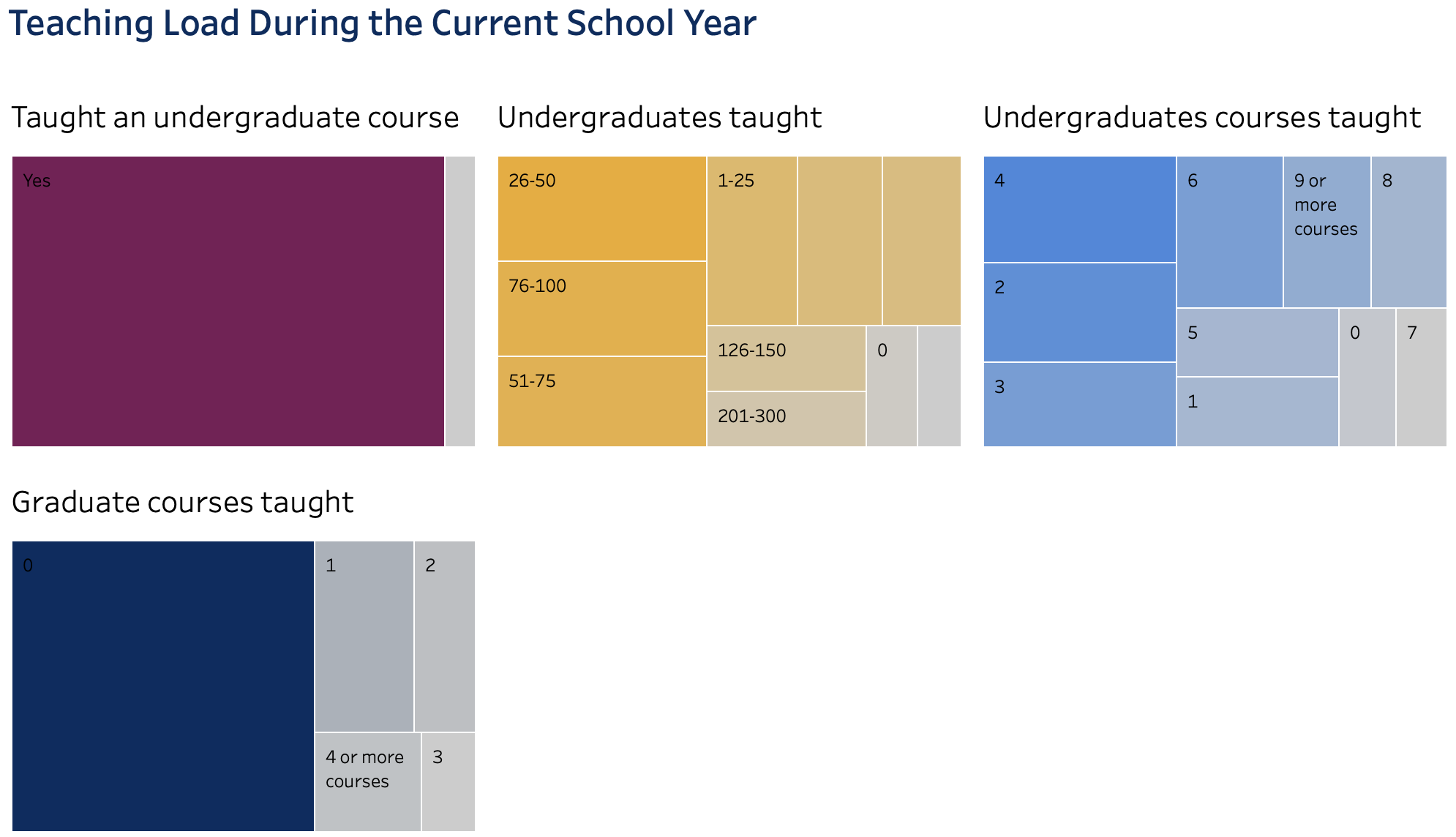

There’s also more to be done in practice, hiring and training the teachers to offer these new classes:

our estimates are likely attenuated due to poor compliance by schools subject to new financial education curriculum mandates. Urban (2020) finds evidence that less than half of affected schools may have complied. As a result, our estimated overall and differential effects may be less than half the true effects