This is the third in a series of occasional blog posts on individual initiatives that made a strategic (not just tactical) difference in the course of the second world war.

World War II was not only the biggest, bloodiest conflict, in human history. It played a definitive role in giving us the world we have today. Everyone can find something to complain about in the current state of affairs, but think for a moment what the world would be like if the Axis powers had prevailed.

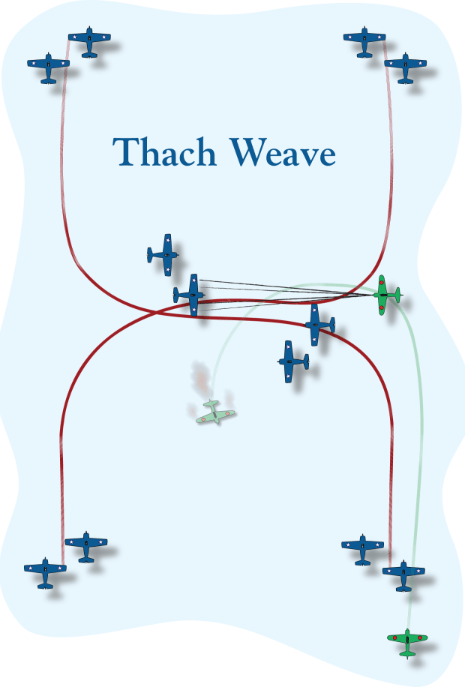

Having control of the air became crucial in the second world war. It meant you could drop bombs on enemy soldiers, ships, tanks, cities, factories, etc., etc. The Germans showed early on how important that can be. Their terror bombing of the Dutch city of Rotterdam compelled the Netherlands to surrender to spare other cities from being likewise bombed, even though the Dutch armed forces could have held out for some time longer. The German breakthrough in their invasion of France in 1940 was facilitated by a concentrated Stuka dive bombing attack on a key sector of the French front lines. The 1940 Battle of Britain was an air war, where the Germans hoped to whittle the British Air Force capability down enough to permit them to invade across the English Channel. And so on.

The main German fighter plane at first was the Messerschmidt Me 109. It was a good plane, although by 1941 the British Spitfire had become a match for it. Both the Me 109 and the Spitfire were designed around in-line engines, where the cylinders were arranged in two long rows in the engine block. That gave a narrow engine, and hence a skinny profile to the airplane, which tended to reduce wind resistance and make for higher speeds. A weak point of all in-line engines is that they need to have a circulating coolant system, going through a radiator, to cool down the engine block from the heat of the internal combustion. This makes for more complicated maintenance and is very vulnerable to being damaged by enemy fire,

Just when the Brits were starting to wrest air superiority back from the Germans, the FW 190 appeared in the skies over France. Allied pilots were shocked. The new German fighter could out-climb, out-roll, and in many cases out-fight the current Spitfire models. This so-called “butcher bird” gave air superiority back to the Germans.

Its remarkable performance was the result of one man’s engineering philosophy and persistence: Kurt Tank, chief designer at the German aircraft manufacturer Focke-Wulf. Tank was a pilot as well as an engineer, with long and varied prior military experience. He chose a radial engine for his plane, to make it more rugged and easy to maintain. With a radial engine, the individual cylinders all stick out from a central crankcase; airflow past the fins on the cylinders cools the engine. Hence, no vulnerable cooling system and radiator. The conventional thinking was that a radial engine was so fat that an airplane using it would have a wide, draggy profile. His ingenious design features allowed him to make a fast, agile plane. However, was an uphill job for Tank to sell his concept to the German military establishment. Eventually, his results spoke for themselves and the Fw 190 was produced. With its critical spots armored, the Fw 190 was hard to kill. Tank deliberately gave a wide stance and long travel to the landing gear, to allow deployment in rough frontline airfields.

The Fw 190 was a superb low-medium altitude fighter, and was also widely pressed into service (due to its rugged design) as a precision bomber on the front lines. Around 20,000 Fw 190s were produced. They shot down many thousands of Allied planes, killed untold thousands of Allied airmen and soldiers, and destroyed thousands of Allied vehicles, mainly on the Eastern Front. It was not enough to change the ultimate outcome of the war, but Tank stretched it out appreciably, by (largely single-handedly) giving the Germans such a versatile and deadly weapon.