Rare earths are a set of 17 metals with properties which make them essential to a swathe of high-tech products. These products include lasers, LEDs, catalysts, batteries, medical devices, sensors, and above all, magnets. Rare earth magnets are used in electric motors and generators and vibrators, making them essential to electric cars, wind turbine generators, cell phones/tablets/computers, airplanes, phones, and all sorts of military devices.

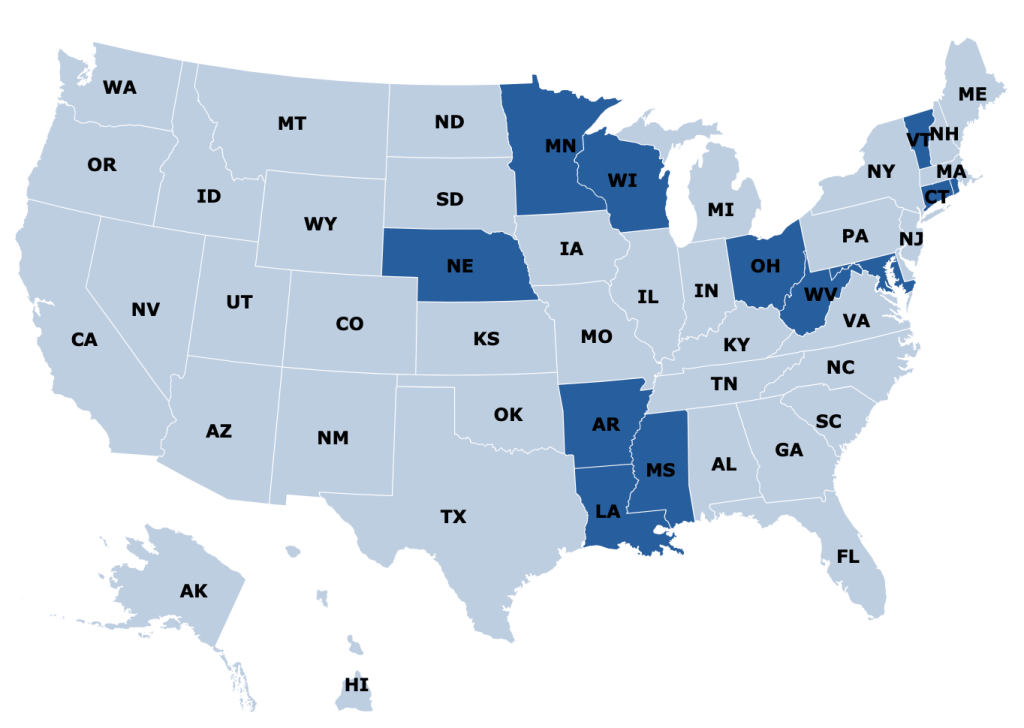

China happens to have large amounts of rare earth oxide ores for mining, relatively lax environmental standards, and a large, compliant workforce. The Chinese government has harnessed these resources to make the nation by far the largest producer of rare earths. Their massive, relatively low-cost production has suppressed production in other countries. This has been a conscious policy, to achieve global control over a vital raw material.

The first time China used this effective monopoly as a political weapon was in a maritime dispute with Japan in 2010. China cut off exports of rare earth metals to Japan for two years, crimping the Japanese electronics industry. Other nations took note of this threat, and since then have been a number of half-hearted (in my opinion) efforts in various Western nations to develop some domestic capacity and to redesign motors to reduce dependence on rare earth materials.

China’s share of rare earth ore mined is down to 60%, but they totally dominate processing the ore to metals, and subsequent fabrication of magnets from the metal. Nearly all of the ore mined in the U.S. is shipped over to China for processing, mainly because of environmental regulations here.

According to the Asia Times,

The PRC still dominates the entire vertical industry and can flood global markets with cheap material, as it has done before with steel and with solar panels. In 2022, it mined 58% of all rare earths elements, refined 89% of all raw ore, and manufactured 92% of rare earths-based components worldwide.

There is no other global industry so concentrated in the hands of the Chinese Communist Party, nor with such asymmetric downstream impact, as rare earths.

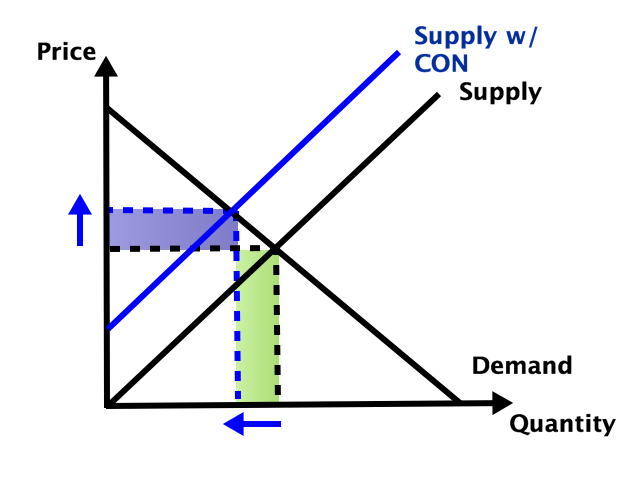

It seems the only way for the West to blunt the Chinese monopoly in rare earths is with large, long-term subsidies (since the Chinese can always undersell the rest of the world on a free market basis) and probably some pushing past environmental objections.

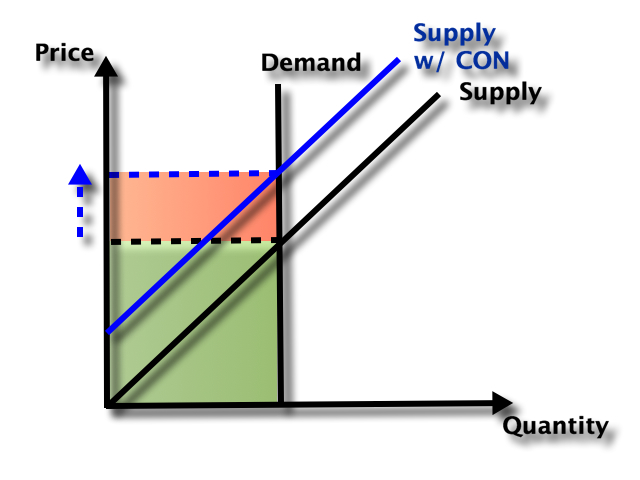

Alarmed by the rapid buildup of Chinese military forces (towards a possible invasion of Taiwan), the U.S. and its allies have begun restricting exports of the highest-power silicon chips to China. In retaliation, China has reportedly made plans to restrict exports of rare earths, starting in 2023. If they follow through, that move would crush fabrication of magnets and of magnet-dependent devices like motors and generators in other countries; the rest of the world would have to come crawling to China for all these items.

This move would in turn cause the rest of the world to accelerate its plans to produce rare earths outside China, but there would be several years of great disruption, and Chinese-made final devices like motors and generators would always have a huge price advantage, due to their cheaper raw material inputs.

I suspect there may be a high-stakes game of brinksmanship going on behind the scenes. The Chinese leadership presumably knows that they can only play this rare earth export ban card once, and the West does not really want to plow a lot of resources into producing large amounts of rare earths much more expensively than they can be bought from China. So maybe we will see some relaxation in chip export controls for China in exchange for them not pulling the final trigger on a rare earth export ban.

We live in interesting times.