The Olympics have begun. Is there anything economists can say about what determines a country’s medal count? You might not think so, but the answer is a clear yes! In fact, I am going to say that both the average economist and the average political economist (in the sense of studying political economy) have something of value to say.

Why could they not? After all, investing efforts and resources in winning medals is a production decision just like using labor and capital to produce cars, computers or baby diapers. Indeed, many sports cost thousand of dollars in equipment alone each year – a cost to which we must add the training time, foregone wages, and coaching. Athletes also gain something from these efforts – higher incomes in after-career, prestige, monetary rewards per medal offered by the government. As such, we can set up a production function of a Cobb-Douglas shape

Where N is population, Y is total income (i.e., GDP), A is institutional quality and T is the number of medals being won. The subscript i and t depict the medals won at any country at any Olympic-event. This specification above is a twist (because I change the term A’s meaning as we will see below) on a paper in the Review of Economics and Statistics published in 2004 by Andrew Bernard and Meghan Busse.

The intuition is simple. First, we can assume that Olympic-level performance abilities requires a certain innate skill (e.g. height, leg length). The level required is an absolute level. To see this, think of a normal distribution for these innate skills and draw a line near the far-right tail of the distribution. Now, a country’s size is directly related to that right-tail. Indeed, a small country like Norway is unlikely to have many people who are above this absolute threshold. In contrast, a large country like Germany or the United States is more likely to have a great number of people competing. That is the logic for N being included.

What about Y? That’s because innate skill is not all that determines Olympic performance. Indeed, innate skills have to be developed. In fact, if you think about it, athletes are less artists who spend years perfecting their art. The only difference is that this art is immensely physical. The problem is that many of the costs of training for many activities (not all) are pretty even across all income levels. Indeed, many of the goods used to train (e.g., skis, hockey sticks and pucks, golfing equipment) are traded internationally so that their prices converge across countries. This tends to give an edge to countries with higher income levels as they can more easily afford to spend resources to training. This is why Norway, in spite of being quite small, is able to be so competitive – its quite-high level of income per capita make it easier to invest in developing sporting abilities and innate talent.

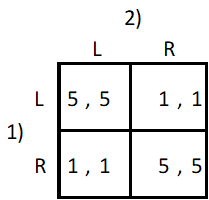

Bernard and Busse confirm this intuition and show that, yes, population and development levels are strong determinants of medal counts. The table below, taken from their article, shows this.

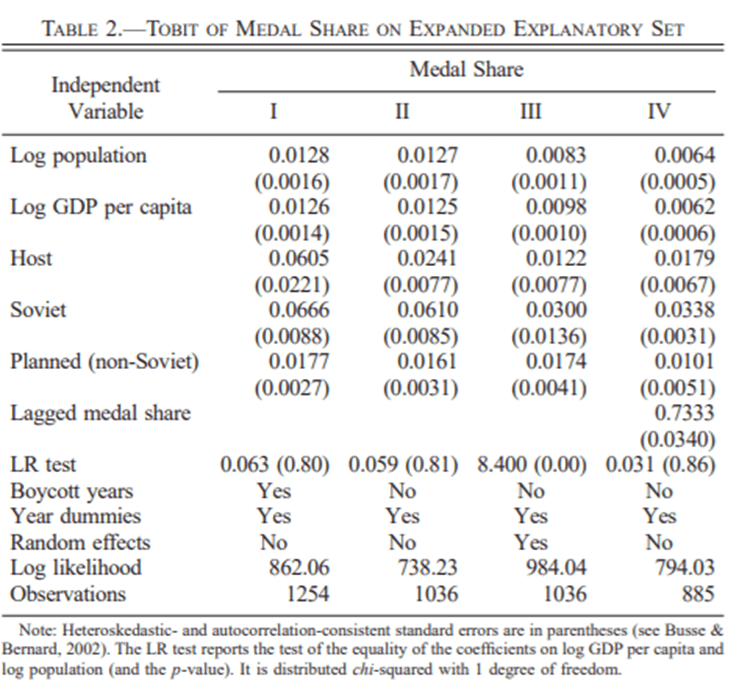

What about A? Normally, A is a scalar we use in a Cobb-Douglas function to illustrate the effect of technological progress. However, it is also frequently used in the economic growth literature as the stand-in for the quality of institutions. And if you look at Bernard and Musse’s article, you can see institutions. Do you notice the row for Soviet? Why would being a soviet country matter? The answer is that we know that the USSR and other communist countries invested considerable resources in winning medals as a propaganda tool for the regimes. The variable Soviet represents the role of institution.

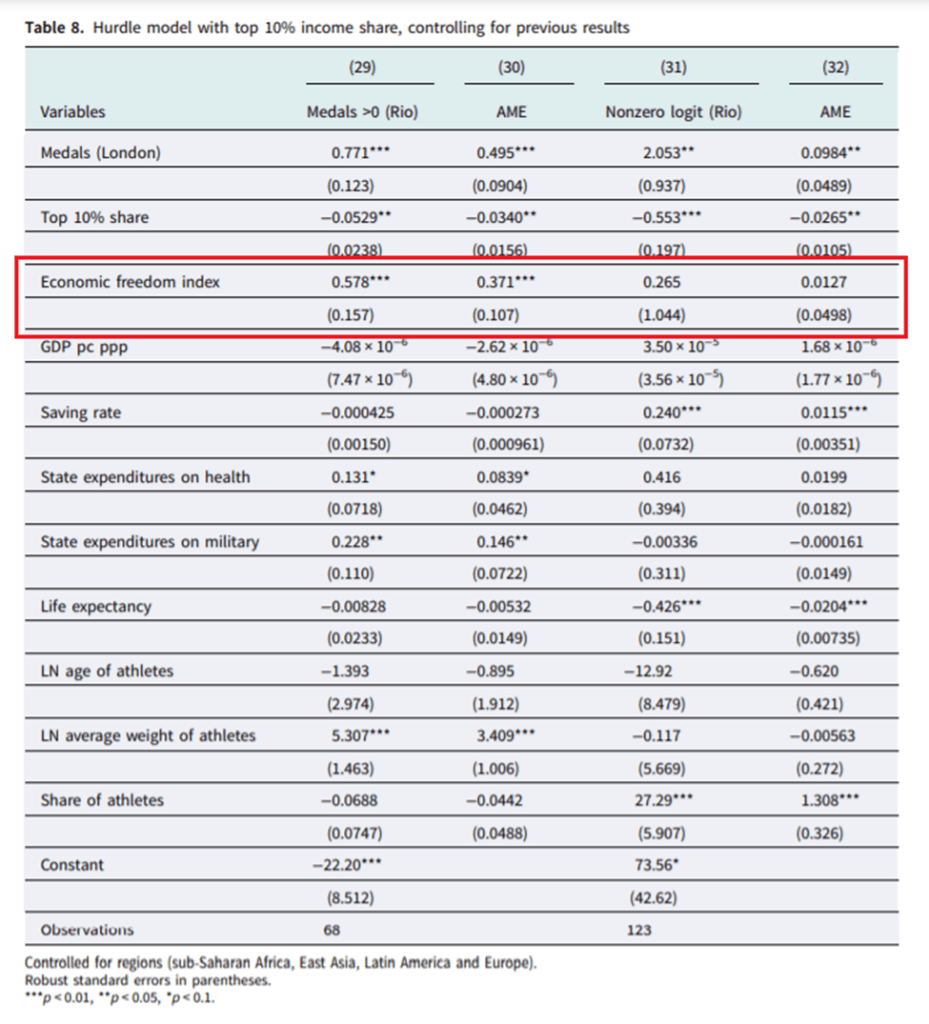

And this is where the political economist has lots to say. Consider the decision to invest in developing your skills. It is an investment with a long maturity period. Athletes train for at least 5-10 years in order to even enter the Olympics. Some athletes have been training since they were young teenagers. Not only is it an investment with a long maturity period, but it pays little if you do not win a medal. I know a few former Olympic athletes from Canada who occupy positions whose prestige-level and income-level that are not statistically different from those of the average Canadian. It is only the athletes who won medals who get the advertising contracts, the sponsorships, the talking gigs, the conference tours, and the free gift bags (people tend to dismiss them, but they are often worth thousands of dollars). This long-maturity and high-variance in returns is a deterrent from investing in Olympics.

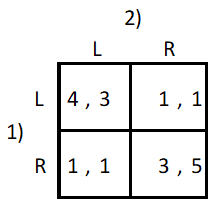

At the margin, insecurity in property rights heighten the deterrent effect. Indeed, why invest when your property rights are not secured? Why invest if a ruler can take the revenues of your investment or if he can tax it to level punitive enough to deter you? In a paper published in Journal of Institutional Economics with my friend Vadim Kufenko, I found that economic freedom was a strong determinant of medal count. Vadim and I argued that secure property rights – one of the components of economic freedom indexes – made it easier for athletes to secure the gains of their efforts (see table below).

Two other papers, one by Christian Pierdzioch and Eike Emrich and the other by Lindsay Campbell, Franklin Mixon Jr. and Charles Sawyer, also find that institutional quality has a large effect on medal counts won by countries. Another article, this time by Franklin Mixon and Richard Cebula in the Journal of Sports Economics, also argues that the effective property rights regime in place for athletes creates incentives that essentially increase the supply of investment in developing athletic skills. The overall conclusion is the same: Olympics medal counts depends in large part in the quality of institutions in an athlete’s country of origin.

Phrased differently, the country that is most likely to win a ton of medals is the economically free, rich and populous one. That’s it!