Today marks the 27th anniversary of John Nash winning The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his contributions to game theory.

Opinions on game theory differ. To most of the public, it’s probably behind a shroud of mystery. To another set of the specialists, it is a natural offshoot of economics. And, finally a 3rd non-exclusive set find it silly and largely useless for real-world applications.

Regardless of the camp to which you claim membership, the Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium (PSNE) is often misunderstood by students. In short, the PSNE is the set of all player strategy combinations that would cause no player to want to engage in a different strategy. In lay terms, it’s the list of possible choices people can make and find no benefit to changing their mind.

In class, I emphasize to my students that a Nash Equilibrium assumes that a player can control only their own actions and not those of the other players. It takes the opposing player strategies as ‘given’.

This seems simple enough. But students often implicitly suppose that a PSNE does more legwork than it can do. Below is an example of an extensive form game that illustrates a common point of student confusion. There are 2 players who play sequentially. The meaning of the letters is unimportant. If it helps, imagine that you’re playing Mortal Kombat and that Player 1 can jump or crouch. Depending on which he chooses, Player 2 will choose uppercut, block, approach, or distance. Each of the numbers that are listed at the bottom reflect the payoffs for each player that occur with each strategy combination.

Again, a PSNE is any combination of player strategies from which no player wants to deviate, given the strategies of the other players.

Students will often proceed with the following logic:

- Player 2 would choose B over U because 3>2.

- Player 2 would choose A over D because 4>1.

- Player 1 is faced with earning 4 if he chooses J and 3 if he chooses C. So, the PSNE is that player 1 would choose J.

- Therefore, the PSNE set of strategies is (J,B).

While students are entirely reasonable in their thinking, what they are doing is not finding a PSNE. First of all, (J,B) doesn’t include all of the possible strategies – it omits the entire right side of the game. How can Player 1 know whether he should change his mind if he doesn’t know what Player 2 is doing? Bottom line: A PSNE requires that *all* strategy combinations are listed.

The mistaken student says ‘Fine’ and writes that the PSNE strategies are (J, BA) and that the payoff is (4,3)*. And it is true that they have found a PSNE. When asked why, they’ll often reiterate their logic that I enumerate above. But, their answer is woefully incomplete. In the logic above, they only identify what Player 2 would choose on the right side of the tree when Player 1 chose C. They entirely neglected whether Player 2 would be willing to choose A or D when Player 1 chooses J. Yes, it is true that neither Player 1 nor Player 2 wants to deviate from (J, BA). But it is also true that neither player wants to deviate from (J, BD). In either case the payoff is (4, 3).

This is where students get upset. “Why would Player 2 be willing to choose D?! That’s irrational. They’d never do that!” But the student is mistaken. Player 2 is willing to choose D – just not when Player 1 chooses C. In other words, Player 2 is indifferent to A or D so long as Player 1 chooses J. In order for each player to decide whether they’d want to deviate strategies given what the other player is doing, we need to identify what the other player is doing! The bottom line: A PSNE requires that neither player wants to deviate given what the other player is doing – Not what the other player would do if one did choose to deviate.

What about when Player 1 chooses C? Then, Player 2 would choose A because 4 is a better payoff than 1. Player 2 doesn’t care whether he chooses U or B because (C, UA) and (C, BA) both provide him the same payoff of 4. We might be tempted to believe that both are PSNE. But they’re not! It’s correct that Player 2 wouldn’t deviate from (C, BA) to become better off. But we must also consider Player 1. Given (C, UA), Player 1 won’t switch to J because his payoff would be 1 rather than 3. Given (C, BA), Player 1 would absolutely deviate from C to J in order to earn 4 rather than 3. So, (C, UA) is a PSNE and (C, BA) is not. The bottom line: Both players must have no incentive to deviate strategies in a PSNE.

There are reasons that game theory as a discipline developed beyond the idea of Nash Equilibria and Pure Strategy Nash Equilibria. Simple PSNE identify possible equilibria, but don’t narrow it down from there. PSNE are strong in that they identify the possible equilibria and firmly exclude several other possible strategy combinations and outcomes. But PSNE are weak insofar as they identify equilibria that may not be particularly likely or believable. With PSNE alone, we are left with an uneasy feeling that we are identifying too many possible strategies that we don’t quite think are relevant to real life.

These features motivated the later development of Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibria (SGPNE). Students have a good intuition that something feels not quite right about PSNE. Students anticipate SGPNE as a concept that they think is better at predicting reality. But, in so doing, they try to mistakenly attribute too much to PSNE. They want it to tell them which strategies the players would choose. They’re frustrated that it only tells them when players won’t change their mind.

Regardless of whether you get frustrated by game theory, be sure to have a drink and make toast to John Nash.

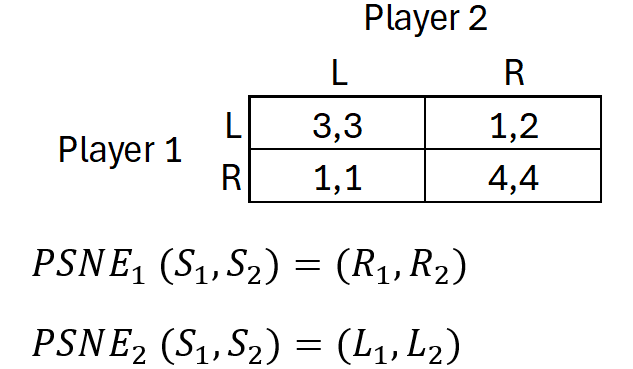

*Below is the normal form for anyone who is interested.