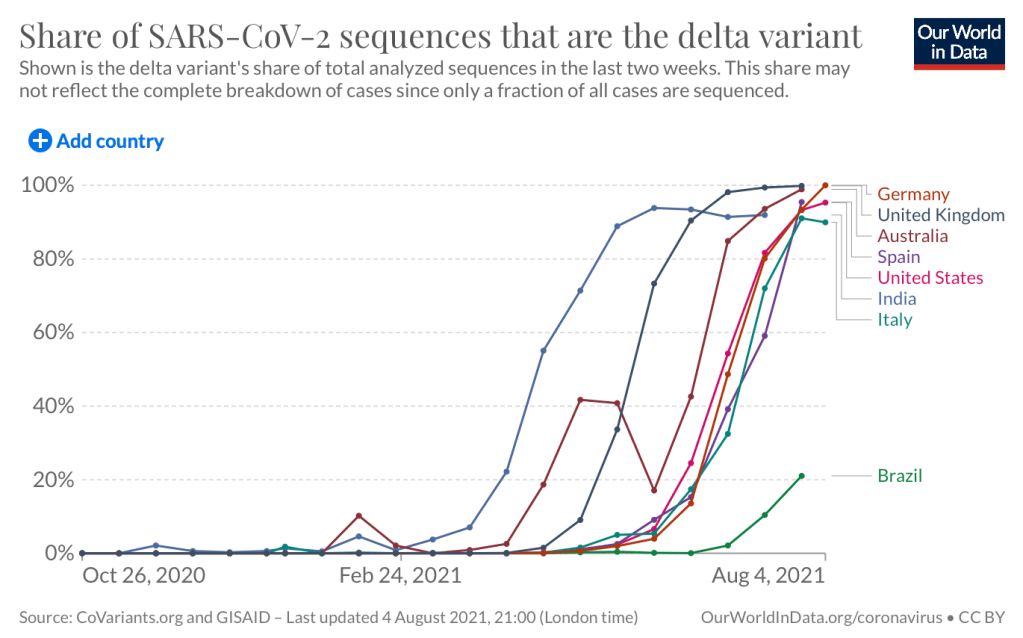

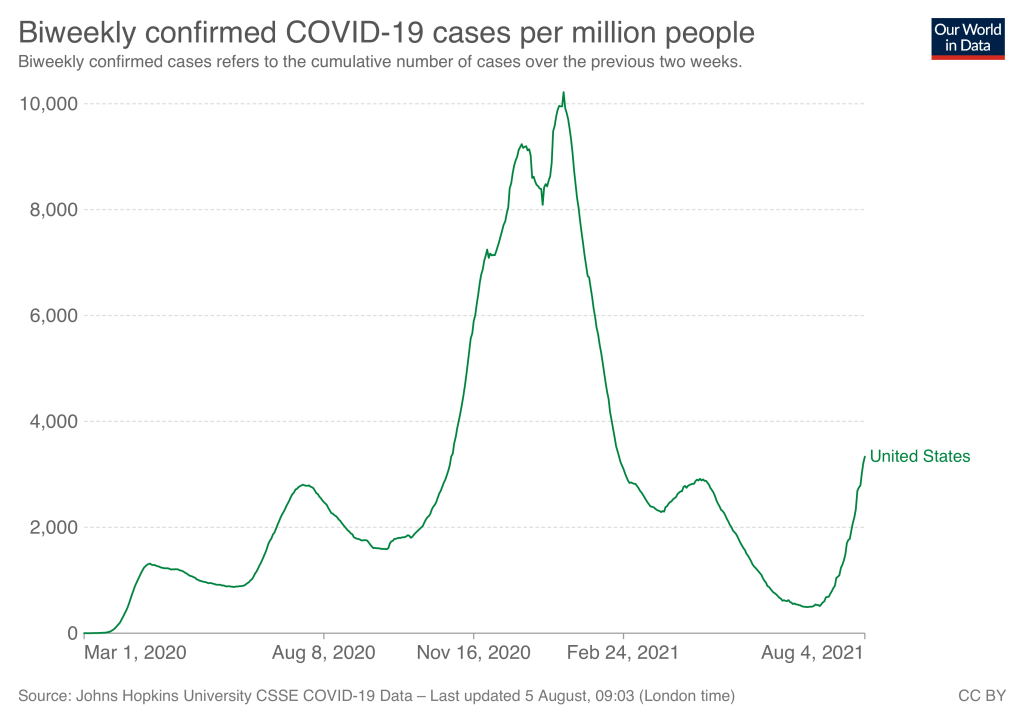

Two weeks ago I predicted that Covid cases would continue to spike for at least two weeks due to the Delta variant, but argued against general shutdowns as a way to combat this spike. Two weeks later cases have indeed spiked, and while localities and organizations have been mandating masks and vaccines, we have largely avoided new lockdowns, at least in the US (Australia is reverting to its roots as a prison). In the last post I mostly said what we shouldn’t do to fight Delta, so today I want to show what a better response looks like.

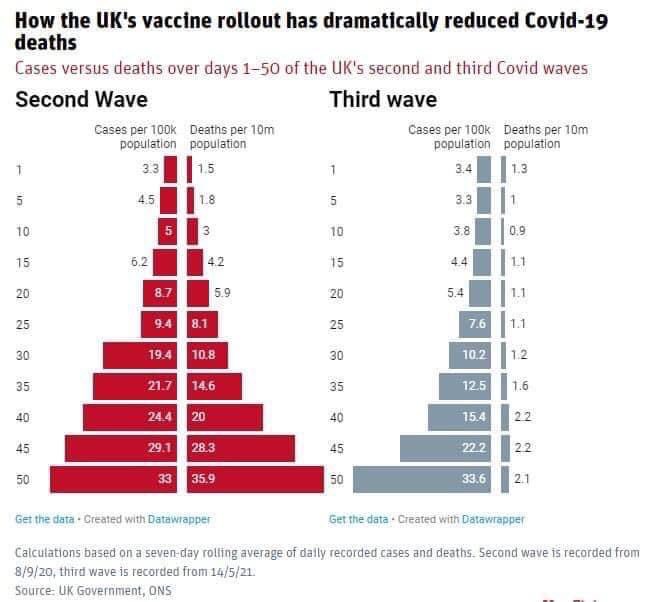

The tendency of authorities to reach first for coercive solutions is a natural product of their incentives, but I’ve been disappointed to see the same tendency among the chattering classes. I think this is due to polarization- people are most interested in debating solutions that are identified with a specific side in politics or the culture war. Masks became blue-coded, so many reds oppose them even though they probably work. Likewise with vaccines, even though they definitely work well and funding them early was the greatest achievement of the Trump presidency. Meanwhile certain medications became red-coded, leading blues to oppose them before the evidence even came in. But many of the best non-coercive and anti-coercive solutions barely get discussed because they have no political valence, or a mixed one.

Fully Approve the Vaccines Already!

The Covid vaccines are still being distributed under an emergency use authorization. This lack of full approval is a source of vaccine hesitancy. More concretely, it also means that pharmaceutical companies aren’t allowed to advertize their vaccines, even though they are much more effective than the typical pharmaceutical you see advertized. The randomized control trials testing the vaccines have been complete for months, we are just waiting on the FDA to do their job.

Authorize Vaccines for Kids

The FDA still bans children under 12 from receiving the vaccine, saying they are waiting for more trial data. Last week, the American Academy of Pedicatrics argued that we have enough data to justify an Emergency Use Authorization for children aged 5-11 given, you know, the emergency. The government is going to make my 5 year old wear a mask to kindergarden won’t allow me (or my physician wife!) to get him a vaccine which would protect him and others much better than a mask.

Ventilation

Opening windows, modifying HVAC systems to bring in more outside air, and using air purifiers is about as effective as requiring masks and is definitely less of an imposition on people. But we don’t talk about it, partly because people took so long to recognize that Covid is spread through the air more than through droplets, and partly because it is less of an imposition on people and so never became a culture-war debate. Ventilation might be too boring to advocate but I think staying alive is very exciting.

Outpatient Treatments that Work

Repurposing existing drugs to fight Covid is a great idea that has not yet lived up to its promise, aside from the widespread use of Dexamethasone for inpatients with severe cases. The core problem is that it takes large randomized controled trials to really prove that a drug works, and these are expensive. Worse, pharmaceutical companies don’t want to pay for these expensive trials once their drug has gone off patent. This means that many promising treatments have been ignored, while a few have been over-promoted on the basis of observational studies and tiny RCTs (and worse, still promoted once large RCTs showed they probably don’t work). But the British government stepped up to fund the large trials that found Dexamethasone effective last year, and private donors have funded mid-size trials that just found Fluvoxamine reduced Covid hospitalization by 31%. This is excellent news because Fluvoxamine is a cheap and relatively safe anti-depressant that people can take at home. There are other promising treatments that have yet get funding for large RCTs; this is exactly the sort of thing that NIH should be throwing money at. While we’re waiting on compentent government, you can ask a doctor about outpatient treatment if you do get Covid.

Overall, many of our best tools for fighting Covid are being ignored despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that they maintain or increase our freedom.