- This is post coauthored with Jack Cavanaugh, Ave Maria University Graduate of 2025.

Say that you want to become a successful lawyer. What does that mean? One possible meaning is that you are well-compensated. Money is not everything, but it does give people more options for how to spend their time and resources. Law degrees are a type of graduate degree. So, what bachelor’s degree major should one choose in preparation for law school? We lack rich administrative data on college majors and LSAT scores.

Luckily, the 2023 American Community Survey (ACS) comes to the rescue. It has all of the typical demographic covariates, income, occupation, and college major. So, if we make the small leap that well-prepared law school students become high-performing lawyers who are ultimately paid more, then what college major puts you on the right path? What should your major be?

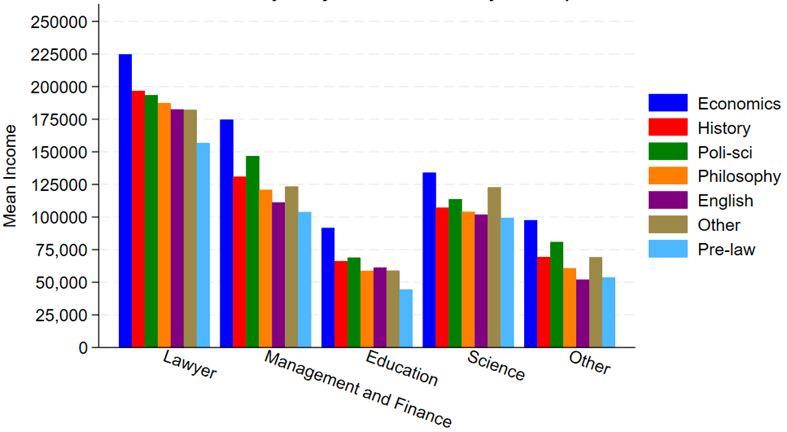

We don’t look at an exhaustive list. We place several occupations into bins and examine only a few alternative majors. Any unlisted major falls under ‘other’. Below are the raw average incomes by occupational category and college major. Note two majors in particular. First, Pre-law literally has the word ‘law’ in the name and is marketed as preparation for law school. However, it is the undergraduate major associated with the lowest paid lawyers. For that matter, Pre-law majors have the lowest pay no matter what their occupation is. Second, Economics majors are the most highly paid in all of the occupations.