An ex-co-worker was once complaining to me that the prices of things that he liked kept going up.

He was an economics major. Of course he knew that wages also increase. He wasn’t simply cantankerous about inflation. He knew all about improving productivity, income, and price level changes. He was being more specific. The *particular* items that *he* liked were getting more expensive. He was complaining about what, to everyone else, were relative price changes.

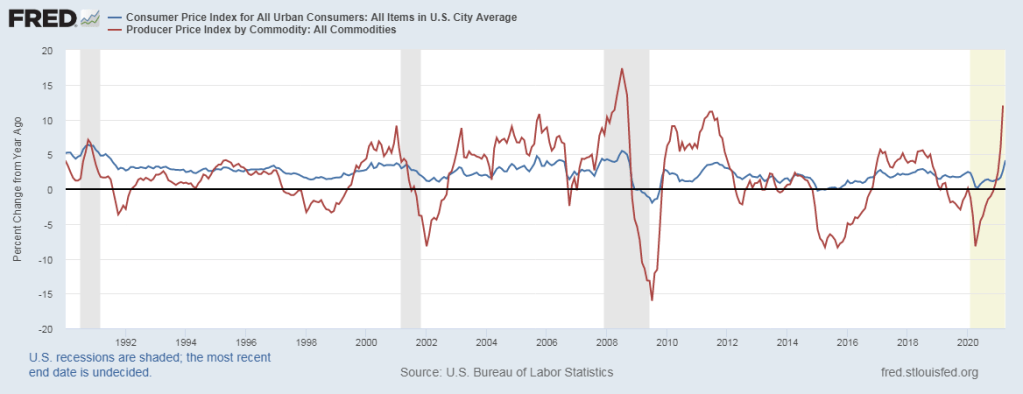

Unrelatedly, I was floating around the bls.gov website and examining their Producer Price Index (PPI) FAQs (I learned a bunch). The content is extensive. CPI is broken up into some subcategories. But PPI, being used by multiple industries and trade groups for real-life costs and benefits, is excitingly granular.

You want to know what happened to the price of red, white, rose, and carbonated wines each in particular? They’ve got you covered. It really is amazing.

Back to my co-worker. I tried to explain that relative price changes reflected underlying economic value and scarcities. We wasn’t having any of it. He just didn’t want his prices to go up. We economists are known for being kind of dispassionate. We see relative prices change and we shrug. Man-on-the-street sees a relative price change and, boy, does he care about it – if it’s the purchasing price that *he* faces.

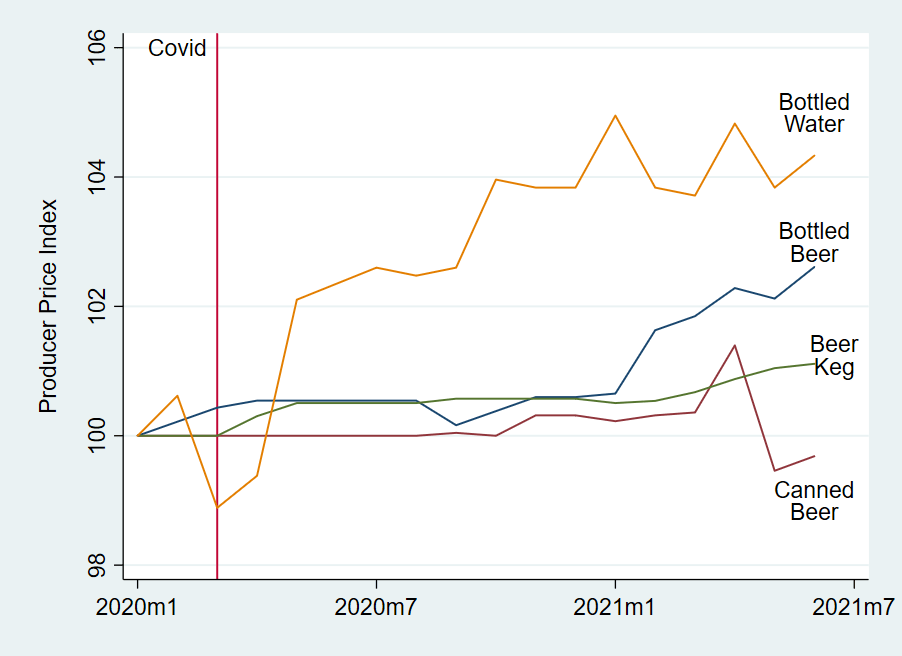

See the below graph. What kind of consumer are you? Since the start of the pandemic, canned, bottled, and kegged beer have all changed in price. Or maybe you’re a teetotaler and you’ve noticed the increasing price of bottled water. For interpretability, let’s consider what had cost $10 at the start of the year 2020. Bottled water has gone up to $10.50 and bottled beer has gone up to almost $10.30. You may not blink at a 3% price increase – unless it’s for 6 bottles of your favorite craft beer.

The price of canned beer, on the other hand, hardly increased at all. And in the last couple of months, the price *fell*. I sure hope that my co-worker is a canned-beer kind of guy. Otherwise, someone is sure to hear a lot of belly-aching.