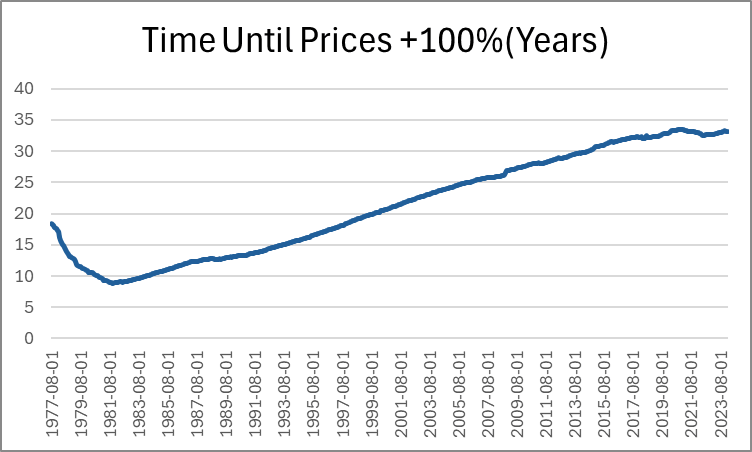

Last month, Jeremy wrote about how long it takes for prices to double. He identified a few intervals of time that are sensible. But I want to pick up the ball and move it further down the field. Not only can we identify how long it took for prices to double in particular eras, we can also do it for *every month*. Below, is a graph that shows us how many years had passed since prices were half as high (PCE Chained Prices).

Expectedly, the minimum time to double consumer prices was in the early 80s, taking just under 9 years for price to double. The prior decade included the highest inflation rates in the past 70 years. Since that time, the number of years needed in order for prices to double steadily rose as the average inflation rate fell. That is, until after the pandemic stimuli which caused the time to plateau. But to be clear, that must mean that prices aren’t doubling any fast that they used to, despite what we’ve heard on the news.

Except… prices are in fact rising faster by 21st century standards. Indeed, measuring the time that it took prices to double covers up a lot of variation. After all, The PCEPI was 15.19 in 1959 and is 122.3 now. That’s only enough difference for three doublings. But as we lower the threshold for price changes, we can see more of the price level patterns. Below-left is the time that was necessary for prices to increase by 50% and below-right is the time that was necessary for prices to rise by 25%.

In these graphs we can see more of the action that happened post-Covid. The time needed for prices to rise by 50% has fallen by about five years since 2020. That’s a 20% shorter time necessary for a 50% increase in prices. The time needed for a 25% increase in prices is even more drastic. As of 2020, people were accustomed to experiencing upwards of 14 years before overall prices rose by 25%. That number fell below 8 years by 2024.

And finally, the most unnerving graph of all is below: the time that was needed for prices to rise by 10%.

Continue reading