Here is a chart of the Core Personal Consumer Index for inflation (Core PCE), which is the Fed’s favorite measure on inflation, from 1970 through early 2024:

This chart is from an article by the Richmond Fed, The Origins of the 2 Percent Inflation Target. That article has a long discussion of how and why the Fed decided to name an explicit inflation target of 2% in 2012. Although controlling inflation has been formally part of the Fed’s “dual mandate” since the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977, it had traditionally not set a single numerical target. After years of discussions within the Fed, it was decided that the benefits of a clear single target outweighed the potential downsides. 2% was though to be about the lowest you could run, while still giving the Fed some room to cut short term rates in a recession without running up against the dreaded zero lower bound. It was understood that 2% was a loose target, with some years a little over or under to be allowed to balance each other out.

That Richmond Fed article was published in early 2024. At that point, inflation was falling quickly and steadily from its post-Covid high, as consumers finished spending down their gigantic stimulus package windfalls.

Unsurprisingly, this article concludes that “Even during this period, long-run inflation expectations have remained anchored, rising no higher than 2.5 percent, according to the Cleveland Fed.”

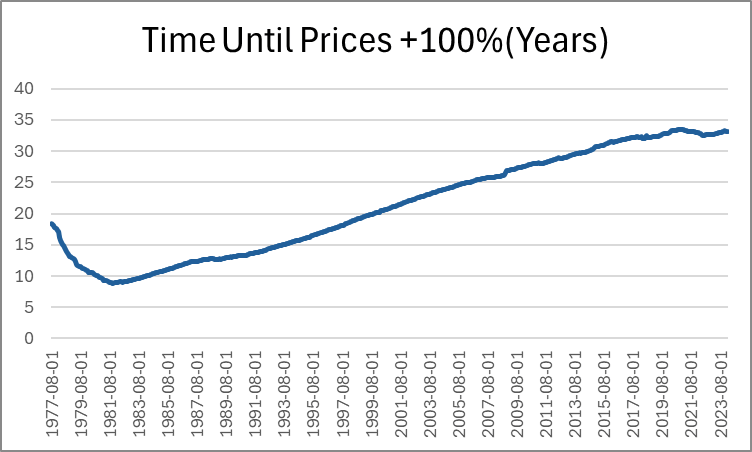

That was about 18 months ago. The actual path of inflation since then has not be a descent to 2-2.5%. Between gigantic peacetime deficits by two administrations, and the results of tariffs, inflation seems to have leveled out at around 3%:

The sub-2% inflation that was normal for twenty years (2000-2020) may now be a lost world. This puts the Fed in an awkward spot. Even ignoring the irresponsible squawking from some quarters of the government, it will not be an easy decision to keep cutting rates (to address soft employment) if inflation stays this high. The Fed’s mantra this time around is that the current inflation is just a transient response to tariffs and so can be largely discounted. But I recall similar verbiage in 2021, as the Fed dismissed the ramping inflation back then as merely a transitory effect of pandemic supply chain restrictions. They were wrong then, and I suspect it would be wrong now to be too complacent. The 1970s-80’s showed that once the inflation genie gets out of the bottle, it can be very costly to subdue it. Whether 2.0 % is still the right target, however, may be open to debate.