While some of the 2025 data is still coming in (such as GDP), we already have much of the core economic data to evaluate the year.

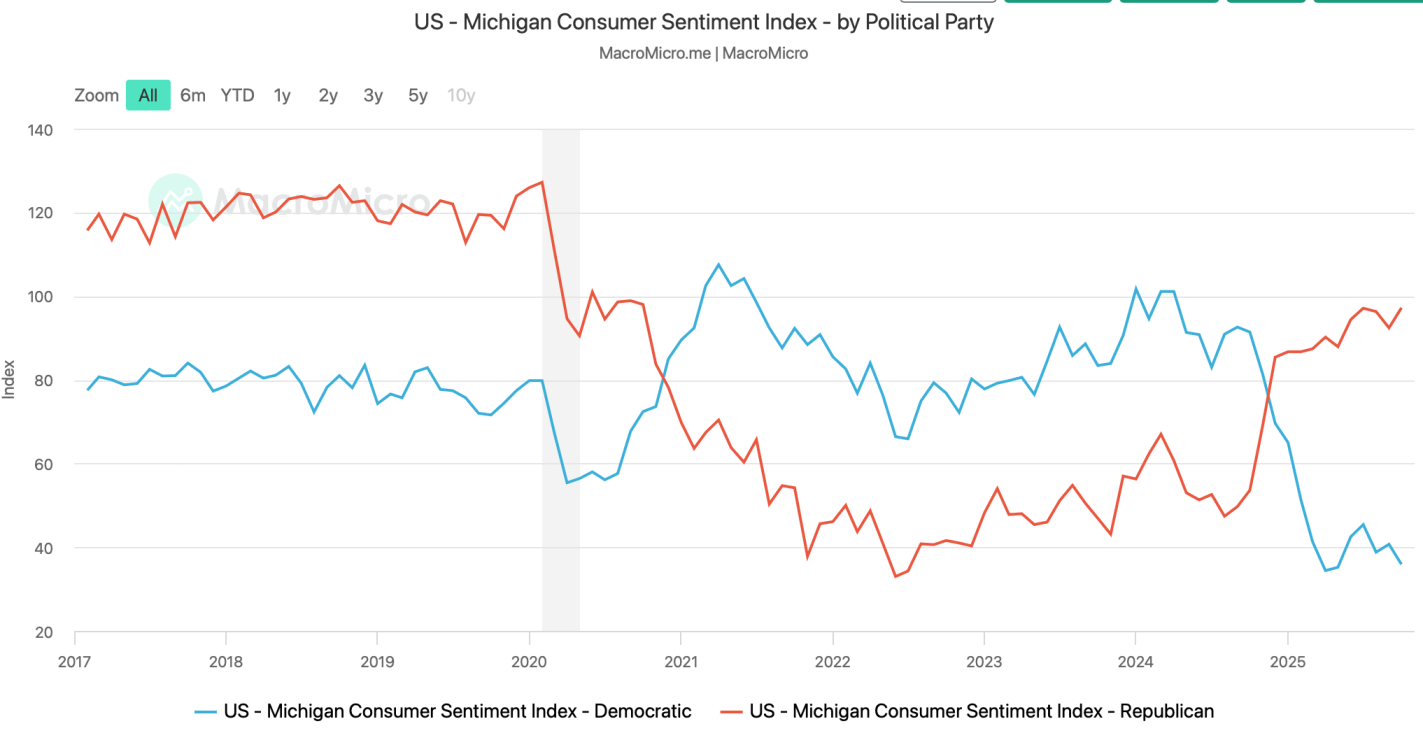

In a recent op-ed, President Trump claimed, “Just over one year ago, we were a ‘DEAD’ country. Now, we are the ‘HOTTEST’ country anywhere in the world!” Of course, every President claims they are doing great things, and Americans are almost exactly evenly divided over whether the economy was better under Biden or Trump — but this mostly just partisanism (Independents are close to evenly split, though).

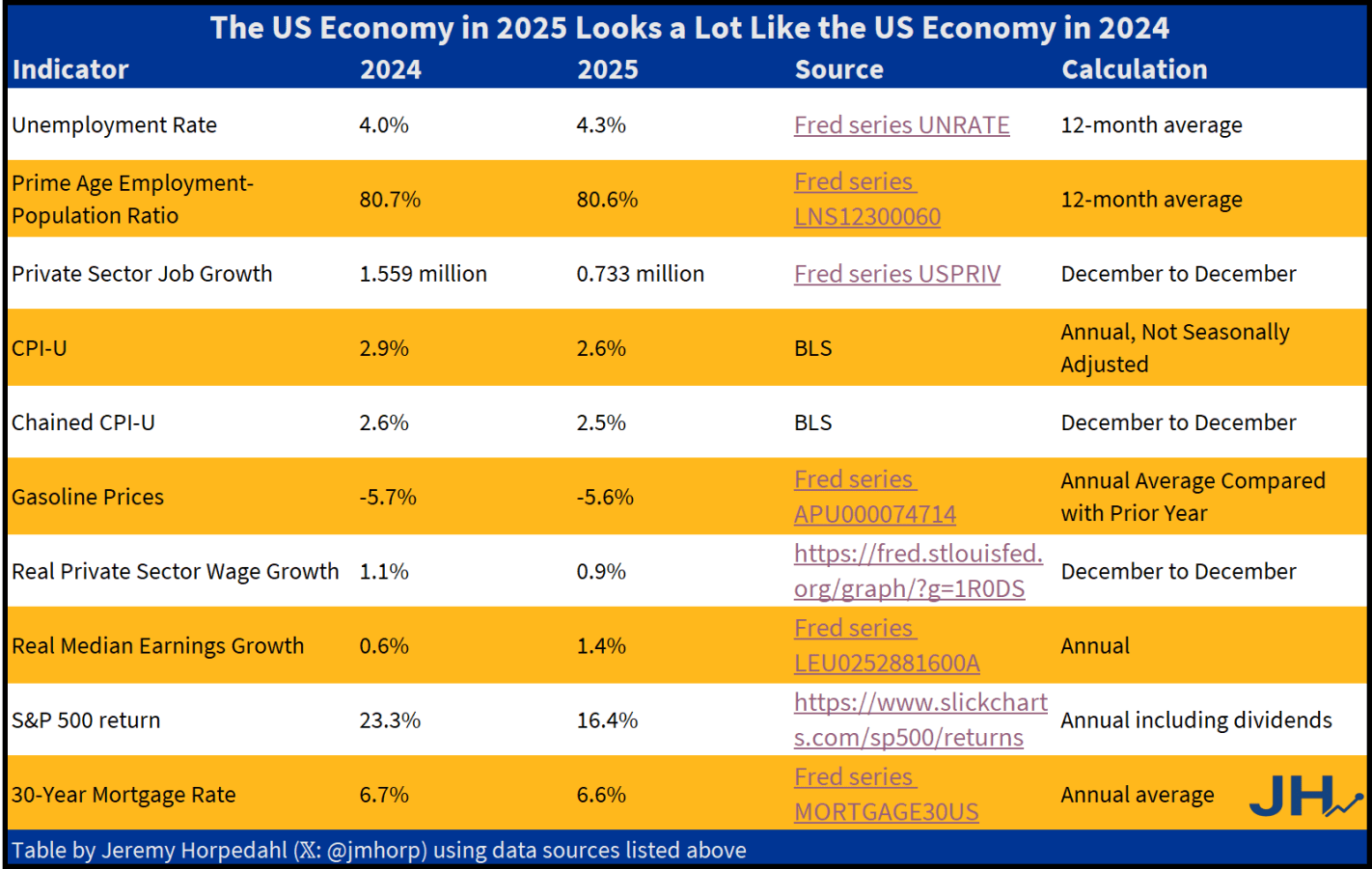

So what is the truth? I have put together what I think are the best economic indicators to judge how the economy is doing. And what does it tell us? I think the fairest read is that 2025 was a pretty good year, but based on most economic data it was almost identical to 2024.

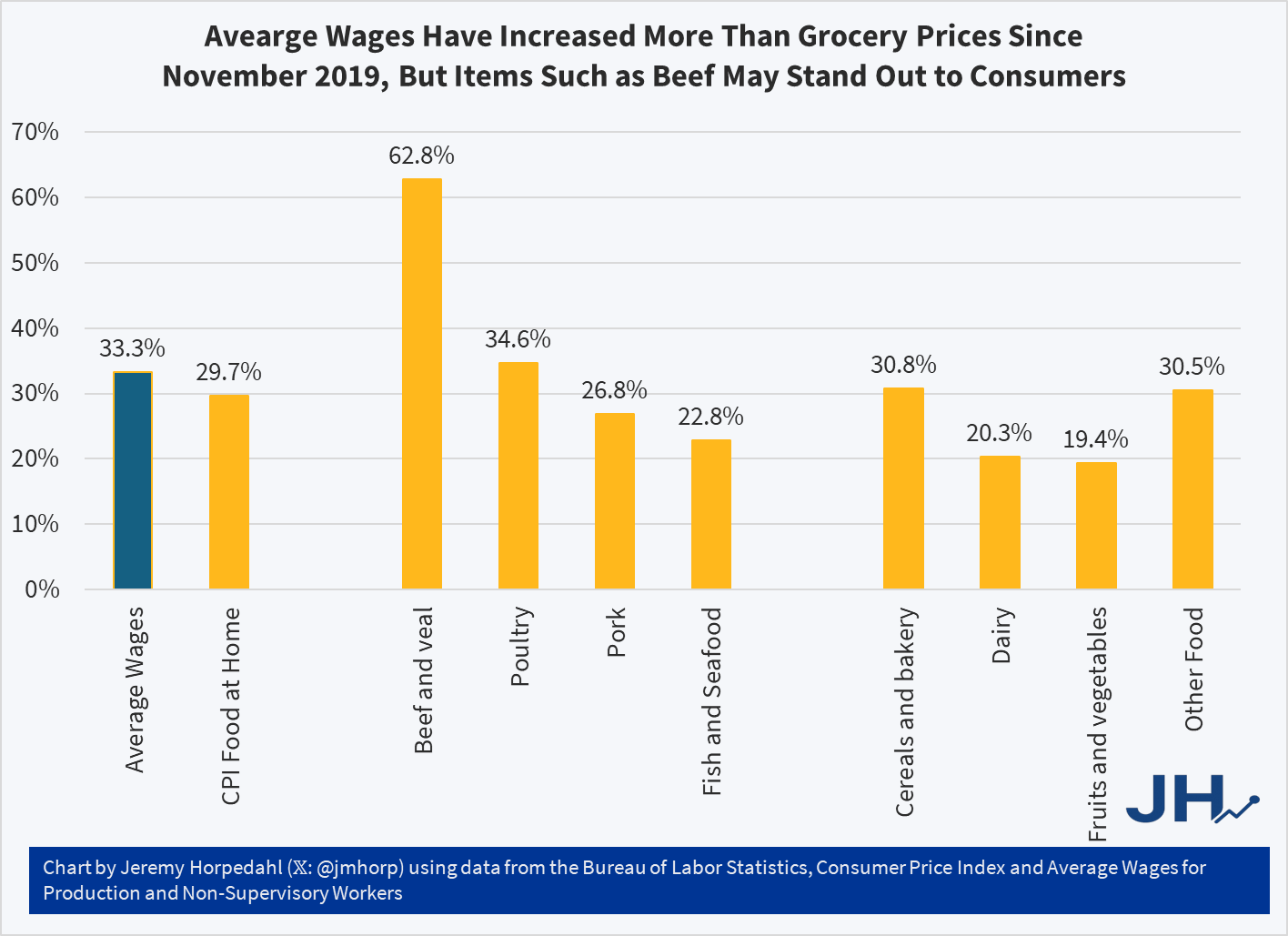

The only indicator that is clearly better is private-sector job growth in 2024. We might add S&P 500 in 2024 growth too, although some other assets such as gold have performed better in 2025. Inflation in 2025 is a tad lower, but not the massive improvement Trump suggests. This is especially the case for one of his favorite prices, gasoline. Yes, 2025 is a little lower than 2024… just like 2024 was a little lower than 2023.

And what of that greatest of all macroeconomic indicators, GDP? We don’t yet have Q4 data for GDP, which means we don’t have full-year 2025 data yet. But the growth rate of real GDP in 2024 was 2.8%, and betting markets are currently predicting 2.3% for 2025. Betting markets could be wrong! But it seems unlikely it would be much above 2.8% (those same betting markets only think there is a 4% chance it will be over 3.0%).

None of this is to say that the 2024 and 2025 economies are exactly the same. Certainly there is more uncertainty due to the shifting tariff policy, but on the other hand even with that uncertainty the economy is still performing fairly well. And my table above only includes economic outcomes, not any changes to government budgets, nor important social indicators such as crime. These are important too, but my focus in this post is only on the economic data.

It seems that in those surveys about whether the economy is better now or under Biden, it would be useful to offer an “about the same” option. Of course, in 2021-2022 inflation was much worse under Biden — but job growth was much better. A lot of this was baked in from the pandemic, 2020 monetary and fiscal stimulus, etc. Once we were back to a semi-normal economy in 2024, it was a decent year. Not blockbuster, but decent. So was 2025.