I’ve never gotten this much attention before. Which is to say, my writing receives a small sliver of attention on occasion, but that small sliver is nonetheless far more than I’ve received previously in my life. To put it in better context, I’ve had a couple posts and tweets go mini-viral, which by the standards of major pundits or celebrities amount to little more than a throwaway post, but by the standards of my life up until now they elicited tidal waves of attention.

It felt pretty good.

Those good feelings, though, morphed into something else within a couple days. First, there came the fear of saying something wrong while more people were paying attention. That fear of negative approbation is nothing new or special, but it was certainly heightened. What was more disconcerting, however, was how the anticipation of attention, or more importantly possible lack thereof, crept into the back of my mind as I sat down to write future posts and tweets.

Here’s a an interesting phenomona: once you have enough followers on twitter, the lack of likes/retweets on anything you write becomes recognizable as implicit disapproval. You know what you wrote was put in front of a couple thousand people and yet nearly none of them felt it warranted a tenth of a second click. It stings.

That sting from the absence of approbation changes the incentives in front of you, maybe for some even more than the initial serotonin-dump from previous bursts of positive attention. You feel the pull to write about the things that got attention before, to write in the same manner or mood. To give the customers what they want.

And the customer that matters most is the part of your brain that wants to re-live the thrill of thousands of strangers telling you that you are good and smart and pretty and are totally worth keeping around. This is an addiction. Now there is, of course, no shortage of people calling social media an addiction. What I would like to argue is that it is a particularly dangerous addiction because it is a perfectly rational addiction.

A Rational Addiction Model of Attention

I’ll skip any real math, but indulge me a moment of framing:

A simple model of rational addiction to attention starts with three inputs: positive approbation (P), negative approbation (N), and total attention (T), where T = P + N.

Now lets assume that your utility is increasing with P and decreasing with N, while also increasing with T. That’s all pretty uncontroversial for humans. Let’s also assume that negative attention is easier to reliably generate than positive attention (i.e. trolling is harder to ignore). To put a little structure on it, we’ll assume that they are all substitutes, but with different weights .

U = T^w1 + P^w2 – N^w3

What that means is that people have an incentive to pursue attention, but how they allocate their efforts across plays for positive and negative attention will depend on how much they weight the cost of negative attention relative to what they gain from total attention.

Here comes the twist, though.

What if T is not the absolute total attention you are receiving today, but instead T is the total attention you are receiving today relative to the average attention you have received in the past, the level of attention you have become accustomed to?

U = (T- T_mean)^w1 + P^w2 – N^w3

Well now you’re on a hedonic treadmill, but for attention instead of wealth or luxury. Your brain has grown used to a rush of serotonin from the attention of millions of strangers. You’re like an adrenaline junkie, but instead of jumping out airplanes you’re trolling public figures and latching on to “Twitter’s main character” everyday.

What’s interesting about this model of rational addiction, however, is how quickly you can find yourself pursuing negatiive attention. ostensibly producing negative utility (i.e. actively making yourself unhappy) by pursuing negative attention because the total cost of that negative attention to you is less than the even costlier option of no one paying attention at all. Would you log on to twitter everyday if if cost you a hundred dollars? You would if not logging on cost you ten thousand. Same thing for those who are rationally addicted. What started out as a positive reaction to a small number of well-received insights has created a utility monster trolling the world in a desperate plea for negative attention in the hopes that it will grant the slightest reprieve from the icy desperate loneliness inside that haunts my every moment.

I’m fine. Really. I’m making a point.

When we talk about the problems of social media for mental health, we tend to focus on bullying, dysmorphic self-images, and the creation of false standards of value. I think all of those problems are extremely real, but they also seem like things that can be addressed with policies, oversight, or cultural adaptation. What I want us to consider is that attention at this scale is something that is so baked into the construct of social media that problems emerge from perfectly rational engagement by otherwise well-intending people. I’ve previously tried to model the loneliness that can come with being extermely online, but this in some ways is actually deeper.

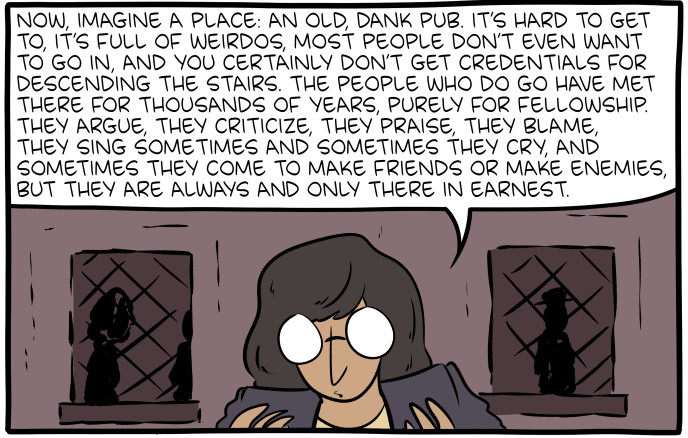

What if, for most of us, the only way to win at social media is not to play?