It’s spring break and that means catching up on both research and my social network. It also means college basketball. I remain firmly in the camp that college athletes should be paid for their incredibly high-value labor and, in turn, recapture a huge share of the surplus currently enjoyed by schools and coaches. What I am beginning to rethink, however, is the way that “professionalization” can and will play out.

This rethinking began with the the realization that my enjoyment of the product is largely insensitive to the presence of great players. The gap between NBA and NCAA basketball, in terms of quality of play, is so great that I simply don’t watch the sports in the same way. I consume the NBA the way I do Denis Villeneuve films: enjoying an artform in its closest approximation to perfection at the bleeding edge of innovation. NCAA basketball, in contrast, is a soap opera for genre aficionados. It’s Battlestar Galactica for sports fans.

There is a floating, ever-changing cast of characters supporting a handful of recurring leads. Clans and sub-clans. Rises and falls. Tragic failures and heroic redemption arcs. And, much like the latest show about wizards or post-apocaplyptic alien invasion survivors on the SciFy channel, the enjoyment of this product doesn’t require high level precision or execution. Quite frankly, the show is more enjoyable when the actors aren’t famous or especially elite; it keeps me squarely focused on the shlocky fun, rather than getting distracted by any urge to pick apart the film composition, story logic, or actor subtext. College basketball, in much the same way, keeps me squarely focused on the drama of gifted athletes doing their best to help their team achieve success in a limited window before moving on to the rest of their lives. Trying to get a little slice of glory now, while their knees will allow for greatness, before getting on with the endless particulars of adult life later.

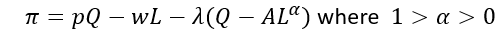

Which brings me back to the eventual professionalization of college sports with athlete compensation. Schools will find themselves faced with a decision of whether they should spend money on the very best athletes or try to compete with less expensive players. Athletes will have to decide where the best opportunities to develop their professional game are, and how much of their human capital investment portfolio they want to dedicate to sports. What might the equilibrium look like?

We can coarsely reduce the pool of athlete’s into three categories: all-in on athletics, those looking to purely subsidize secondary education, and those aiming for a mix of both. Currently schools capture the most rents from the pure athletics all-ins, who dedicate nothing but the bare minimum to schooling while maximizing their athletic preparation. The all-ins will often be the best players, who get the most media attention and contribute the most to winning glory, attracting applications from young fans and donations from nostalgic alumni. You might expect that compensation would shift the most suprlus to them. We have to consider, however, the possibility that a proper market for elite college athletic labor would provide the prices needed to accelerate the formation of pre-professional academies and player futures contracts. The very best 18-year old basketball players may find it far more lucrative to take a $120K in income and full-time coaching today in exchange for 2% of future professional earnings.

At the same time, college basketball may similarly learn the true nature of their collective good: that it is, in fact, a zero-sum competition where the total amount of talent isn’t nearly as important for earnings as they think. While a small number of schools absorbing all of the top talent might be exciting for covers of no longer existent sports magazines, in reality 120 teams competing for a less skewed distribution of talent more predominantly interested in subsidizing the full cost of college (i.e. tuition, lost wages, etc) may actually make for more drama, which means more ratings, which means more money. Why try to compete with the academies for 1 year of the next Lebron when those same resources, will get you 5 good players for 4 years? Combined with the fact that this bundle of athletes will place greater value on (nearly) marginally costless scholarships, teams looking to compete in the long-term with a maximimally effcient allocation of resources could shift the competitive equiibrium could actually shift away from the top talent.

Sports are fun when they are played at the highest level. They are also fun, however, when a little chaos is injected into the drama. It’s great when Steph Curry casually hits shots 40 feet from the basket, when Lebron James or Nikola Jokic make Matrix-esque passes through impossible angles. But it’s also great watching players struggle at the edge of far more human limitations to a find to win on the biggest stage of their lives while wearing the jersey of one of hundreds of colleges. The highest drama includes players making shots, but sometimes it needs players to dribble off their foot, too.

We don’t have to limit earnings to capture that glory. We don’t have to take money from young people whose particular talents put them in the sliver of the human population whose greatest earning potential might be age 20. We don’t need to appeal to platitudes or false nostalgia to explain why they’re being compensated with something better than money. We can just pay them. Some things will change, but I think you’ll be shocked to see how little the experience of college basketball will change. College sports will remain largely the same, but it will be a bit less shady, a bit less hypocritical. It will place greater value on, and care for, the players they have directly invested in.

Which, at least to me, would be a little more fun.