Raising kids is expensive. As an economist, we’re used to thinking about cost very broadly, including the opportunity cost of your time. Indeed, a post I wrote a few weeks ago focused on the fact that parents are spending more time with their kids than in decades past. But I want to focus on one aspect of the cost, which is what most “normal” people mean by “cost”: the financial cost.

Conveniently, the USDA has periodically put out reports that estimate the cost of raising a child. Their headline measure is for a middle-income, married couple with two children. Unfortunately the last report was issued in 2017, for a child born in 2015. And in the past 2 years, we know that the inflation picture has changed dramatically, so those old estimates may not necessarily reflect reality anymore. In fact, researchers at the Brookings Institution recently tried to update that 2015 data with the higher inflation we’ve experienced since 2020. In short, they assumed that from 2021 forward inflation will average 4% per year for the next decade (USDA assumed just over 2%).

Doing so, of course, will raise the nominal cost of raising a child. And that’s what their report shows: in nominal terms, the cost of raising a child born in 2015 will now be $310,605 through age 17, rather than $284,594 as the original report estimated. The original report also has a lower figure: $233,610. That’s the cost of raising that child in 2015 inflation-adjusted dollars.

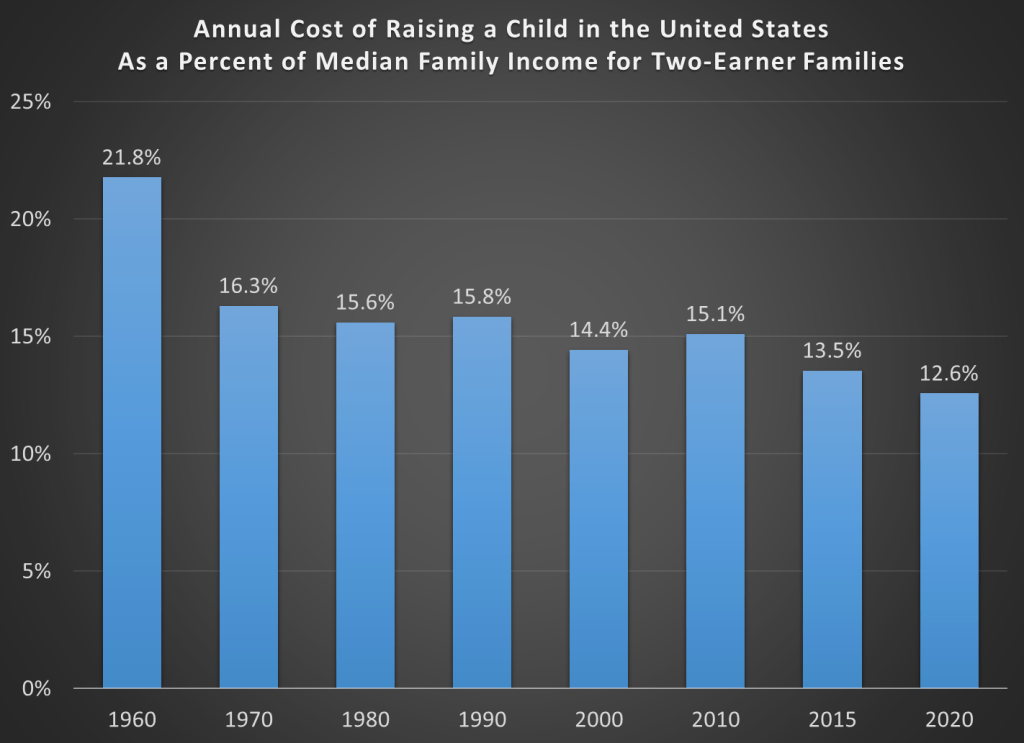

As I’ve written several times before on this blog, adjusting for inflation can be tricky. In fact, sometimes we don’t actually need to do it! To see if it is more or less expensive to raise a child than in the past, what we can do instead is compare to the cost to some measure of income. I will look at several measures of income and wages in this post, but let me start with the one I think is the best: median family income for a family with two earners. Why do I think this is best? Because the USDA and Brookings cost estimates are for married couples who are also paying for childcare. To me, this suggests a two-earner family is ideal (you may disagree, but please read on).

Here’s the data. Income figures come from Census. Child costs are from USDA reports in 1960-2015, and the Brookings update in 2020.